Samvaad- A lost art of dialogue and a need of the moment

Anuraag is a ‘Contributing Writer’ at the journal.

At the very outset, I would like to inform the reader that the piece is not an academic intellectual work. Neither is the author equipped enough to write academic articles on acclaimed or intellectually popular topics in contemporary news. The piece is a result of observation and self-realization, which has happened in the course of interaction with friends supporting different ideologies, professors, articles, and parents. The realization is, as the title suggests, the lost value of samvaad or conversation.

One must be wondering whether the author lives in a remote jungle or is a psychopath living alone in a dingy, creepy house. Else, why would he claim that conversation is lost unless not living in human society? Although we continue to converse right from mundane settings like asking for a cup of tea and knowing the well-being of our dear ones to addressing a gathering while in a conference or presentation, yet we have stopped indulging in samvaad or conversation of ideas. Here I would like to focus on the lack of dialogue between ideas and especially opposing views- an art and a legacy betrothed to us from ancient sages (rishis) and philosophers; an art which has disappeared and we have forgotten.

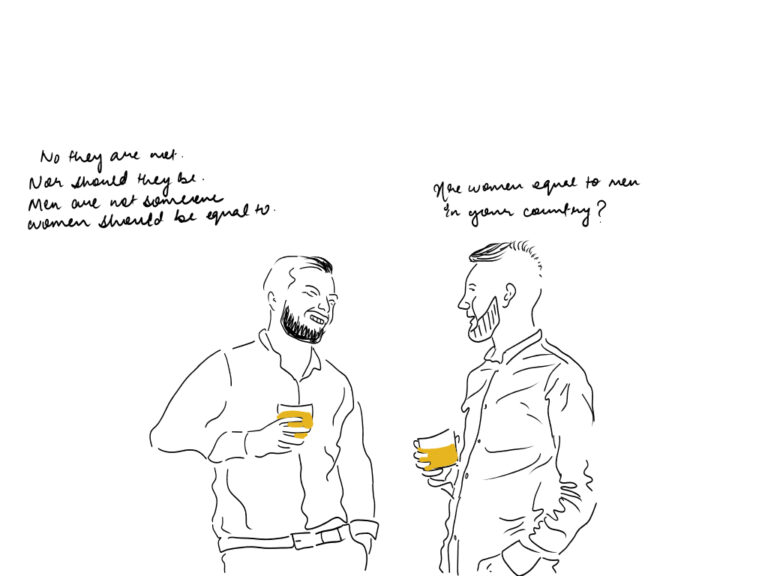

Today, if I may put so, we live and like to indulge in vivaad, whose rough English translation is disagreement and may extend to conflict. Although even philosophical debates and discussions since the Vedic era exhibit traces of disagreement or vivaad, yet generally, the participants had a sense of dignity and not to belittle the dissident view or insult the opponent (less of all, physically abuse him/her). Here I would like to point out one crucial feature of my version of samvaad– respect for the dignity of the dissident and the opposing view put forward by the latter. Vivaad, in the context of the present article, while including disagreements, also refers to the abuse (verbal and physical) of opponents and the refusal to hear the other viewpoint.

Our times

Coming to our current times, leave alone respect, sometimes the state hounds the dissidents (concerning mainstream and state-led viewpoints); the dissidents are also trolled with vitriol remarks on social media; labeled as ‘sickular, Congi, Bhakt, libtard; and most important anti-national’ etc. Public and television debates like to engage more in vivaad where the dissident speaker is not allowed to express his/her views and is instead labeled among the myriad titles mentioned above. And the degree of vivaad has gone to such an extent as to claim the lives of those expressing critical and dissenting viewpoints opposed to the popular, mainstream sentiment. We can observe this in the cold-blooded murders of Gauri Lankesh, Govind Pansare, M M Kalburgi, etc.

The specter of vivaad is not just limited to the state and its opposing viewpoints. It has plagued all of us and in our interactions with parents, relatives, and friends- given that they may hold diametrically opposite views. Instead of listening out to the opposing viewpoint, both sides at the slightest hint of dissent start labeling each other in mind as ‘Leftist, BJP Bhakt, Luddite, Modernist’ etc. This is then followed, in the Indian family context, of dissent by a younger member being labeled as ‘disrespectful of the elders (bado ki be-izzati); mannerless-ness (bat-tamizzi) or ‘ignorance’ (bewakoofi).

Similarly, the dissent by an elder is seen by the youngsters as ‘old-fashioned’ (puraane khayalat); ‘impractical and illogical’; boring (pakau), etc. No one is ready to listen and respect the other- countries (Indo-Pak, US-Iran, Israel-Palestine etc), religious groups, the party in power and opposition parties, politicians and JNU and other university students, mainland inhabitants and Kashmiris and North-Easterners, the Left and the Right ideologies, the old and the young generations etc. Often the opposing parties take pride in demolishing, ideologically and verbally, the other (vivaad) – whether in public debates, media shows, family conversations, etc.

Living in such conditions makes one feel the vacuum and the loss of the art of humane conversation marked by the acknowledgment and polite rebuttal of opposing views– the conversations between Maharishis Vasistha and Vishwamitra, Sufi and Bhakti saints, Tagore, Gandhi, Nehru, and Ambedkar, etc. While sometimes having diametrically opposing views, yet Vishwamitra never labelled Vasistha with any derogatory titles, nor in their interactions did Tagore, Gandhi, Dr Ambedkar and Nehru ever doubt the sincerity of their patriotism or use the label of ‘anti-national’ for expressing dissent.

In this, one can cite the interactions and correspondence between Gandhi, Ambedkar, and Nehru. While holding diametrically opposite views on caste and Hinduism in general, yet Gandhi and Dr. Ambedkar never threw personal insults at each other or called names while criticizing the vision of the other in speeches or public forums. Gandhi, on his part, even went to acknowledge Dr. Ambedkar’s expertise and competence in legal matters by recommending his inclusion in the Constituent Assembly; that too despite the latter’s staunch and harsh criticism of Gandhi in Reply to the Mahatma and What Congress and Gandhi Have Done To The Untouchables.

This was also true in the case of disagreement between Gandhi and Nehru on the idea of India’s post- Independence trajectory of development. While Gandhi wanted India’s progress, not on the lines of Western modernity and machine civilization, Nehru advocated for India’s rapid growth on the models of Western and especially Soviet industrialism – aptly covered by his remark ‘Dams are the temples of modern India.’ Despite these sharp differences in opinion, never did Nehru discard his reverence for ‘Bapu’ nor did Gandhi lose his love and affection for Jawaharlal, whom he often referred to as his son or heir to his legacy.

Samvaad between political ideologies

The conversations and interactions between such leaders should set an example as to how one can acknowledge and accept or critique opposing views without doubting or mocking the integrity of the rivals or attacking his dignity by name-calling. These are the kind of samvaad, which I believe has disappeared from the political and other discourses. At this point, I would like to emphasize the role of Gandhi concerning samvaad. One of my professors in university pointed out that the reason why Gandhi was and is currently derided by all forms of ideology (Hindutva, Left, Ambedkarite, etc) is because of his ability and willingness to have a samvaad with all forms of ideologies and acknowledge their opinions without abusing the proponents.

Gandhi’s line can substantiate this point in Hind Swaraj where he stated that his primary struggle is not against the Britishers but the modern, machine-oriented Western ideology which has immortalized the latter (Gandhi even states that the British themselves must be saved from the madness of modern civilization). Thus while critiquing the ills of British imperialism in India, Gandhi was acknowledging the presence and dominant view of his opponent (the British) and critiqued the ideology behind imperialism without necessarily abusing or insulting the British.

I believe Gandhi’s insistence on addressing the viewpoint of the dissenter and attacking it without de-humanizing or de-legitimizing the existence of the opponent, as seen in his interactions with the British, Dr. Ambedkar and Nehru should be the guiding point of our current conversations and debates. The state-led and mainstream discourse on nationalism should try to converse with the critique of nationalism based on the ideas of Einstein, Tagore, Andersen, etc. brought by the students and faculty of universities. Similarly, the mainstream Indian masses should at least try to have a sincere conversation with a Kashmiri or a Manipuri on their perceptions regarding governmental processes, the presence of the military, etc.

On the other hand, the Left and Ambedkarites need to re-engage in the samvaad with Gandhian thought on modernity, religion, caste, etc. and the same goes for Gandhians to acknowledge Dr. Ambedkar’s critique of Gandhi. At the level of family conversations and drawing from my personal experience, the often conservative elder taking the state and mainstream view should listen to and address the counter-points on nationalism, Leftist ideology, reservation, Kashmir issue, etc. by the dissenting youngster. The same is true for vice-versa when the modern, cool, and young lads and the elders of the family listen to each other’s views on ‘being modern’, social media, freedom, traditions, etc.

Talking it to the extremes

Interestingly I believe possibilities of samvaad could also exist between the above ideologies and the thoughts of Vinayak Damodar (Veer) Savarkar. Although known widely as the prominent voice of the Hindutva ideology, yet certain traits of Savarkar such as his atheistic beliefs, disdain for practices such as cow-worship and vegetarianism and especially his hatred for the caste system have the possibility of opening up conversations between the ideologues at the extreme ends of the spectrum.

This is especially true in Savarkar’s indictment of the varna order and the caste system in his 1931 essay Seven Shackles of the Hindu Society where vyavasaayabandi (restriction of occupation based on birth) and sparsabandi (untouchability) is listed among the seven shackles- distantly echoing the Ambedkarite opposition to varna-based order and untouchability.

However, at the same time one should acknowledge and dialogically resolve the vivaad between both the ideas- Savarkarite reinterpretation of the varna system as based on personal virtues and gradual succession in grades of consciousness up the system and Dr Ambedkar’s indictment of the same as ‘not merely division of labour but a division of labourers’ or ‘a system of graded inequality with ascending degree of reverence and descending degree of contempt’.

Similarly, the Savarkarite view on cow-protection such as ‘when humanitarian interests are not served and harmed by the cow…. self-defeating extreme cow protection should be rejected’. The concern for humanitarianism with respect to the holy status of the cow is also seen in Gandhi when he states in Hind Swaraj that if someone witnesses anyone from the Mohammedan community-consuming beef then instead of severely reprimanding or chastising his Mohammedan brother one should try to appeal to the conscience of the other and make him realize the importance of ahimsa even in deeds such as food consumption.

At a personal level the samvaads I had with my Left and Ambedkarite friends, Kashmiri and Manipuri classmates and Gandhian professors as well as the discussions witnessed among them did two things- widened my mental horizon and at the same time made me realise the commonalities between these ideas which are often overlooked.

An example is the similar views on the need of morality and religion in political discourse shared by both Gandhi (satyagraha) and Dr. Ambedkar (dhamma). Or the love for Bollywood cinema, Netflix, biryani, Anime, and K-Pop shared between my Kashmiri and me and Manipuri friends while at the same time seeking a peaceful resolution to conflicts and harboring dreams of a better and secured future.

Finally, I believe this should be the aim of samvaad– finding commonalities with the opponent (even at extreme ends of the thought spectrum) and addressing the difference (vivaad) while maintaining the respect and dignity of each other. Following these rules of samvaad can’t there be a conversation between extreme ideas at Gandhi and Savarkar on the excesses committed in the name of cow-vigilantism? Or between Dr. Ambedkar and Savarkar- the former on his insistence of inter-caste marriage as the sole medium of breaking the institution of caste while the latter addressing betibandi (prohibition on inter-caste marriage) as among the seven ills afflicting Hindu society? The readers can try.

Anuraad Khaund is pursuing Masters in Liberal Studies at Ashoka University, Sonipat

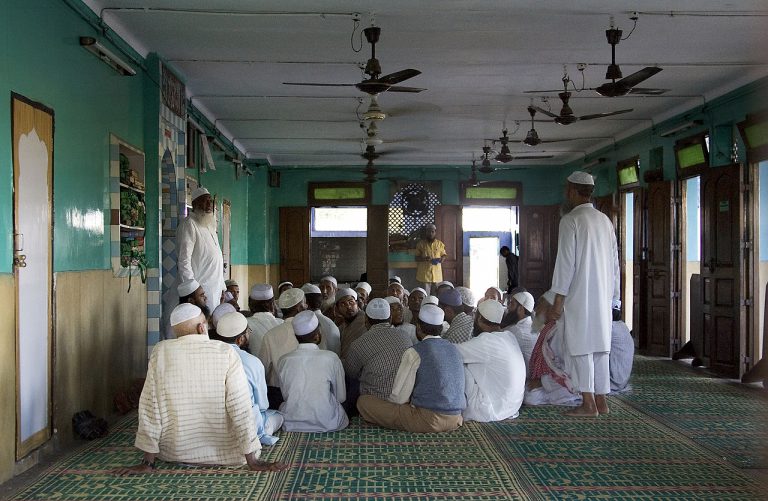

Featured Image Credits: Nwezzmaster

Readers' Reviews (1 reply)