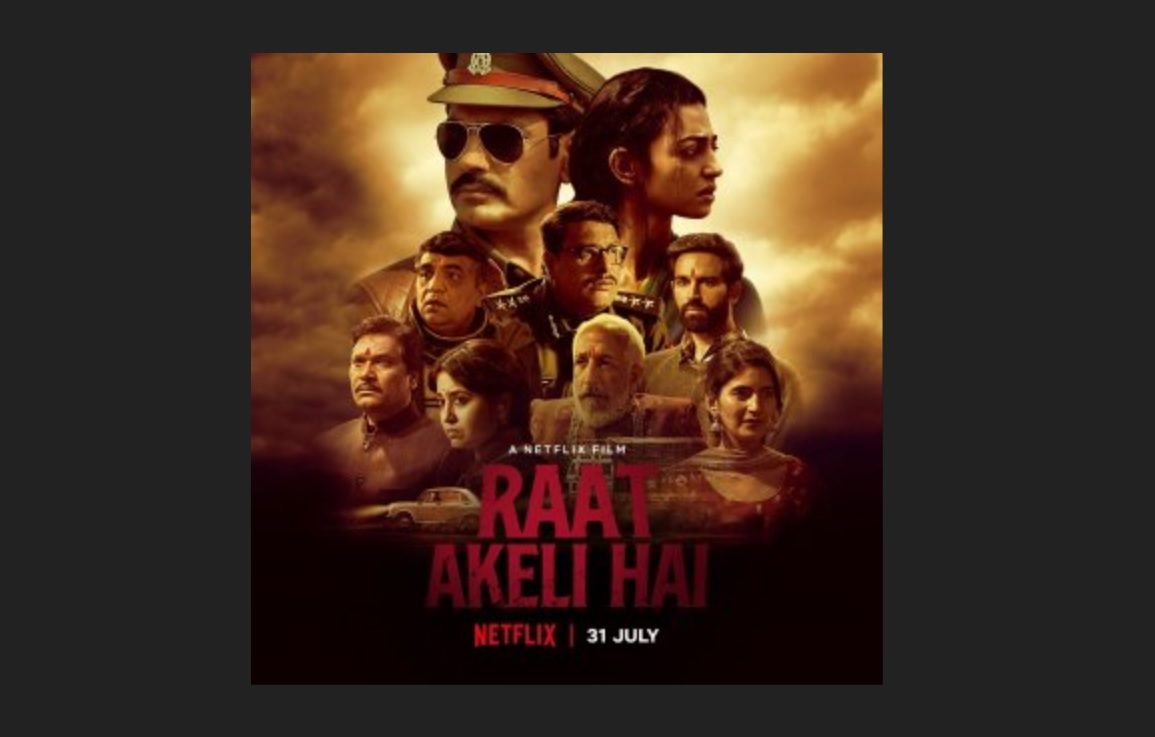

Raat Akeli Hai: A story hidden in the shadows

A film noir is about revealing the secrets in the shadows, the sins society hides away, bringing them into the light, and forgiving them. Other movies have a harsh line between good and evil. Our heroes and heroines are perfection defined, sinless. And our villains are inhuman; one could show no sympathy for them. A film noir has a different approach. What makes you a hero is attempting to grow past and overcome your sins. What makes you a villain is that you have failed and must live with the guilt of knowing what you are.

This is the opposite of the standard mainstream Hindi film style. This is not a clear, colorful world where the hero is perfect without effort, and the villain is villainous because that is his nature. This is something closer to the real world, where life is more complicated, and people are more complicated.

The term “film noir” refers specifically to the film style wherein everything is shadowed and dark. The movie under purview here lives in the shadows. The cinematography is subtle, but it is not casual. There are a few moments carefully constructed for maximum impact; for example, the first time we see our heroine, her face changes in a few seconds as she walks across a room or a shot in which a bloody handprint is left on a political poster. This is the first film of director Honey Trehan, and it is an excellent debut. Full credit as well, to the cinematographer Pankaj Kumar (Tumbbad, Talvar, Rangoon), who keeps up his high standards.

The visuals set the tone for the story the film wants to tell. Just as we can only half-see what is onscreen, so is the truth of the characters, which are also left only half-seen. This movie creates a world in which most people are pretending to be good, trying to play that role, but almost no one is. At one point, our police officer Jatil Yadav’s (Nawazuddin Siddiqui) mother compares him to the actor Ajay Devgan, playing the role of a police officer, and we can see that Jatil himself craves that comparison. He is a police officer who wears sunglasses and rides a motorcycle, who tries to present himself as the perfect hero but at heart, feels that he is not good enough. Later he dismissively refers to the handsome, wealthy young male suspect in his latest case as “that Hero.” This is what a hero should be, rich and handsome and respectable. Jatil is not that hero, although he aspires to be it. And of course, the handsome young man is not really much of a “hero” either. He, too, is just trying to play the role he thinks he should play – a good son and responsible head of the family and loving fiancé to a proper young woman.

The greatest shadow hangs over the world of women. This film shows women hidden away in big houses, their actions overlooked, their tragedies ignored. But that can be a strength. While the men are blustering and demanding and trying to control the world, the women slip silently through it, doing what they like, creeping through the shadows. Radhika Apte (Andhadhun, Sacred Games, Kabali) as the new bride, Shivani Raghuvanshi (Made in Heaven) as the young niece, Shweta Tripathi (Mirzapur) as the married daughter, and Ila Arun (Manto, Jodha-Akbar) as the widowed aunt – all give phenomenal performances playing characters who are far more than what they seem.

Film noir can be a wonderful genre for women. The great Waheeda Rahman was first discovered by the Hindi audience playing the tragic “bad” woman in the Dev Anand classic CID. More recently, Badla gave Taapsee Pannu and Amrita Singh a chance to square off against each other. And of course, Ittefaq, both old and new, brought into question assumptions about beautiful young wives and the simplicity of their thinking. Kahaani is the most powerful of them all, wherein a female character is seen only through others’ eyes, giving them the story they want and the person they want to see, until the audience is stunned by the late revelation of her truth.

It is that grey area between “good” and “bad” that allows female characters to thrive in this genre. A typical Hindi film has three central characters, protagonist and antagonist, and love interest. The “love interest” part is usually played by a woman; she exists in a neutral zone between the protagonist and antagonist. She is neither good nor bad, just there, fulfilling her plot requirement as a goal and distraction for the protagonist, sometimes a coveted object by the antagonist. But what happens when the other two parts of the triangle shift, when the protagonist and antagonist are no longer so strict?

In this film and most noirs, the hero lives in a world where everyone is rotten. It is not a matter of setting himself up against that one big bad, more of setting himself up against a failed society. And it is a matter of him failing as well sometimes. Suddenly the “love interest” role can become so much more. If all of the society is rotten, then women can be rotten too. Not rotten from the inside, not inevitably broken, but rotten from the outside, from what the world has done to them. Noirs thrive on setting up the usual “virgin-vamp” dynamic and then burning it down, revealing that the “virgin” is not so innocent and the “vamp” is not so broken. Everyone is just playing a role; their truth lies underneath.

Noirs challenge us to confront our expectations. When we see a beautiful young woman asking for help, do we assume she is fragile and innocent, and the man she accuses is a brute? When we see a husband declaring his wife unfaithful, do we believe him and reject her without thought? Women are always trapped by expectations. They are told they are “good” or “bad” and must face the consequences and live with the results. Noir is one genre where the female character is allowed a second chance, allowed to grow beyond those simple limits.

Noirs have always been a part of Hindi film, going as far back as to the late 1940s. Just in the past few years, we have had Andhadhun, Ittefaq, Badla, Kahaani, and now this movie, along with Article 15, Pink, and some other slightly more political versions. They are all about dark worlds and dark people where nothing is as it seems. The stereotypical Hindi film is one in which the hero is the hero, and the villain is the villain, and everything is bright and clear and sure. But that world can only exist because the hidden dark world of the Noirs goes along with it. Some parts of the audience will always crave uncertainty, will always need that bitter taste to help them enjoy the clear, easy flavoring of the mainstream film.

Don’t watch this movie as you would watch the usual mainstream Hindi film, the one that tells you exactly what to think and why. This is a movie that rewards close watching. Watch it, and watch yourself watching it. What assumptions do you make about the challenges this film poses? What prejudices does it reveal? What are the shadows in your own mind?

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia