Who exactly is the protagonist in the Indian motion picture?

Who is the protagonist in the Indian film? American critic Margaret Redlich who specializes in Indian film thinks that the protagonist is mostly the titular character, but his/her position as a protagonist is supplemented by a number of other unique, distinguishable traits. It is her/him whom we see in the opening (or first few) shots and closing shots, whose life goes under the maximum challenges and changes. Our cine eye is overlapped with his/her eyes. This means we see the film through his/her perspective. Even when all fails, it is the protagonist whom you root for. It is his/her grief or joy that makes you feel most empathetic. Rest everyone, not so much.

However, not all movies have followed this pattern. Some movies try to show a more neutral perspective by either putting in a narrator. Or by showing the perspective of different characters via other means. Some of these movies have been discussed below.

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998)

Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998) is a good example in investigating who exactly is the protagonist. The title doesn’t feature any characters name. The opening shots are confusing and misleading. We don’t see Anjali (Kajol) till much later. However it’s Anjali’s grief who the audience truly and deeply feels for. Her unrequited love, her sad farewell to Rahul and Tina, his entry again in her life, her sucking in a whirlpool wedding she deep down doesn’t want. She went through the maximum external and internal changes throughout the motion picture. Of course, Tina (Rani Mukerjhee) is pretty and virtuous and Rahul (Shahrukh Khan) may be immature but is after all is a good lad. They are perfect and happy and are just like any other good college kids in love. However its Anjali’s heartbreak which remains the crux of the plot and whom the audience ends up feeling the most intensely. It’s a deeply realized and wonderfully performed character.

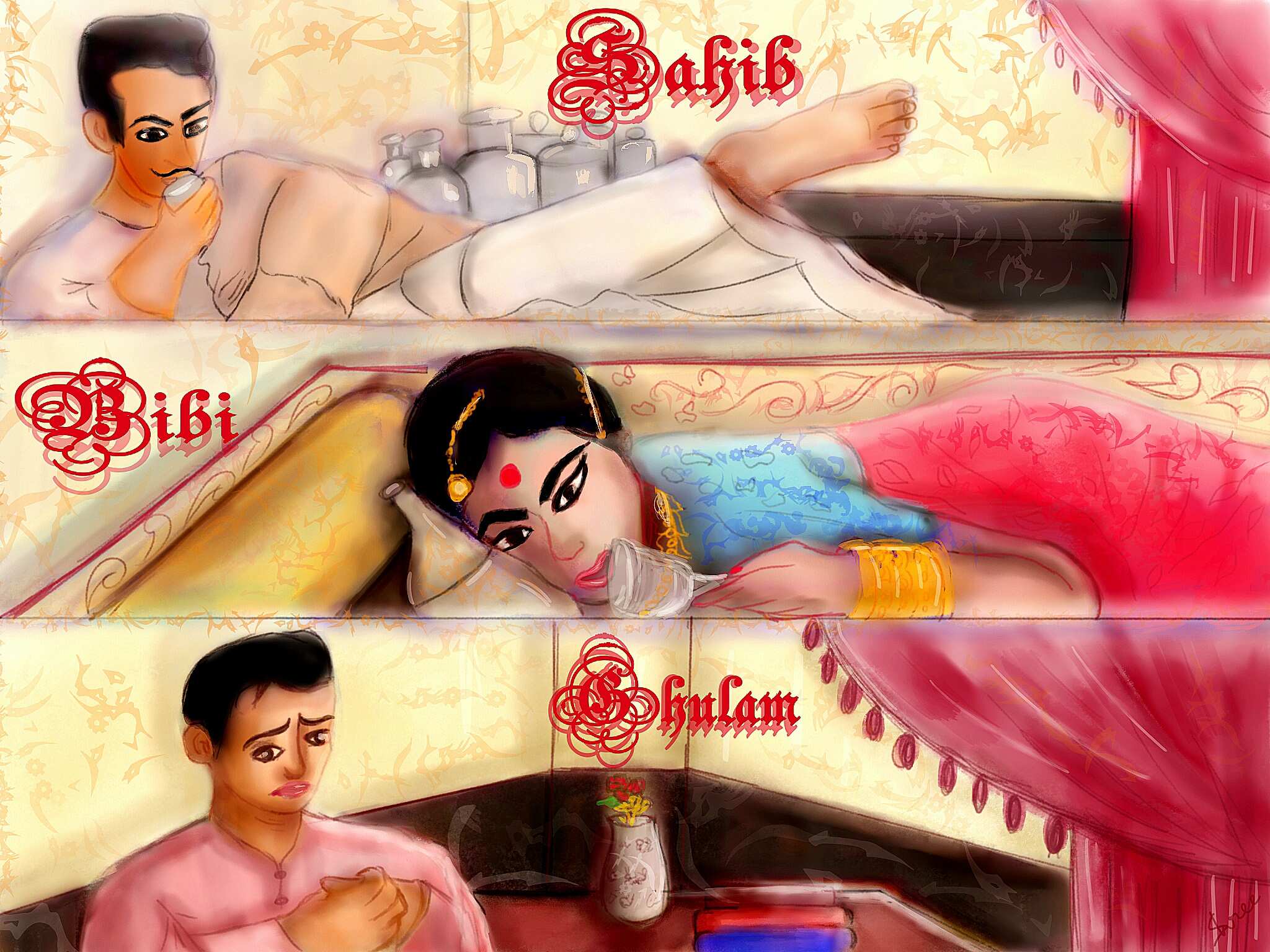

Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam (1962)

Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1962) is another wonderful example of investigating who exactly is the protagonist. Widely regarded to be Meena Kumari’s career’s best performance. We have three characters in our title – The master, the wife, the slave. On an immediate level, there is no judgment. All are equal. Or is this following a patriarchal feudal hierarchy? Neither! The master is a feudal lord dribbling away his wealth on alcohol and nautch girls. His young wife pines away for his affection. He challenges her to become his drinking companion if she wants him to stay with her at night and not the upmarket brothels. She loathes liquor but forces herself to drink to make him stay. At the pinnacle of the film, she becomes an alcoholic while her husband gets paralyzed due to a brawl. Choti Bahu gets the maximum screen time (Meena Kumari really commands your full attention through that magnetic screen presence in her huge eyes). Earlier drunk with tender youthful love and now with perpetual intoxication.

This story is told from the lens of the servant who is hopelessly sympathetic to the unending misery of the household. So one of the titular characters is the antagonist, the second the protagonist and third the narrator with more or less no say in the actual proceedings. We see through his eyes and feel as helpless because despite our goodwill, these events in the film unravel so disastrously, we really can’t do anything to prevent the tragedies. It might feel that an

Indian film might rest entirely on the shoulder of its titular character and it’s all about him/her (often HIM, HIM and only HIM). But if supporting characters are well written and acutely performed enough, it can become about everyone. Everyone gets their moments to shine onscreen. It becomes about their thoughts, feelings, soft heart breaks, unspoken moments their mutual bonds, broken and unbroken. This is how it plays out in real life as well. Not always in big dramatic moments but in silence and subtlety too.

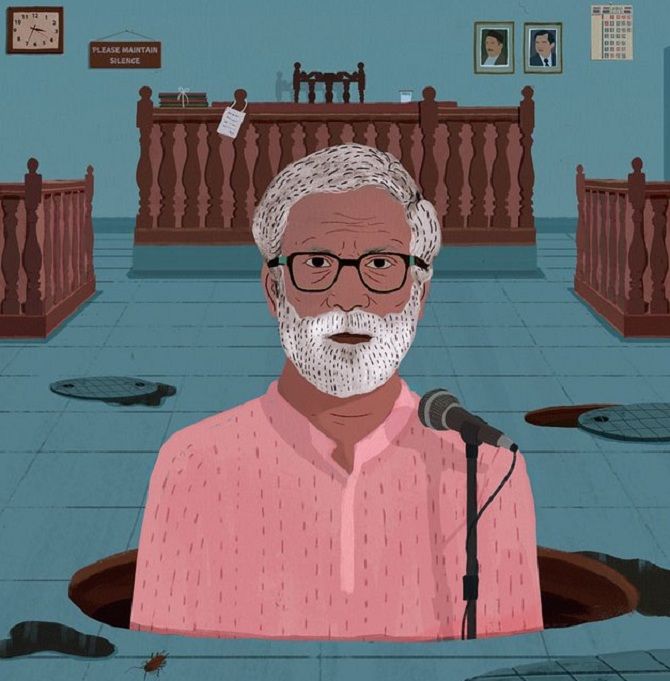

Devdas

Devdas is a great film that is a type of the one given above. It’s also an excellent example of a Greek tragedy (brought on himself by the protagonist). It has been adapted and has inspired so many Indian films indirectly, its impossible to keep a correct count.

In case you haven’t read the novel or seen any adaptation into film, here is the brief overview of the story. The films vary in exact details so I first describe the plot as in the novel written by Sarat Chandra Chatterji. It was published in 1917, though the author had finished writing it by 1900.

Devdas Mukherjee and his neighbor Parvati (Paro) are friends as children in a nineteenth century Bengal village Manikpur. He goes away for higher studies and returns as a young man. They fall in love and share a short blissful courtship but his father won’t allow the marriage. She marries a rich feudal lord in revenge while he becomes an alcoholic. He lives in up market brothels and ultimately falls in love with Chandramukhi, a prostitute. Only to discover that alcohol has eaten away his system. In order to keep the promise he made to Parvati (that he will meet her once before dying), he boards a train to her house. He reaches her house on a cold, rainy night and dies at her doorstep. Parvati is stopped by her in laws from meeting him for the last time.

On the surface it looks like any other Indian film that glorifies suffering in the most romantic and visually stunning manner as possible. This may be especially said of Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s version of Devdas (2002). But actually Devdas is much more than what casually meets the eye. Sure, he is the title. We open on him but mostly close on Parvati. We do see the upper caste nineteenth century Bengal through his eyes, he gets loads of screen time. It is about him, but it isn’t just about him. It is about time and the personal evolution brought by the passages of time and the transformational power of deep rooted grief. And to do so, almost equal attention has been given to the inner tumult of all the characters.

Devdas loses Parvati and takes to alcohol. Over a period of time, he gets addicted. Alcohol wipes away his physical power and grief accumulated over months dissolves his will to live or fight (he walks away from his inheritance without a word). When he believes he doesn’t want to live, life shows its unpredictable colors again and he realizes he is in love with Chandramukhi. The first time, it wasn’t the right time, the second time, he has no time.

Chandramukhi gets the classic character arc of the redemption of the ‘sinner’ through love. It fits the theme of the novel. She starts with the perfect vision of male fantasy – erotic. With time (through the eyes of Devdas – because his eyes are our cine eyes), we start seeing the humane emotions behind the heinous reality of flesh trade that is whitewashed as romantic and beautiful in Indian films. She realizes that she is human as much as anyone else and is capable of actually falling in love as much as she is capable of trading herself.

What about Paro?

Parvati goes through the maximum changes. From a picky, arrogant child to a young passionate lover who cared for nothing else but her love. The wild passionate experience of first love makes her forget everything – reputation or family or social status or anything else in the way of true love. After losing Devdas, she becomes a restrained and tight-lipped silent figure, as if life has been extracted away. Through marriage, she turns to a rich socialite who despite enormous wealth and power, no longer desires anything for herself. She is dissolved in a cloud of grief internally while exercising her warm maternal duties externally. All wants are finished. She becomes a patron to so many charitable causes and gives away so much, her daughter in law is forced to stop her!

Which also brings me to the entire concept of identifying lead in the Indian film. Supporting characters are often sacrificed at the altar of glorifying the protagonist. This was especially true in 1980s and 1990s. The hero is the greatest and best thing to ever happen! Bow to him! The heroine is pretty and all she can do is love the hero, the friends are caricaturist empathizers, the villain makes the life of the hero miserable in the most unrealistic and dramatic fashion as possible and so on. But there can also be films from the perspective of the friend, the lady love, the villain. There can be films with them as the center too.

And yes, there are films which “accidentally” make someone else the protagonist. I think this happens when either the supporting artist is actually the better actor or more often than not when this character has more human layers. Shades of white, black and grey strike out for the audience. Further this character has complicated conflicts to handle and decisions to make. He/she has to make the greatest cause supreme, choose happiness for the maximum number of people. Only this choice can highlight him/her better as the protagonist and metaphorically larger than him despite literally less time on screen (think of Kashibai from Bajirao Mastani) our protagonist can be subjective too!

What an impressive writing that too at such a young age. Really a interesting take on female protagonists as hero

So well written! Keep it up!!!

Choosing “the hero” couldn’t have been explained better! The dilema that every cinema enthusiast has to overcome.??