Criminalizing Triple Talaq: Pro-women or Anti-Muslim?

Mohima Haque studied Political Science at the University of Hyderabad and Presidency University. She is an alumna of Sciences Po, Paris.

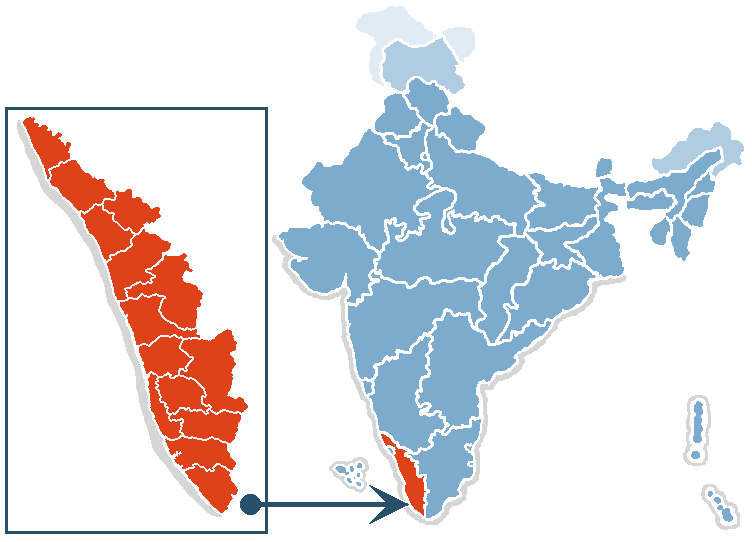

The usage of Triple Talaq has been a subject of long-standing debates. It was a form of Islamic divorce that allowed a husband to divorce their wife instantly at one sitting by saying ‘Talaq’ three times- either in spoken, written, or, more recently, electronic forms such as telephone, SMS, email, and social media. It was a practice prevalent among the Hanafi Sunni community but absent among the Shias. There have been various oppositions against Triple Talaq from Muslim women, organizations, and allied groups. Some of them filed PILs in the Supreme Court against the practice terming it discriminatory and regressive. It was finally in the 2017 Shayara Bano v. Union of India case that the Supreme Court declared instant Triple Talaq unconstitutional. It ruled any pronouncement of Triple Talaq by a Muslim husband upon his wife shall be null and void. The Parliament further passed the Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Marriage) Act 2019 criminalizing Triple Talaq, and making its practice a punishable offense with imprisonment for up to three years plus fine.

Introducing Intersectionality

While we discuss an issue like Triple Talaq, which emanates from the Muslim Personal Law (Sharia) and which affects Muslim women, the idea of ‘intersectionality’ becomes crucial. The term ‘intersectionality’ was coined by the US-based scholar Kimberle Crenshaw. It shows how identities such as gender, caste, class, race, religion, and ethnicity intersect and how these intersections come together to shape our experiences, life outcomes, and our oppression. Therefore, when we talk about Triple Talaq, it should be taken into consideration that while Muslim women belong to one oppressed category-women, they also belong to another marginalized community-Muslims. The intersection of two identities, namely women and Muslim, makes Triple Talaq a sensitive issue. This article tries to show how the newly enacted Act affects women in particular and the Muslim community in general.

Before going into further details, let’s have a brief look at the background of Triple Talaq. The civil life of Muslims in India is regulated by the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act 1937. Sharia is a body of Muslim Personal Law and draws from a variety of sources. The sources include the Quran (direct words of Allah), the Sunnah (teachings of Prophet Muhammad), qiyas (analogical and deductive reasoning), and ijma (consensus of Muslim jurists). It deals with civil matters like marriage, divorce, inheritance, and succession. Personal laws have been existing since the colonial period. The makers of the Indian Constitution agreed that alteration of personal laws and imposition of the Uniform Civil Code on Muslims would instill fear in a community that was already suffering from post-Partition trauma and insecurities. Personal laws were, therefore, left unaltered in the post-independence era. Triple Talaq falls under such personal laws of Muslims. Thus, the question arises if the Indian State can interfere in the personal laws of Muslims (here Triple Talaq).

The situation is further complicated by the fact that Muslims are an extremely vulnerable group in India, and interfering in their religion can mean alienating an already marginalized community. India is a secular country that gives the Right to Freedom of Religion to every person. It allows every person, including the minorities, to freely profess, practice, and propagate their religion (Article 25 of the Indian Constitution). Articles 29 and 30 of the Constitution also allow minorities to maintain and preserve their cultural, linguistic, and religious identity. The act of state interference in the personal laws of Muslims can mean depriving them of their Right to Freedom of Religion and diluting the secular credibility of India.

Principled Distance

However, the principle of state interference in religion does not necessarily go against the value of secularism, particularly when the practice in question is discriminatory. The Indian State didn’t adopt an official religion. Still, it also doesn’t follow the clear-cut wall of separation between state and religion. Instead, it follows what Rajeev Bhargava calls the policy of Principled Distance. It means the State neither mindlessly excludes all religions nor is blindly neutral towards them. It rather interferes with religions depending on the discriminatory nature of religious practices. It interferes more in religions where practices are discriminatory and maintains distance from religions where they are not, and thus, the distance is ‘principled’. The interference becomes important because most religions in India are discriminatory in nature and are insensitive to many of its members, particularly those at the bottom of the sanctioned hierarchy.

Triple Talaq was one such discriminatory practice. According to Sharia, Talaq is a form of divorce initiated by the husband to release his wife from marital ties. Divorce can also be initiated by wife (khula), mutual decision (mubaraa), and by courts (faskh). It is only when the divorce is initiated by the husband that it is called Talaq and this Talaq is the subject of our analysis. There are two types of Talaq in Islam: Talaq-e-Sunnat and Talaq-e-Biddat. Triple Talaq (Talaq-e-Biddat) was a deviation from the Quran-approved form of divorce: Talaq-e-Sunnat. While Talaq-e-Sunnat allows a husband to divorce his wife over a three-month period, thereby providing him the space to reconsider his decision and attempt reconciliation, Talaq-e-Biddat (Triple Talaq) was instant and irrevocable. Talaq-e-Sunnat requires a husband to divorce his wife by saying Talaq during the period of Tuhr (the gap between the wife’s two menstruations), followed by three months of Iddat. Iddat is a period which a wife observes after a divorce during which she may not remarry. Its primary purpose is to ascertain whether the wife is pregnant, and it is also the period when reconciliation is attempted. The husband can revoke the Talaq at any time before the completion of the three month Iddat period either expressly or through consummation, and marriage can be restored. It is only when the husband doesn’t revoke the divorce before the completion of the Iddat period that the divorce becomes final and the marriage is dissolved.

Talaq-e-Biddat, on the other hand, allowed a husband to divorce his wife instantly by uttering Talaq three times at one go. The divorce became irrevocable once Talaq was pronounced, and there was no scope for reconciliation. It finds no mention in the Quran and emerged in the second century at the hands of Umayyad Kings, who found the Quran approved formula of Talaq inconvenient and time-consuming. Talaq-e-Biddat gave arbitrary rights to Muslim husbands to break down a marriage whimsically and capriciously. The husband did not need to cite any cause for the divorce, and the wife need not have been present at the time of pronouncement. He could even pronounce Talaq via telephone, SMS, email, and social media. The husband monopolized the whole procedure of divorce without giving the wife any say in the process and was thus considered discriminatory towards women. It made Muslim women live with the mental insecurity that years of marital alliance can be ended by sudden, oral, and out-of-court utterance of three words.

The Indian Constitution is committed to the principles of equality and liberty. It, therefore, becomes imperative for the state to interfere in religion and modify discriminatory religious practices so that the principle of its commitment to equality and liberty is maintained. Article 25 (2) (b) provides that the State can change discriminatory religious practices to bring about social reforms. The interference of the State in banning the practice of Triple Talaq was, therefore, essential to ensure that Muslim women are protected against such discriminatory practices, and their equality and liberty are maintained. This move was considered emancipatory for the Muslim women, to liberate them from the shackles of patriarchy and capricious decisions of husband.

It is not to suggest that the Uniform Civil Code should be imposed. Muslim Personal Laws are essential to allow them to maintain their culture and identity in an otherwise Hindu majority country. What is suggested here is that the State should leave Muslim Personal Laws as it is, but it nevertheless should reform practices that go against the basic principles of equality, liberty, and social justice. However, the State shouldn’t decide this unilaterally. Instead, it should strive to reach a consensus after proper discussions with community representatives, legal experts, and other stakeholders. Triple Talaq has been banned in many Muslim-majority countries, including Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and India became the 23rd country to strike it down.

Discriminatory Legislation

While the Supreme Court’s decision to declare the practice of Triple Talaq unconstitutional was essential to empower Muslim women, the Union government’s move to criminalize it was certainly not. Marriage is a civil contract between two consenting adults, and its dissolution should also be civil. The decision to construe the practice of Triple Talaq as a criminal offense is rather vague. It also seems a little drastic to imprison a Muslim husband just for uttering three words.

The Act also makes the practice of Triple Talaq a cognizable and non-bailable offense. The offense is cognizable in the sense that the wife does not need to complain of the pronouncement of Triple Talaq by her husband. Instead, the police have powers to arrest a Muslim man on the accusation of Triple Talaq, without a warrant/court order, simply based on information received from any person related to the wife (by blood or marriage). It would provide mischief-makers the space to charge false accusations irrespective of the wife’s wishes. The offense is also non-bailable, meaning that the husband cannot get bail as a matter of right. He can be released on bail only at the discretion of the Magistrate, who, after receiving an application from the accused and hearing from the wife, must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for granting bail. The 2015 National Crimes Records Bureau’s prison statistics depicted that Muslims, Dalits, and Adivasis constitute 55% of all under-trials. The legal enforcement agencies are largely apprehended to be anti-lower castes, anti-minority at best. Given this grim ground reality, criminalization of Triple Talaq could become yet another weapon in the hands of partisan police to arbitrary put Muslim men behind bars. The Act would be open to misuse and make Muslim men easy targets of violations.

While the Act is undoubtedly anti-Muslim, it is also not pro-women. The Act doesn’t ensure the empowerment of Muslim women. It only adds to their misery and helplessness. The provisions of subsistence allowance and child custody are hogwash and don’t come in handy for women. A 3-year jail term will leave the husband without any source of income and cripple him financially. The Sachar Committee Report confirmed that the socio-economic conditions of Muslims are worse than any community groups in India, including the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. It is, therefore, not possible for an imprisoned Muslim husband to pay for the maintenance of his wife and children. Putting an errant husband behind the bar for three years will mean nothing less than an indirect punishment for the wife and children. The wife will be left with no resources to sustain her daily life, forget about resources to hire a lawyer to continue the legal battle for maintenance and custody.

Moreover, if a Muslim husband has to undergo prison terms for his wife, it is rather unlikely that when he returns home, he will take his wife back. The enraged husband may well resort to the approved form of divorce (Talaq-e-Sunnat) to pronounce Talaq over a three-month period, thus leaving the wife helpless. Sending a husband to prison can destroy a marriage rather than saving it. It would close all doors of reconciliation between husband and wife. Let’s not forget that the Muslim women who went to the Supreme Court against Triple Talaq wanted to save their marriage from hasty divorce and not to dissolve them.

The criminalization aspect would discourage women from taking the issue to court. It is well-known that the logic of stringent laws is flawed. They don’t stop offenses from taking place. Instead, what happens most of the time is that the accused kills their victim after committing the offence to eliminate evidence and avoid imprisonment. For example, in August 2019, a woman in Uttar Pradesh was burnt alive by her in-laws and husband after she went to the police because she was divorced by Triple Talaq. What Muslim women need is protection and maintenance, and the Act fails to provide both.

The BJP led NDA government, as argued by Flavia Agnes, wants to capitalize on the issue of Triple Talaq and project themselves-a Hindutva party-as the savior the Muslim women. However, as we go deep down, we realize it is just hogwash. Since the Act doesn’t do what it is supposed to do-protect Muslim women-it can be said that criminalizing Triple Talaq is nothing but a political move to attack the already marginalized Muslim community. While invalidating Triple Talaq was emancipatory for Muslim women, criminalizing it was certainly not. The Act is not pro-women, but it is anti-Muslim. It doesn’t provide protection to the women but adds to their misery and helplessness. Instead, what it does is to make Muslim men vulnerable and easy targets of violations. The draconian Act at best would only add to the insecurity and alienation of the Indian Muslim community as a whole, including women.

Insightful.