Kanche: Binding the un-bindable

Anirudh is a strong believer in the philosophy of “In the Fullness of Time”

Cinema is a compelling medium of communication, which can influence large audience. Looking back in history, we can look at numerous such instances where complex social, cultural, economic, political, psychological, and spiritual concepts were easily explained through cinema. Particularly in the Indian context, with the additional elements of “Bollywood-ness” in place, cinema becomes the sole source of entertainment and the major source of communication (wasn’t it quite evident with all the political movies during the election time?). Now that I have established the impact cinema has on people, I will take this opportunity to talk about one such movie, which stands out as one of my all-time favorites. Unlike the popular perception of how Telugu cinema is all about illogical fights, objectifying male gaze, and a lack of gripping story, a movie was made in the mid 2010s, which perfectly touches the most sensitive social issue and elaborates about it in the most cinematic way possible. Before going any further, I’d like to clarify that this piece is in no way a review of the movie, but is all about the common link between the Indian caste system, Freudian analysis of pain & pleasure and Shakespeare – all shown excellently through the film based in love.

“… A pair of star-cross’d lovers take their life;

Romeo & Juliet (William Shakespeare)

Whose misadventured piteous overthrows

Do with their death bury their parents’ strife.

The fearful passage of their death-mark’d love,

And the continuance of their parents’ rage,

Which, but their children’s end, naught could remove,…”

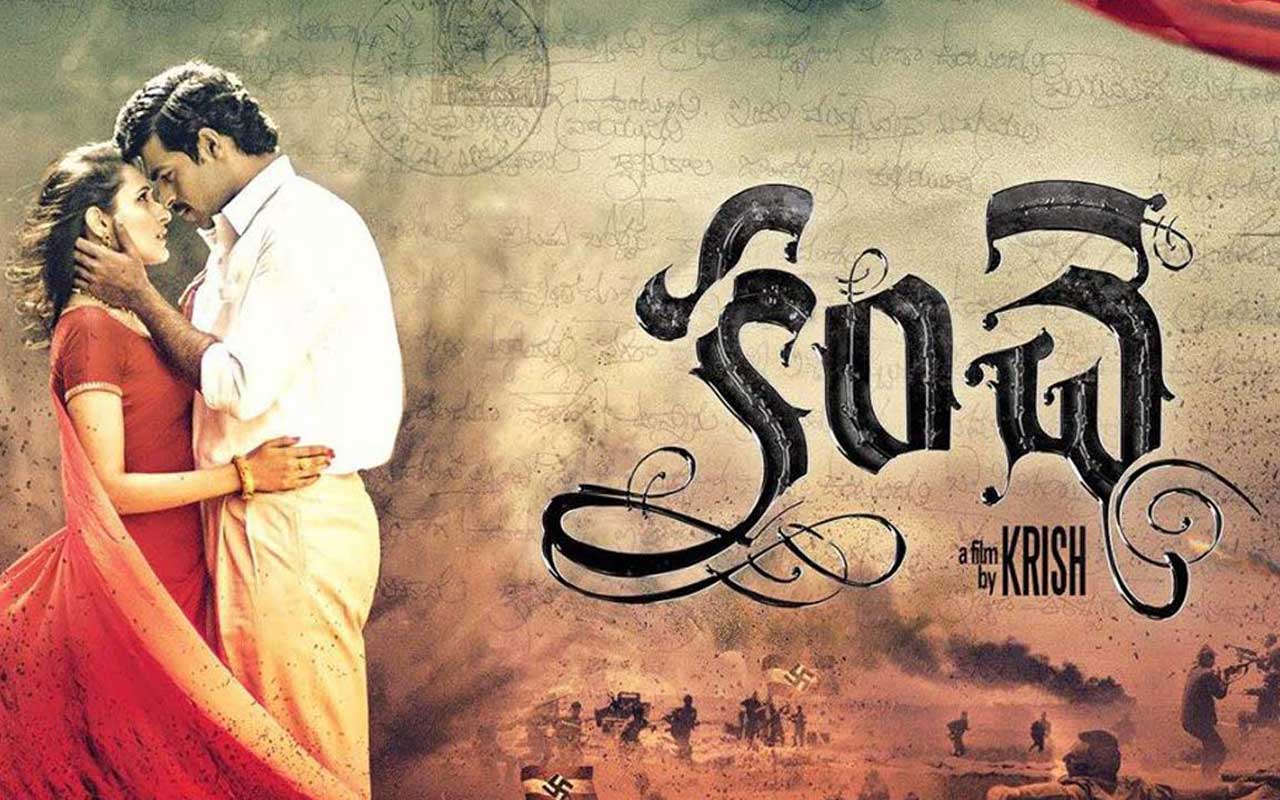

Kanche (translated as ‘fence’), a Telugu film directed by a national award-winning director Krish Jagarlamudi, perfectly sits with the above words from the most acclaimed William Shakespeare’s play Romeo & Juliet. Set during the colonial period of 1940s, the film presents the pressing social issue of caste, through a series of events that involve family, enmity, desire, power, knowledge, love, and finally, death. Historically speaking, we are well aware of the fact that Indians were forcefully sent to fight for the British in World War 2 (1939-45), making India indirectly a part of the war. This is the pretext used by the director in the film to talk about the most commonly encountered social issue – caste.

To give a context, the male and the female lead of the film are from the same village, where the female belongs to an upper-caste zamindari family, and the male belongs to a lower-caste dalit family. Under unforeseeable circumstances, both of them meet at their college in Chennai (erstwhile Madras) and unavoidably fall in love with each other in due course of their acquaintance. Here’s an interesting observation to be made. Looking at the way caste hierarchy functioned in India, we all know the amount of risk the male lead have taken by falling in love with the female lead in the film (given that he was well aware about her background throughout). As argued by Sigmund Freud in the Three Essays on Sexuality, on the one hand the predisposition of the human organism is to gain pleasure and avoid displeasure, and on the other hand, the disposition is towards self-destruction. The reason why I chose to call it “self-destruction” is because of the consensual choice made by the “lower-caste” male to fall in love with the “upper-caste” female.

To further complicate the plot (as love can never be simple), the story introduces a character of the female’s brother, who is an army officer working for the British Army in France. This man changes the plot from being a sweet romantic love story filled with love and pleasure, to a revengeful tragic story filled with hatred, anger and pain. As anticipated, he gets to know about the relationship of his sister with a lower-caste man and disapproves of the same. Starting with counseling his sister and convincing her to get out of the relationship, he goes on to abuse her and lock her up in their mansion, whose boundaries are covered by a boundary of fencing (hence the emphasis on how the literal fence is an indication of the social divide between both the “lovers”). This man questions the capabilities of the male lead and challenges him into a duel with him, during which the female lead gets stabbed accidentally and instantly dies (thus killing the only possible occurrence of a heterosexual relationship in the story).

To “move on” from this tragic incident, the male protagonist decides to join the army and fight against the Nazi army in France. As “karma” retaliates, the lead ends up in the team of the girl’s brother. The remaining movie goes on to portray the life of these soldiers in France, where they find similarities between the atrocities done by the upper-caste zamindars on the Dalits and Hitler-led Nazi army on the Jews. With a heated exchange of words and blows at different instances, the enmity between both the men develops into a pact, where they decide that if either of them dies, the other person takes the remains of the dead person to the village and mark the death as the message to unite the castes of the village.

Towards the end of the movie, the male lead gets shot by the Nazi army and instantly dies, trying to save the female’s brother. This makes the brother realize the importance of the sacrifice made by the male lead, and stands by his promise to take the remains of the protagonist to their native village. Back in the village, given the pact, the Kanche (fence) is brought down, thus signifying that the caste divide has been finally erased.

Now, analyzing the movie through a Freudian lens, we can understand that the entire dynamics of “pleasure” and “pain” operate hand-in-hand in the movie. It is repeatedly made evident that one phenomenon doesn’t mean existence without the obvious presence of the other. Throughout the film, phrases like “Love is like War” and “In War there is Love” are mentioned, signifying the interplay between love and war. As the movie depicts the interplay evidently, the male lead finds his place in a war-like situation because of his love towards his counterpart. Apart from that, it is also evident that the movie never tries to portray a heterosexual union of individuals. The main characters of the movie live with their respective grandparents, who are old to indulge into any sexual activities. The two lovers never get united, thus showing that their sexual relation is also not focused on. Further, the movie, like Romeo & Juliet, always involves the character of a female to be a battleground of conflict between two men. Both the men always indulge into heated exchanges either because of the female character present in the movie or because of a persistent presence of “male ego,” which is caused somehow or other because of the female lead.

The “fence” figuratively represents the caste-based separation of the families, and the importance of the same is highlighted towards the end of the film, where the fence that divides the “dalits” from the rest of the village is destroyed as a tribute to the death of the 2 “star-crossed lovers,” who sacrificed their love to unite the village. Using a similar analogy, this piece is named “Kanche: Binding the Unbindable,” signifying the unbindable nature of love, which is usually bound to certain social, political, economic, or psychological constraints in our daily lives. Love, which cannot be defined by absolute terms, is present everywhere. Can we truly bind it by whatever means we choose, let alone caste?

Featured Image Credits: Hungama

Readers' Reviews (3 replies)