Just Another Election

Dilip Simeon is a teacher and taught at many universities across India and the world

(Published in Mint, Saturday, April 4, 2009)

Early in 1977 I attended a mammoth meeting on Ram Lila maidan celebrating the end of the Emergency. Jagjivan Ram had joined the opposition. Jaiprakash Narain, Acharya Kripalani and the Imam of Jama Masjid were present. Amidst lusty cheers, Jagjivan Ram hailed Indian democracy, wherein a princess was equal to a sweeper woman. Sick of authoritarianism, the public voted the Indira regime out of power. Three years later, I spoke to a tea-vendor in Patna, eking out a living on the roadside. I asked whom he was voting for. He replied, “hum to Indiraji ko vote denge”. When I reminded him about the Emergency he said that Morarji Desai and the Janta Party had been given power for 5 years, but disintegrated in three. “Chor-char ke bhag gaye” was his colourful description. What was the point of asking such people to govern again? This humble citizen had a modest expectation of his government – that it fulfil its mandate for the appointed term.

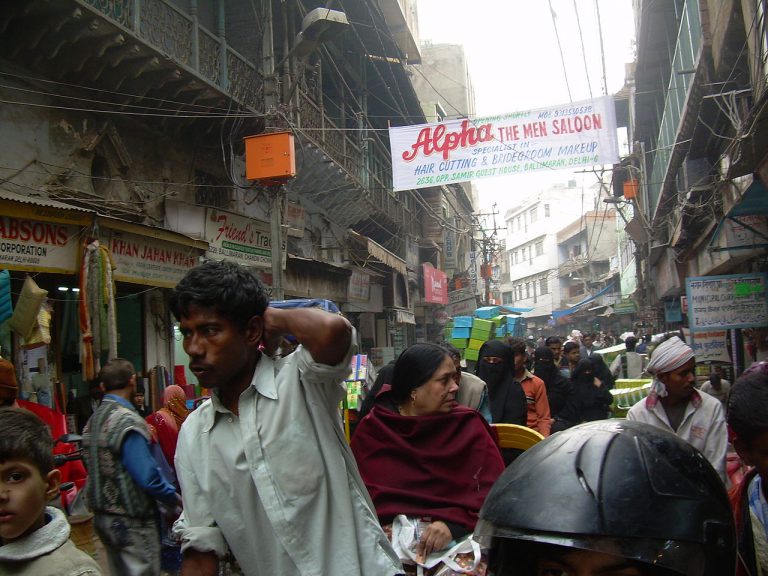

In December 1984, I joined Swami Agnivesh’s campaign in Bhopal, where he stood beside victims of the gas disaster. After the communal carnage of November, it was exhilarating to see burqa-clad women from victims’ organisations along with Malayali members of a karamchari union, campaign for a swami in ochre robes. The same election elicited a boycott call in Bihar by Maoists. “Bullets, not ballots” was the phrase used. The response was unique. The oppressed groups that were the support-base of the insurgency insisted upon their right to vote, if necessary by violent means. Landowning castes were served notice that they could no longer highjack democracy by stuffing ballot boxes. Thereafter a moderate stream of Naxalism sought popularity by protecting the peoples’ right to vote. The self-styled leaders of the oppressed were taught a lesson by their followers.

Indians have become accustomed to the electoral process. For all its defects, the prolonged mass movement for independence nurtured a democratic political culture. Efforts to curtail it will meet with resistance. Despite her autocratic tendencies, Indira Gandhi had the sense to withdraw the Emergency. This is why right and left-wing projects of radical political change seeking to overthrow the Constitution have not succeeded, and their proponents obliged to adjust their utopias to the Indian preference for democracy. But a question remains: have the mainstream parties strengthened Indian democracy?

Elections bestow authority upon officialdom and governments. The bureaucracy, judiciary and police derive their powers from the Constitution. This document gives us a means of evaluating the health of the polity. Article 21 states that none may be deprived of life or liberty except by lawful procedure. Article 49 protects monuments from spoliation and destruction. Articles 23 and 24 prohibit human trafficking, forced labour; and the employment of children under 14. Article 48-A enjoins the State to protect the environment, forests and wild life. Article 51-A informs citizens of their duties, which include promoting harmony transcending religious, linguistic and sectional diversities; upholding women’s dignity; safeguarding public property and abjuring violence; protecting forests, lakes, rivers and wild life, and developing the spirit of inquiry and reform. The Directive Principles list fundamental goals that the State is duty-bound to apply. These include a just social order, the management of material resources for serving the common good, an economic system that prevents the concentration of wealth, and justice that is not curtailed by economic or other disabilities.

An appraisal of our history speaks volumes about how far the aspirants to power have upheld constitutional norms. On a minimalist standard, the important contestants have not even respected the citizens’ right to life and liberty, and the rights of small children. India’s leading political parties have unleashed captive mobs upon our fellow citizens, most notably in 1984 and 2002. The activities of militia such as the Ranvir Sena and Salwa Judum are condoned by the State. Certain states are under permanent emergency, with security forces enjoying impunity for decades. Hindutva groups relentlessly pursue hatred – the attacks on Christians in Orissa and women in Bangalore are their latest gifts to the nation. In November 2007, the West Bengal government enabled partisan violence in Nandigram. Taslima Nasreen was hounded out of Kolkata after riots by Muslim fanatics.

Disrespect for law by mainstream politicians is the most dangerous aspect of our polity. Along with state officials, they would benefit from a close study of the Constitution. The disintegration of every polity in India’s neighbourhood should serve as a warning to the Indian establishment, which has often crossed all limits of lawful conduct and encouraged behaviour detrimental to the legitimacy of the Indian Union. The citizens’ expectations are straightforward – transparent government, neutral policing and a fair judicial system. These requirements are institutional, not material. People do not want government to give them jobs or food, so much as an environment in which they may work and feed themselves. These requirements are provided for in our Constitution. But it is precisely these simple needs that have been ignored by the political leadership.

The electoral process is a manifestation of these issues. Thus, to demand high office on the ground of one’s identity or sectional animosity is to appeal to the most primitive instincts. Such claims have become blatant in recent times. Past elections have seen the manipulation of electoral lists to deprive people of voting rights, booth capturing, intimidation and the use of liquor as an inducement. The election-rigging that took place in Jammu & Kashmir in the decades leading up to the insurgency undermined the peoples faith in the Indian Union more than any other factor. Despite all this, on crucial occasions citizens have used elections to enforce accountability upon arrogant leaders. This happened in 1967 when non-Congress governments were elected in several states; and after the Emergency. It also happened after the NDA’s Shining India campaign in 2004. Past elections have shown that efforts to manipulate the vote do not always succeed. Given sufficient motivation, the citizenry has thrown out unpopular governments.

After 1945, global security was contaminated by the Cold War. The non-communist bloc was dominated by the Western alliance, whose commitment to democracy was contingent upon convenience: it consistently used authoritarianism and ethnic divisiveness for imperial advantage. Hence the American support to undemocratic regimes in South Korea, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia and Iran. Of the newly independent states, Indonesia succumbed to authoritarianism and then a US-backed military dictatorship. Its first democratic presidential election took place in 2004. China inscribed single-party rule into its constitution – its rulers remain fearful of democratic freedoms. Sri Lanka’s elite engaged in a competitive sectarianism that targeted Tamils and resulted in civil war. Two states were founded upon religiously defined nationalism: Pakistan and Israel. These unstable entities have become the vortex of global conflict. Today, the world watches while Israel explodes and Pakistan implodes. A democracy is characterised not only by free elections, but also in terms of whom it defines as the ‘demos’, or people. The application of exclusionist principles in the very foundations of a state is a recipe for disintegration.

The stamina of Indian democracy derives from its inclusive and secular principles. The burning issues of our times are global, not national in their scope. Nation-states matter only in the manner of the examples they present, of political norms that stand the test of time. The preservation of India’s democratic freedoms, tolerant values and its rule of law matter a great deal to the world, provided these are upheld without arrogance. South Asia has become the arena of far-reaching geopolitical changes. Western policy towards the region continues to be driven by pragmatism rather than principle. Facing the oncoming challenges will be easier if the Indian Union remains true to its foundational ideals. The coming elections carry greater significance than our leaders appear to realise.

Featured Image Credits: Edex Live