The pandemic of political uncertainty

Currently pursuing a Masters degree in Political Science from the University of Calcutta.

Pandemics in their occurrence leave behind harsh rudiments of truth. When the world debated on what was more injurious to international security, whether it was nuclear weapons, another world war, the gruesome oil-chase, or the disputes in the deep seas or in the invading borders; what one didn’t realize, is that major crises, do not blow trumpets when they occur; they arise through the most hideous of all places and rots the apple even before one knows it. The reason why pandemics shake the existent world order is that they come with the heavy baggage of uncertainty. While every form of media blares into the human mind locked within the four walls to embrace uncertainty with grace and patience, what one has to realize is that the world is yet again on the line eagerly waiting for the whistle to blow, to plunge relentlessly back into the ever-widening and interlocking world of globalization.

Nevertheless, what remains unnoticed is the fact that man craves certainty. Whether it is a man walking into a grocery store without a list or whether it is the supreme leader of a nation tackling an intangible enemy, uncertainty hampers thinking, socially, politically, and economically. The only reason why the connotations of uncertainty are distressing is that governments can lawfully contain the physical movement of individuals, but what slips out, is the ever thinking mind.

Uncertainty and its anathema

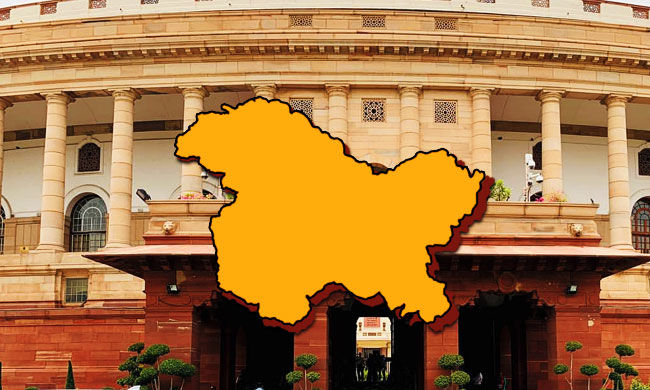

When Ingrid J. Haas of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and William A. Cunningham of the University of Toronto, worked on their research titled “The Uncertainty Paradox: Perceived Threat Moderates the Impact of Uncertainty on Political Tolerance”, brought to light the fact that uncertainty could invariably have implications on political tolerance. While political tolerance is extremely desirable for democracies like India, uncertainty may increase open-mindedness and information search for some while it may upsurge closed-mindedness and intolerance for the others. The research focused on how any attempt to threaten one’s survival and well-being during times of uncertainty will have aversive consequences, which is, although not justified yet, sadly unavoidable. In India, the Tablighi Jamaat in the crooked lanes of the country’s capital had hundreds of worshippers streaming in and out, which later turned out to become the potential epicenter of Covid-19 in the country.

What remained unquestionable was the fact that the event organized by the Tablighis did flout the norms laid out by the Delhi government and was indeed irresponsible. But what happens when Islamophobic tinted terminologies like #CoronaJihad and “corona terrorism” began to sweep through the internet? What happens when communalism mixes yet again with rationality and logic? What happens when in no time through the mediums of Whatsapp and television, 201 million Muslims in India became the most convenient scapegoat for the spread of a virus? “When people feel threatened, they often respond by becoming more confident in and more defensive of their prior beliefs, more closed-minded, and more aggressive toward those who don’t comply with them” as said by the above-named writers, leads the uncertain man into a cave of adopting a closed-minded, defensive stance.

It is this uncertainty that drives the Indian migrant worker to leave the capital and walk miles to reach his abode. It is this uncertainty that initiates a poor informal laborer incapable of paying rent and providing for one meal for his family, of escaping to where he finds familiarity and understanding. Arundhati Roy says in her article published by The Financial Times that, “they knew they were going home potentially to slow starvation…they knew they could be carrying the virus. And would affect their families, their parents, and grandparents back home, but they desperately need a shred of familiarity…if not love, as they walked, some were beaten brutally and humiliated by the police, who were charged with strictly enforcing the curfew”. She says that “our minds are still racing back and forth, longing for a return to ‘normality’, trying to stitch our future to our past and refusing to acknowledge the rupture. But the rupture exists.”

Politics during uncertainty

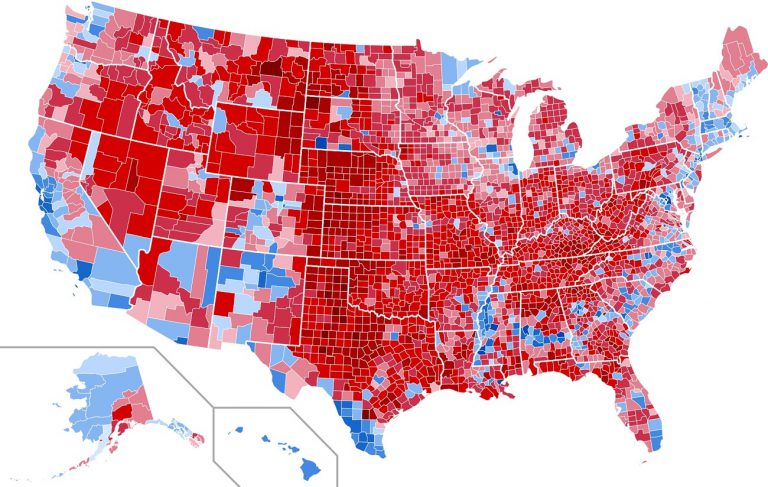

Today, Policymakers and political leaders are being lured into the debate of what uncertainties can be explored and whatnot, and politically charged decision making in these times, undeniably can be dubious and alarming. On 4th of April, 2020, the Indian Ministry of Commerce and Industry and the Directorate General of Foreign Trade, through a notification said, The export of Hydroxychloroquine and formulations made from Hydroxychloroquine, shall remain prohibited, without any exception, even though around 30 countries had requested India for the supply of the same, including the US. However, in a matter of not more than two days, US President Donald Trump urged India to provide the US with the supply of the said drug, or else there might be retaliation. The peculiar blend of intimidation and threat with the words of an apparently good friendship- “India does very well with the United States” like Trump said, caught the Indian regime logically concerned under the weight of uncertainty of the retaliations Trump could possibly mean. Uncertainty like in this case surprisingly shook the grounds of the one supplying the drug, by the one receiving it.

To date, no research body has clarified that the use of Hydroxychloroquine is effective in treating Covid-19 patients, and this remains as mere speculations; the conjectures whether India has enough Hydroxychloroquine for its domestic needs, is still not established and proven. The ability to forecast and predict decisions and foreign policy become imperative at such times. But how do governments tackle such times where certainty would be an element of the divine alone?

Uncertainty as opportunity

Luciano Floridi, in his work The Politics of Uncertainty, gives a very interesting view, he says that “uncertainty is preferable to ignorance.” This is definitely very true. When the world slowly recovers from Covid-19, global leaders will have to face the consequences of divergent criticisms, and the game of “they should have known better” will emerge again in political discussions. However, what a post COVID world has to realize is that boundless information in times where a vaccine to the virus appears to be a challenging task and normal lives seems to be distant and acutely compromised, uncertainty may be the biggest escape for the governments of the day. Floridi says that “John Rawls’ famous “veil of ignorance” is actually a “veil of uncertainty,” which exploits precisely the value of a lack of answers, to develop an impartial approach to justice in terms of fairness.” Similarly, in these times, where there exists an overload of information regarding ‘what has happened’ but the question of ‘what will happen’ remains disproportionately vacant and unanswered, the answers would lie in cautious policy-making and judicious political understanding devoid of partisan, religious, or ideological color.

Physicist, Richard P. Feynman once said that “It is in the admission of ignorance and the admission of uncertainty that there is a hope for the continuous motion of human beings in some direction that doesn’t get confined, permanently blocked, as it has so many times before in various periods in the history of man.” As long as a man keeps moving towards a cure, a vaccine, or a drug that successfully relieves the world of its high fever of lack of certainty and relieves man of the breathlessness of irresolute futures, till then the battle against the virus needs to be fearlessly fought by the ones ruling and also by the one’s being ruled.

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

Readers' Reviews (4 replies)