Education in post-colonial societies and Paulo Freire’s insights

Dr Jyoti teaches at the Department of Elementary Education, Gargi College, Delhi University. As part of her pedagogy, Dr Jyoti encourages her students to publish articles in the journal.

In this article, Professor Jyoti Raina and 4th-year student-teacher, Mansi, in the Department of Elementary Education, Gargi College, take an introductory look at the writing of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Though written half a century ago, his work has continued salience in contemporary India, as in other post-colonial societies.

A progressive pre-service teacher education programme does not necessarily educate student-teachers to fit into the existing school system. The prevailing school system of our society with its authoritarian structures, didactic pedagogy and increasing surveillance views education mainly as an acquisition of a given body of information. The Brazilian philosopher-educator Paulo Freire (1921-1997) critiqued such educational structures, systems and practices half a century ago specifically for these elements. He went as far as to reject such education and proposed his own radical conception of a critical education that was rooted in the life and aspirations of society from the perspective of the poorest people: peasants, manual workers and other rural folks. For him education did not mean simply learning the mechanics of reading, writing and arithmetic but an overall vision for society; intertwined with politics and social change. This necessitated seeing, hearing, questioning and discussing issues of agriculture, health, livelihood and ownership of factors of production. This meaning-making of reality, through the process of questioning and discussing, is central to Freire’s educational approach.

Freire proposes the concept of dialogue to formalise the educational processes of seeing, hearing, questioning and discussing. Dialogue involves twin elements of action and reflection in forming a pedagogic coalition between learners and teachers. He conceives of dialogue as a human phenomenon, an encounter between men devoid of the domination of one person by another. To him education is dialogue and dialogue itself is education as he writes,

Authentic education is not carried on by “A” for “B” or by “A” about “B”, but rather by “A” with “B”, mediated by the world- a world which impresses and challenges both parties, giving rise to views or opinions about it

Freire: 1970/1993:74

He was sceptical of bureaucratization in education as it turned people into ‘repeaters of clichés’ (Freire, 1978/2016:7) while annihilating criticality. It is easy to thus understand his distrust of formal institutions like schools and colleges. His work has salience in developing a critique of school education in any post-colonial society because of his general belief that ‘conventional schools enslaved and deadened the minds of children’ (Madan, 2020:159). His writings constitute a widely accepted intellectual strand in teacher education departments in global south societies. The conception of a forward-looking pre-service teacher education programme through the Freirean lens reveals what is wrong with prevailing educational practices. The critical social science framework for pre-service teacher education recognises the systemic failings; and attempts development of teacher agency to purge these in the direction of less exclusion, the inclusion of varied worldviews and egalitarian values.

Two of his best-known books that introduce the critical perspective to beginning student-teachers and are popular inclusions in the teacher education curriculum in India are his classic bestselling Pedagogy of the Oppressed and the powerful, accessible and easy-to-read Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau. His inspiration to write the first book was his aspiration to come up with a meaningful method to educate poor peasants in Brazil. The second book emerged from an exchange of letters with the Commissioner of State for Education and Culture, Republic of Guinea-Bissau; to develop a literacy programme for a newly liberated nation. This educational work was also connected to Freire’s attempts to transform the coloniser-inherited educational system of Guinea-Bissau. The two books present valuable analytical concepts like oppression, banking education, liberation, dialogue, problem-posing education, hope and critical pedagogy. These concepts have turned into keywords that have come to constitute almost a canon for the recovery of critical thought in teacher education.

Correspondence between social and educational inequality

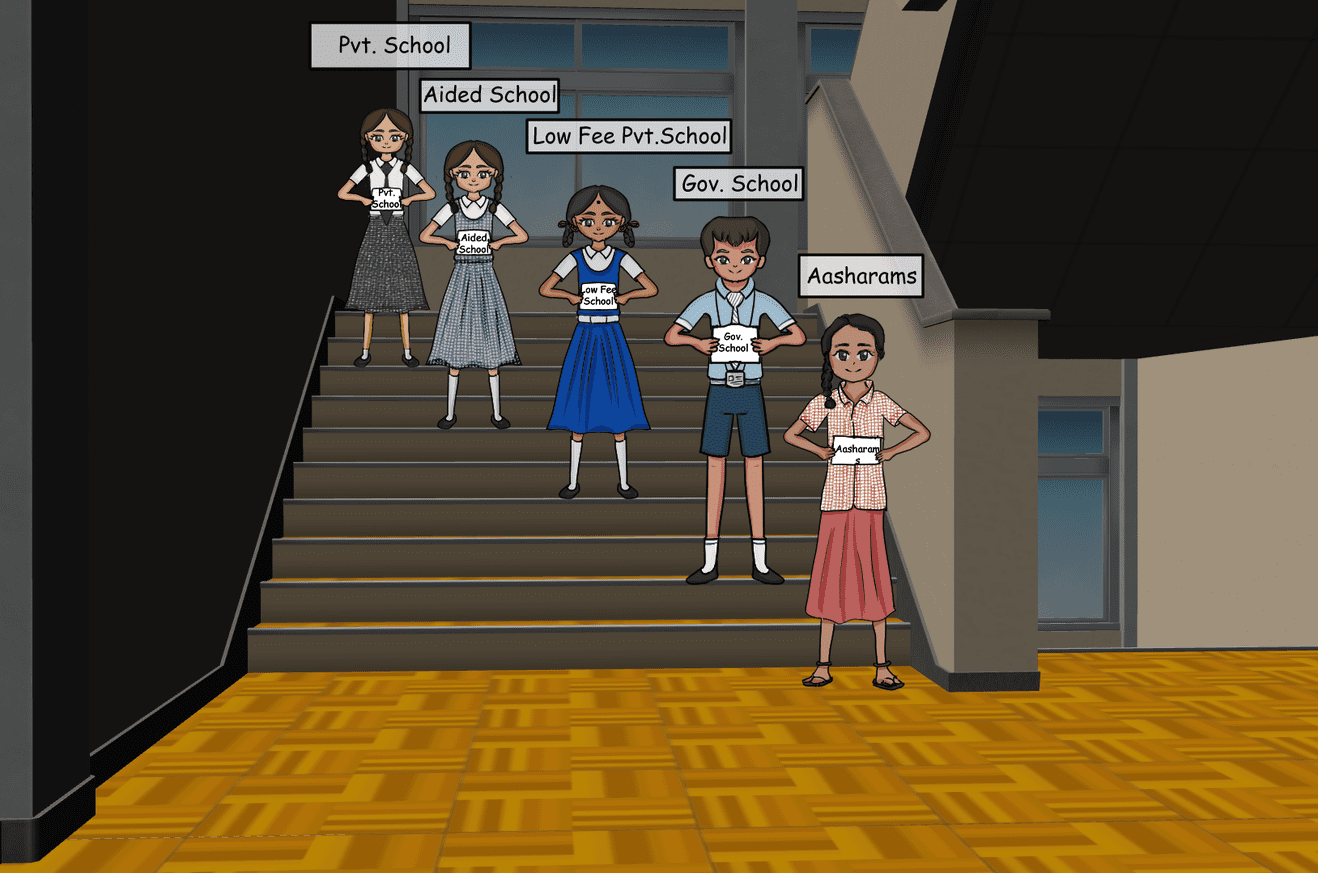

In India, the school system is not homogenous but consists of nine different types of schools in a differentiated hierarchy which also reflects social inequality (Vasavi, 2020). The government classification categorises schools into three types: government, aided and private but it is a social reality that schools are of nine different types. These range from Ashramshalas in tribal regions, government schools including those run by municipalities and panchayats, central government special schools like Navodaya and Kendriya Vidyalayas, low-fee private schools that are mushrooming in rural and urban areas, private schools, religious schools, alternative schools often run by NGO’s and international schools. Each social class in our multi-layered unequal society sends their children to one out of these types of schools, arranged in a graded hierarchy. Against the background of class differentiated multi-layered hierarchies of access of schools in India where the lower hierarchies of schooling access have become a colony of the marginalised; Friere’s vision of education which is based on forms of learning that liberate and empower the marginalized is resonant. His influence has shaped Dalit pedagogies, feminist approaches and participatory teaching methods that legitimise the worldviews of disadvantaged sections of society, in India as in other parts of the global south. These align with southern theories or southern epistemologies that are historical, contextually sensitive and extend to non-intellectual dimensions of human activity.

Colonial and postcolonial literacy and education programmes, in our country, have drawn from global north epistemes. These may be the reason for the failure of the state in educating our citizenry decades after independence, something to which Freireian educational methods offer a panacea. Apart from literacy programmes for adults, one of the celebrated applications of the Freirean method in India was the development of a visual approach to communication which was in turn used to effectively educate Indian communities. This was during an educational radio initiative in Bihar that wasn’t academic in the conventional sense but based on participatory photography with radio listeners. The listeners shared narratives accompanying photographs drawing upon their own life experiences during the course of this participatory communication related to the photographs. The organization of this participatory programme drew upon the Freirean concepts of dialogue, action and reflection upon the text, in this case, photographs. The listeners gained self-awareness as well as self-confidence in their own ideas that were previously ignored, rejected or simply not articulated in formal spaces like schools.

The Indian programme was aligned with another global south episteme: the concept of entertainment education, which has evolved from communication theory as a tool for promoting social change. A popular approach is the Sabido methodology which draws from the work of South American writer-producer Miguel Sabido. He was influenced by his contemporary psychologist Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory which argued that people learn whatever they observe. In 1975, he produced the Mexican soap opera Ven Conmigo (Come with Me) aimed at the social benefit of promoting adult literacy as he entertained the audience. The protagonists were adults enrolled in a literacy class. When one of the show’s episodes mentioned was made of a centre that provided free literacy booklets, 25,000 people came to the centre to get their own copy of the booklet the next day. The outcome of the entertainment education approach was community mobilization and action (Singhal et al, 2007). It is a testimony to the universal appeal of Freirean tenets in the global south that this project in India was inspired by a literacy project in Lima, Peru in 1973.

In the project, Freire and his associates raised the question, ‘What is exploitation?’. They asked ordinary people to answer by way of photographs. People submitted pictures of landlords, grocers and policemen among others but a child submitted a picture of a nail on a wall. This was bereft of meaning to the adults but evoked sense among many other children. During the dialogue, he learnt that the children were engaged in shoeshine work. Their customers did not live in the same community as them but in the city. Their boxes containing shoeshine materials were very heavy. The nails were the heaviest. To save themselves from lugging the weighty boxes, children hung the nails on a wall for the night before returning to work again. The Nail on the Wall photograph represented a form of exploitation in the name of work, and dialogue was critical pedagogy aimed at understanding and perhaps overcoming oppression.

Indian classrooms

Are Indian classrooms inclusive of knowledge systems and practices of the marginalised children? Do teachers attempt dialogues with their students to recover these epistemologies? Do our school systems provide space for it? Conventional classroom practices tend to be framed in terms of what Freire calls banking education during which teachers deposit a given body of information in the repository of students. They withdraw it from this repository and credit it into the examination account.

In the banking concept of education, knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider knowing nothing. Projecting an absolute ignorance onto others, a characteristic of ideological oppression negates education and knowledge as processes of inquiry

Freire: 1970/1993:53

An exploration of the spaces for Freirean dialogue inside and outside the classrooms of schools and colleges is a research-worthy idea. His concept of problem-posing education, as opposed to the banking method, enables both students and teachers to become living subjects of the educational process doing away with authoritarianism as well as alienating intellectualism. The problem-posing method begins with questions particularly those that interest the students. The point of beginning often is the very situation, ‘here and now’, whether it is agriculture, forestry, manual crafts or any other mode of production; which becomes the basis of the problem that is presented in the name of education. This ‘situation’, ‘problem’ or ‘interest’ then becomes the very object of children’s education, enabling the learners to become objective about the realities of their own life and develop knowledge during this process. It may even be possible to build upon it in the conventional intellectual or academic sense too, as Freire explains,

Problem posing education affirms men and women as beings in the process of becoming unfinished, uncompleted beings. In and with a likewise unfinished reality. Indeed, in contrast to other animals who are unfinished, but not historical, people know themselves to be unfinished; they are aware of their incompletion. In this incompletion and this awareness lie the very roots of education as an exclusively human manifestation

Ibid: 65

For a society such as ours, Freire’s theory and methods provide a conceptual framework, theoretical tools, moral compass and a vocabulary of both critique and possibility. In our unequal society, Freirean humanization is synonymous with a social justice orientation which eludes school education practices more than ever before at the current juncture of our educational trajectory.

References

- Freire, P. (1970/1993). Pedagogy of the oppressed. England: Penguin.

- Freire, P. (1978/2016). Pedagogy in Process: The Letters to Guinea-Bissau. London: Bloomsbury.

- Madan, A. (2022). Book Review Walter Omar Kohan, Paulo Freire: A Philosophical Biography (Jason Wozniak & Samuel D. Rocha, Trans.). London: Bloomsbury, 2021. 296 pages, INR 1742 (E-book). Contemporary Education Dialogue. 19(1), New Delhi: Sage.

- Singhal, A. Lynn Harter, Ketan Chitnis and Devendra Sharma (2007). ‘Participatory photography as theory, method and praxis: analyzing and entertainment- education project in India’, Critical Arts, 21, (1), 212- 27.

- Vasavi, A.R. (2019). ‘School Differentiation in India Reinforces Social’ Inequalities. The India Forum, https://www.theindiaforum.in/article/school-differentiation-india-reinforcing-inequalities

Decolonizing education is crucial for promoting inclusive and equitable societies. Freire’s insights offer a valuable framework for this process.This article underscores the need for education to be contextualized within local cultures and histories. A must-read for educators and policymakers.

Dr Jyoti Raina doing a great job. This article is well written and the design and representation are amazing. https://broomwiki.net

The article is written in a very thoughtful way. I am glad to read how much clarity you have regarding the pedagogy. The article makes me feel that you have such a clear view and insight and there is no room for doubt. The article is written in a very interesting manner and holds the reader till end. The analogy presented by you between the social context and educational strategies is remarkable.

The article is very well written and erudite. The ideas in article are critical to transformation of education. They capture my imagination as I am sure Paulo Friere must have captured imagination of his own country. The beauty of incompleteness in education touches the soul

Oppression is very well explained by Paulo and it has been beautifully brought here …. Yes there’s oppression in our education system and it’s high time we realise that and we start working on it. The article beautifully brings Paulo’s work and shows that it is still relevant in today’s world.

It is aptly describing the significance of Paulo Freire’s work in the field of education, even in today’s time. It has highlighted the major problem of the education system i.e. the Banking concept which has no scope for communication and makes education a very mechanical process.

It’s giving a beautiful insight of Paulo freire’s book as well as the current education system. The area of oppression is neglected or seen as “that’s how things should be” which needs to be changed.

Very well written article. It is describing the current situation of the education system clearly. Hoping that our education system also include ‘dialogue’ as a necessary element in organising the content of education for students.

Such an insightful article and the way it’s explained is extremely easy to understand