Has Iqbal’s Pan Islamism done India more harm than good?

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Read out this Theel for me”]

The Indian Poet and Philosopher, Allama Iqbal, once said, “I lead no party; I follow no leader. I have given the best part of my life to careful study of Islam, its law and polity, its culture, its history, and its literature”. Allama Muhammad Iqbal also known as the spiritual founder of Pakistan, gave a very peculiar view of Pan Islamism to the world, a view that spoke of Muslim brotherhood, that explored how Indian Muslims needed a homeland; a homeland whose boundaries would not act as an obstacle in realizing the higher ideals of Islam. The grandson of a Kashmiri Hindu, who migrated from Kashmir to Punjab and converted to Islam, undoubtedly gave India the masterpiece of “Sare Jahan se accha ye Hindustan Hamara.” If India, for the 27-year-old Iqbal in the year 1906, was utmost fulfilled and the unsurpassed ‘Jahan’ (nation) to be a part of, then the question that remains is why did Iqbal at the age of 32 till his death, contribute to the making of Pakistan?. Most critics say that Iqbal imagined and envisaged the idea of Pakistan, but it was Jinnah who finally gave shape to it. But what remains undebatable is that Pakistan was indeed the spiritual brainchild of none other than Iqbal.

In 1937, Iqbal wrote a letter to Jinnah, in which he said, “After a long and careful study of Islamic Law, I have come to the conclusion that if this system of Law is properly understood and applied, at last, the right to subsistence is secured to everybody. But the enforcement and development of the Shariat of Islam is impossible in this country without a free Muslim state or states. This has been my honest conviction for many years, and I still believe this to be the only way to solve the problem of bread for Muslims as well as to secure a peaceful India.” For Iqbal, the answer to all these questions was Pakistan. For several authors of political thought, the reason why Iqbal emphasized the idea of Pakistan was because he felt Hindu leaders heavily dominated the Indian National Congress.

He visualized that Muslims would be sidelined from the picture of politics and development, even if India would become independent. While Hindus grabbed the opportunity of western education, generations of Muslims kept themselves away from such opportunities, on account of it being blasphemous and sinful. The Muslim mind was clouded with an orthodox thought that western education would strip them of a culture they were carrying on for ages. So while an educated Hindu had a chance in working in the British administration, an Urdu speaking Muslim man compared to this Hindu counterpart evidently had no chance for better jobs and posts in the British government. Muslims were far behind in the competition for positions and better lifestyle opportunities compared to the Hindus, and Iqbal knew that. Competition among unequal’s would remain unequal even if the country were free of its colonial rulers, and hence for Iqbal, there seemed no other escape; Pakistan was the only way.

One might say that such an interpretation of Iqbal’s Pan Islamism might be too radical, but one must realize that Iqbal gave secularism a back seat in his ideas of nationalism. He sought for universal brotherhood, but this brotherhood only gave seats to Muslims and not Hindus. Islam was a societal way of life, and not a private practice that occurs behind closed doors, hence for Iqbal if Islam was not given a pedestal and a platform in socio, economic, and most importantly political aspects of a man’s life, in a country where Muslims were a minority, the only option was to break away.

However, the question that comes to the mind is that, did Iqbal contemplate whether a state created to protect a community escape the domination of the Hindus and unequal competition, and to secure higher ideals of Islamic aspirations was inevitably bound to succeed? Did Iqbal fathom the fact that each time he asked Jinnah to lead the Muslim League, he gave in to the creation of a state via partition that would lead to agony and grievance on both sides for generations; a nightmare of partition, that India would not be able to wake from?

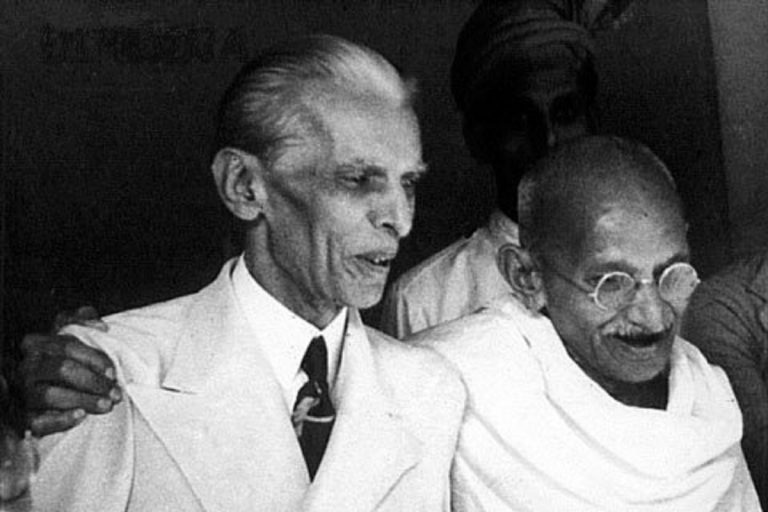

Whether the rhetoric of Iqbal’s Pan Islamism found a gateway in the pre-independent mind of a Muslim man or a woman is still subjected to various views and opinions. However, when the Muslim League secured not more than 12% votes in the 1937 polls, the Indian National Congress won over 707 seats. The Muslim League was left with only 100 seats. This only showed that Muslims had not lost faith in the Indian National Congress. Muslims could visibly see Muslim leaders like Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad gaining prominence in the sphere of politics, and if a party could culminate Hindus and Muslims together, then it was Indian National Congress and not Muslim League. Muslims put their hopes in the hands of Gandhi and Nehru, and not Jinnah.

Then what went wrong?

R.J Moore opined that what might have appealed to Muslims was that the idea of the consolidation of the Muslim state as a stepping stone towards the amalgamation of the world Islamic community to show Islam as a “peoples building force” and not just an “ideal.” An Islamic state like Pakistan could free Muslims from the clutches of Arab Imperialism and the obstacles of living under a Hindu majority state. The making of Pakistan for a Muslim, despite being illusionary, still seemed like a win-win situation.

In 2020, India and Pakistan would witness the 73rd anniversary of the partition, marking the goriest upheavals in human history. In the summer of 1947, 14 million people abandoned their homes, and an estimated 2 million individuals lost their lives. Hindus and Sikhs ran away from Pakistan, a country that would be Muslim-controlled, while Muslims fled in the opposite direction. The heritage of that violent separation was undergone, resulting in a rancorous rivalry between India and Pakistan that we still see today.

Nisid Hajari, the author of ‘Midnight’s Furies: The Deadly Legacy of India’s Partition,’ felt that, “Leaders on both sides wanted the countries to be allies like the U.S. and Canada are. Their economies were deeply intertwined; their cultures were very similar. But after partition was announced, the subcontinent descended quickly into riots and bloodshed. Bungalows and mansions were burned and looted, women were raped, children were killed in front of their siblings. Trains carrying refugees between the two new nations arrived full of corpses; their passengers had been killed by mobs en route. These were called “blood trains”: All too often they crossed the border in funereal silence, blood seeping from under their carriage doors.” Sudershana Kumari said that even the fruit on the trees tasted of blood, she said, “When you broke a branch, red would come out,” recollecting the image of how Indian soil soaked all the blood spluttered on it.

When Iqbal stood up at the Allahabad Session, held in December of 1930, and said, “I would like to see Punjab, the North Western Frontier Provinces (NWFP), Sind and Balochistan amalgamated into a single state. Self-government within the British empire, or without the British Empire, through the formation of a consolidated North Western Indian Muslim state, appears to be the final destiny of Muslims, at least of northwest India”. Iqbal’s Pan Islamism, owing to his study of Islamic philosophy, made him a firm believer that Hindus and Muslims are “two separate nations” that ‘cannot’ stay together; but if Iqbal instead would have preached that the Hindus and Muslims ‘could’ live together, then he would have probably saved the 20,000–25,000 Muslims who would have to wash their hands off their precious lives, for a state that he envisioned for them.

Iqbal’s Pan Islamism didn’t support hatred towards the Hindus, nor did it aim to promote ill feelings towards the other communities residing in India. However, Iqbal’s love for an Islamic state brought him to a crossroads where he had to choose between a secular nation intertwined with unity and diversity on the one hand and an Islamic state on the other. Iqbal’s choice was clear, and what he was not aware of was his choice would eventually lead the nation into an avenue, which was indeed dark and absolutely terrifying.

Featured Image: Wikipedia

Readers' Reviews (2 replies)