The Awkward Bourgeois: Role of the Armchair Critic in Neoliberal Democracy

Rufaida studies Political Science and is interested in different political theories and how they impact the world in a comparative perspective. Shikha lives in New Delhi and is a Pol. Science major at Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, Delhi University.

There exists literature in politics which establishes the necessity of being an active citizen; however, the implementation of this measure is far from ideal. The current state of affairs is such that the perpetually shifting socio-political milieu makes it near impossible for an individual to pay heed to key issues. Since becoming a proactive citizen is not a spontaneous venture but requires conscious effort vis-a-vis understanding our role within the complex dimensions of society, there has to be a primary step to facilitate this zealous spirit into something that is material. Fortunately, voting as a continuum of democratic participation is a method of empowering civic engagement. This brings us to perceive the various socio-economic characteristics of an electorate and the spatial context within which its political socialization has occurred.

The terms ‘middle-class’ and ‘bourgeoisie’ (land-owning upper class) are ones that we are all privy to. We hear it in our lecture halls, on the news, on our social media feed, etc. and yet, we do not fully understand the implications of it in the political context, or more specifically, voting behaviour. It pertains to the action or lack thereof, of citizens participating in their local, regional, or national election process. The bourgeoisie as a socio-political bloc has an identity largely associated with consumerist lifestyle. Among the middle classes, however, not all social groups enjoy equal dominance. The hegemonic position is occupied by the “new middle-classes” who have come to embody India’s transition to liberalization – the prosperous, young, metropolitan, invariably upper-caste and white-collared professionals – working in the private sector, who feel as at home in India, as in the West, with a consumption pattern similar to their western counterparts. What defines them and differentiates them from others are their lifestyle, consumption and social distinctions. The Marxist expression ‘sack of potatoes’ about peasant political consciousness holds true of the Indian middle class. The bourgeoisie remains indecisive when it comes to getting their index finger marked based on behavioural patterns of erstwhile election statistics. They are predominantly fence-sitters, not willing to join any side. Nevertheless, the middle-class is politically active, but this idea of politics is a more broad-based one where they try to influence power and policies and generate a collective.

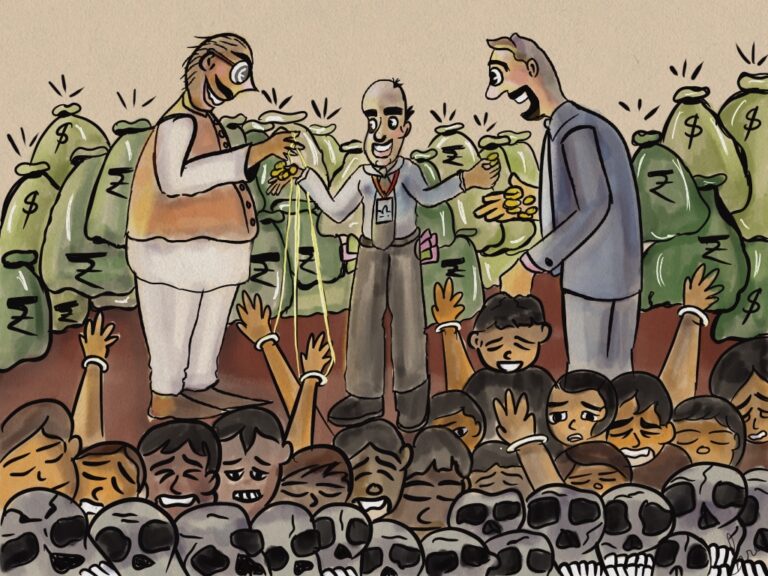

However, low voter turnouts in cities suggest that this pursuit is merely futile as it is not embroiled in the actual electoral process. The middle class’s electoral apathy, however, is not a one-sided affair. A cursory look at the manifestos of the main political parties for elections hardly makes space for specific middle-class issues. No major political party caters to the needs of the middle class in their speeches or their manifesto. The hardship of the middle-class is thus rendered persona non-grata. It seems we have reached an impasse, wherein none of the participants is willing to make amends to their approach. Consequently, the institutions that previously functioned proficiently due to a system of checks-and-balances, wherein the middle class had a vital role to play, have now switched their allegiance over to the highest bidder as opposed to serving the people. Due to the failure to respond to these exponentially deteriorating conditions of several institutions – academic, economic, judicial, political – to name a few, we are now in the midst of an incontrovertible assault on the secular fabric of our nation.

Using one’s political voice has a significant impact on the quality of governance, is indicative of an informed citizenry and holds the state to account. A people’s ability to freely express their views and dissent is characteristic of how tolerant a state is. This process of participation innately sparks demand for accountability and transparency and ensures a dynamic system of checks-and-balances. It is frequently stated that the middle class is the moral conscience of a nation and are upholders of democratic principles, and we strongly concur with this declaration. Unfortunately, while the old middle class was at the vanguard of the anticolonial struggle and post-independence asserted its leadership through bureaucratic and managerial control, the new middle class (or at least the dominant faction within it) actively partakes in self-destructive behaviour with unquestioning conviction in neoliberal doxa.

Calculative solidarity: The consequences of Neo-liberal apathy

Neoliberalism has been perpetuated amongst the masses to widely disseminate its direct and coded messages. This knowledge is reproduced by most institutions, and in social relations, human behaviour, expectations, in minds and bodies. This has imparted it with an assumed legitimacy: its ideas have been internalised and accepted as incontestable. Since the middle class, especially its thin upper stratum, has a stake in perpetuating this status quo, for, on balance, the gains of neo-liberalism are overwhelmingly in their favour; therefore, it is particularly sympathetic towards liberalisation and its ideology. The other strata of the middle class are, more often than not, uncritically accepting of the doxa. Against the backdrop of representative democracy, India maintains a distinct position wherein it is the dispossessed, the ignoramus and inconspicuous citizens who decide the fate of nearly every election. However, this is not to imply that the bourgeoisie does not play a vital part within the larger neoliberal framework.

Of late, the middle class has increasingly sought to influence national agenda and policies through new forms of citizens’ activism and on issues that directly affect it. Be that as it may, they have used their socio-cultural capital in contradictory ways: advocating radical change and preservation of tradition; liberty and authoritarianism; equality and hierarchy simultaneously.

It seems as though we have a colonial hangover (an assumption of western superiority) we cannot seem to do away with, and we embody this by our political conduct.

From a spectator’s perspective, the middle class occupies modern spaces of activism and participates in articulations of identity politics with an intersectional spirit. The only point of contestation is when this activism is warped by individuals for gaining social clout. Arm-chair activism has ushered in a new age of accessible conscious thought, wherein people are beginning to question their role in society, and they do so evidently through their social media platforms. Condemning preliminary steps of vigilance does not benefit a movement or its message, this merely stagnates it. However, to also realize that simply posting a story is not the pinnacle of one’s cognizance is an essential detail. Having those uncomfortable and inconvenient conversations with one another regarding various instances, combined with an online, a physical and an ever-evolving social presence help construct a holistic approach towards socio-political issues.

In view of the influx of #BLM posts within the Indian social space, a few imperative questions were raised. These were a reaction to the profound incognizance of the bourgeoisie. A tide of black squares were unveiled on thousands of social media feeds, and their bearers were blissful in their self imposed ignorance. This was in stark contrast to the response received by activists, students, intellectuals, artists and minorities in India. To extend messages of support and unity is something the bourgeoisie apparently cannot afford to bestow upon their citizens. While it may be effortless for them to chant “No Justice, No Peace”, this group sees no irony in their fervent support for equality and justice in America alongside their indifference to or even support for anti-discrimination in India and the Indian diaspora. Against the twin reality of rampant casteism, classism, sexism and disdain for the arts and dissent, for the Indian middle-class to acknowledge western-centric issues as legitimate, and disregard the struggle of their community is performative resistance at best and conscious complicity at worst.

We are amid an exceedingly apathetic socio-political ideology, one that influences how a seemingly vocal section of the populace – the middle-class – thinks and reacts. Nevertheless, if we can cultivate ignorance, we can nurture empathy as well. There is an undercurrent of countervailing tendencies even within the middle class, such as students, intellectuals, activists and artists, who fearlessly yearn for freedom in the streets. They have risen to the challenge and, as Pierre Bourdieu states, “critiqued doxa through individual agency”. In times of adversity, solidarity becomes strength; and to build upon this act of resistance, and challenge the institutions that uphold this doxa, is perhaps a contemporary form of civic engagement and the ensuing struggle of the conscious citizen.

References

- Rule S. (2014) Voting Behavior. In: Michalos A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Springer, Dordrecht

- Bhatt, Amy, et al. “Hegemonic Developments: The New Indian Middle Class, Gendered Subalterns, and Diasporic Returnees in the Event of Neoliberalism.” Signs, vol. 36, no. 1, 2010, pp. 127–152. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/652916. Accessed 17 July 2020.

- Leela Fernandes, Hegemony and Inequality: Theoretical Reflection on India’s ‘New’ Middle Class, In Baviskar and Ray, Elite and Everyone, p 69.

- Singh, Richa. “Indian Middle Classes, Democracy and Electoral Politics”. Heinrich Böll Stiftung, The Green Political Foundation, 28-March-2014, https://www.boell.de/en/2014/03/26/indian-middle-classes-democracy-and-electoral-politics?dimension1=ds_india#.

- Nayar, Lola, and Jyotika Sood. “Anatomy Of A Middle-Class Electorate: Neither Forward Nor Backward, Just Awkward.” Outlook India, The Fully Loaded Magazine, 13-May-2019, https://www.outlookindia.com/magazine/story/india-news-anatomy-of-a-middle-class-electorate-neither-forward-nor-backward-just-awkward/301534.

- Menocal, Alina (2014). What is political voice, why does it matter, and how can it bring about change? Development Progress Discussion Paper Number 8950. Available at: https://www.odi.org/sites/odi.org.uk/files/odi-assets/publications-opinion-files/8950.pdf

- Salman, Aashti, and Balu Sunilraj. “As India’s Poor Demand Relief, Why Are Middle Classes Silent?”. NewsClick India, 16-April-2020, https://www.newsclick.in/India-Poor-Demand-Relief-Middle-Classes-Silent.

- KUMAR, SANJAY. “Patterns of Political Participation: Trends and Perspective.” Economic and Political Weekly, vol. 44, no. 39, 2009, pp. 47–51. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25663594.

- Leela Fernandes, Hegemony and Inequality: Theoretical Reflection on India’s ‘New’ Middle Class, In Baviskar and Ray, Elite and Everyone, p 69.

- Jos Mooij and Tawa Lama-Rewal, Class in Metropolitan India: The Rise of the Middle Classes, in Joël Ruet, Tawa Lama-Rewal, ed., Governing India’s Metropolises: Case Studies of Four Cities, Routledge; 2010.

- Cherian, Divya. “Seeing India Through the Black Lives Matter Protests”. The Wire India, 09-June-2020, https://thewire.in/rights/seeing-india-through-the-black-lives-matter-protests

Featured Image Courtesy of Taylor Vick on Unsplash.