Journeying as a Feminist

Shruti is currently pursuing a double Masters in International and World History from Columbia University and the London School of Economics. She also heads Advocacy and Engagement at NETRI Foundation.

“I am Shruti Sinha and I am a feminist.”

Critically engaging with texts and policies using the lens of gender, raising concerns connected to the subjugation of women, advocating for empowerment has become a part of my daily routine- it has become an easy task – almost natural.

Yes, all too easy- until I decided to write this article.

“I am Shruti Sinha and I am a feminist.”

“Yes, you’ve already stated that twice. But what do you mean when you say that? What makes you a feminist? What does feminism mean to you- what is feminism? What is your story?”

And that is where I stop every time. But this time is different- I am going to write my story.

My story begins in the year 2013, when I finally got admitted to my dream college- The Lady Shri Ram College for Women (LSR). To be honest, I went completely by the rankings- it was touted as the best liberal arts college in the country, and I wanted to study my favorite subject, which was Political Science. I did some research on Google, every now and then. The college was an all-women’s institution and had produced some outstanding women- Aung San Suu Kyi, Vinita Bali, and Nidhi Razdan stood out to me. The simple red brick building amidst the green lawns spread across the campus seemed very homely. But little- so very little- did I anticipate that the three years in the institution were going to change my life forever.

As it happens when one is in college, I had many firsts. But the most significant first was to be introduced to the term “feminism.” At the outset, it seemed fairly uncomplicated. I was handed this new academic concept, and I had to learn about it. But, very soon, I realized that to get a grasp of the concept – I had to unlearn how I was wired to think and perceive the world for the first eighteen years of my life. The process was intense- new ideas were introduced to us in class, leaving us astounded and shocked, heated debates with classmates ensued, and so did arguments at home; I was in a constant dialogue with my self and felt myself going into a prolonged identity crisis. Often, there were tears.

It was as if there was an awareness- a realization that it was our placement to the centers of power in the family, state, and society that determined our everyday living- from access to agency. For women, this power equation was gendered, and there were structures in place throughout the millennia, only changing in form and manifestation, which enforced the status quo of power relations. For instance, I realized for the first time that my mother wouldn’t have had to forego advancement in her career trajectory to be on the move with my father for his career growth had ideas and structures of family and motherhood not been skewed in favor of the “man is the breadwinner” narrative; or, if workplaces and state policies facilitated women with children and families to advance in their careers, as men with children and families could. I realized that the length of my skirt and the cut of my sleeves did not determine the rationale behind being sexually assaulted. Soon enough, the gender lens became a part of my vision.

While at one level, I dealt with the concept academically, I was also shifting gears in my everyday living. Back in my co-ed schooling, any heavy load was automatically carried by boys; we were constantly made conscious of the presence of boys and how that meant “sitting decently” or ensuring that our bra straps weren’t visible even for a moment. In an all-women’s institution- we, women, were carrying heavy loads, and no one was telling us to be conscious of how much of our underwear was visible when we sat with our legs perched up. It felt very freeing.

When I graduated, I left the institution with two of the greatest gifts for a lifetime. One: My friendships with incredibly smart and driven women who went through this process of learning and unlearning with me. Women I had cried with and laughed with, debated, and fought with, shared opinions on every matter from politics to sex with and confided my deepest and darkest dilemmas with, and vice versa. I see them now, and my heart swells with pride. They remain my safety net, safe space, and sounding board, and it is heartening to see each of them on their journeys to become kind, just, and humane leaders. Two: The concrete ambition to become a leader. When I was fourteen, I had decided that I was going to join politics in India. I had designed my logo and even named the party I was going to launch- Sarva Janhit Party (All People’s Welfare Party). By the end of school, I had even decided on my Prime Ministerial cabinet. While I always believed that there was nothing absurd about this dream, and I had full support from my forward-looking family, it was at LSR that this idea became a goal, and I wanted to take concrete steps to work towards it. I was ready to take on the world and “lead with social responsibility.”

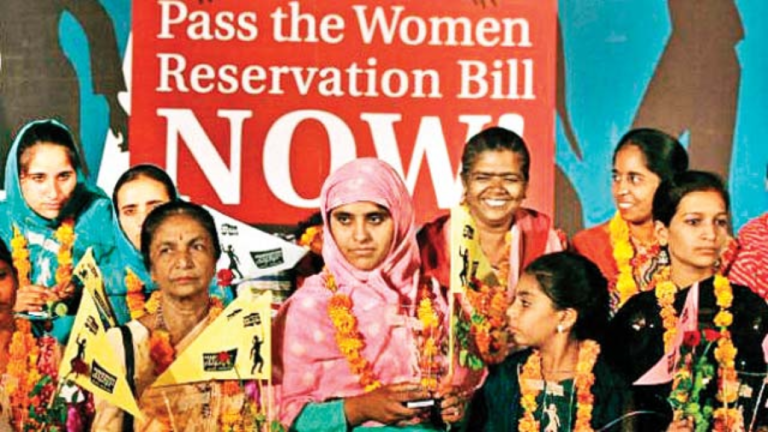

But was it that easy? After all, I was out of the feminist island and in the “real world.” I began working with a Member of Parliament, and one day we had a visitor. As he waited to meet my boss, he struck up a conversation with my male colleague and me. In the first five minutes of the conversation, he lauded both of us for taking the plunge and working with someone in politics. He told my male colleague to contest elections; to me, he said I should dedicate my life to working for members of parliament. And it hit me then. My gender would keep me from being viewed as a potential or credible leader regardless of my competence or efficiency. The blatant discrimination struck hard. We, women, had a long way to go. In my successive workplace, too, I realized that while I was viewed as a dependable and competent worker, it was a certain hyper-masculine leadership that perpetuated. The journey toward leadership wasn’t going to be an easy task. The statistics proved it too; the year is 2020, and less than 7% heads of states in the world are women. Overall, only about 25% of women world- over are in positions of political leadership.

It is in this sphere of bolstering women’s leadership and empowering our agency that I now work in. I am at the intersection of academia and policy. As an academic and a current student of international history, I realize that women’s voices and narratives have been absent and systematically marginalized from intellectual discourse. Fighting patriarchy that pervades academic writing and narratives is a conscious choice and commitment. My effort is to bring out stories of women leaders and shapers in history and assessing and acknowledging their impact. At the policy level, I see many young women running organizations encouraging women in leadership- a very positive trend. I happen to be associated with one such organization myself, NETRI Foundation, founded by an inspiring young woman, which works to amplify women’s participation and leadership at all political levels in India.

And yet, feminism is in danger.

Many young people- adolescents and young adults- seem to be rejecting feminism. They have stopped seeing the value in it- and would instead call themselves “equalists” and “anti-feminist.” What is also worrying is that those who recognise themselves as feminists are either disdainful or dismissive of this dissent instead of making an active effort to understand why the movement is falling into such disfavor or engage in dialogue. This is only adding to the polarization, and in the process, we are losing champions for the cause. Indeed, there is nothing more painful than finding a movement considered obsolete, not because it isn’t required anymore, but because it fails to connect and convince.

Therefore, it becomes crucial for us, feminists, to reassess the movement, re-align, and then activate.

So, what is feminism?

Feminism is a movement that has spanned over several decades. It is a tradition of thought and theory and of advocacy and activism against structures that have historically prevented and continue to prevent the realization of one’s true and full humanity by generating boundaries of masculinity and femininity.

- These boundaries that have been generated from biological differences between the male and female have taken forms of political, social, economic, cultural and perceptional oppression- patriarchy- perpetrated by the predominant male to essentially regulate the process of reproduction- thereby controlling women’s bodies and sexuality, rewarding conformity and punishing and disparaging “deviance.”

- As is the case with anything that is a movement, feminism has demanded different things ranging from sustainable development to world peace to ending child trafficking and cross-border terrorism- depending on factors like time and location, as well as the form of patriarchy it is fighting against.

- Feminist advocacy and activism, can then, not only mean different things depending on the context but can also be individual or intersectional or collective, and sometimes even a combination.

Intersectionality is Essential

The increasing use of social media platforms for activism and counter-activism has also served to alienate people from the cause. These platforms remain undemocratic and elite. A study finds that in India, women users of social media only comprise a third of the total user population. Further, only one of four women voters have any exposure to social media. Thus, if we recognize that feminism should be inclusive of intersectionality, then using platforms that remain inaccessible to the masses cannot become the mainstream mode of activism. Not only has this prevented a large number of women from connecting with the movement but has also really limited the scope of the movement to an urban elite class.

We have to write more, speak more and connect more in languages that go beyond English and Hindi- in the vernacular, and equally engage with everyday challenges faced by women in different intersections. In other words, we have to constantly be in dialogue and conversations with a wide range of women and from a wide range of backgrounds. Spaces for these wide-ranging, intersectional concerns have to be consciously created, and alternate feminisms should be acknowledged.

We have to lead for one another, and we have to follow one another. Our power lies in creating feminist solidarity and a network that recognizes the nuances and importance of intersectionality.

Men are not the Enemy, Patriarchy is

One would think that this is self-evident, but sadly not. A significant allegation that we face as feminists is that we are “anti-men.” That is not true. Feminism recognizes that men are trapped in the binaries and boundaries generated by patriarchy and envisions a world/society where these barriers don’t exist. We often hear statements like boys don’t cry; boys don’t play with dolls or wear the color pink. Feminism seeks to free men from these binding structures, as well. In the campaign against patriarchy, men are viewed as collaborators and fellow advocates.

Feminism is an everyday personal journey

I cannot stress enough on the importance of this aspect of feminism. If anything, feminism is, foremost, a major process of unlearning. This process of restructuring the way we have been socially conditioned is one that can shake you to the very core. As I described my experience, it was a very intense and turbulent one. Feminism is a process of critical engagement and dialogue- not just externally- but with one’s self.

For instance, feminism tells me to love my body and that beauty standards are transient and constructed, and yet, I am faced with self- generated body image issues every single day. My mind is in a state of dialectic – my new learning constantly challenges my conditioning. But I am content as long as I know I am unlearning, little by little, every single day. I tell myself:

“Miles have we traversed in search of light, and yet, there remain miles undiscovered. Have courage, dear comrade, together; we shall find the light.”

Featured Image Credits: Gulabi Gang

Yes many people still see feminism as something that is rebellious and hating men. But little does our education system teach such important topics to the kids. It took me some time to understand what feninism is and since then i have felt the need to educate more people about this. Maybe its the word fem that triggers most people into rejecting the whole idea.

It’s not just men who are the collborators of patriarchy, we find women also are equal participants in it.