Humanity in diversity: Can it really exist?

Very serious thoughts about human nature and diversity emerged in my mind after the recent protests by the JNU students. The subsequent – and completely unrelated – questions raised by the news media on the significance and utility of the education being imparted at JNU was intriguing. I wondered what it was that made a group of people from a particular background – including educational, political, economic, religious, racial, and gender-based – to strongly denunciate people different from themselves. That rather than indulging in conversation, understanding, and resolving conflicts on a personal, individual level, there stands one community/ group making unevidenced claims against another. In this case, people from a different educational background questioned the value of education at JNU.

On pondering deeply over this example, I found a commonality in every current or historical event – a strong tendency to stereotype, question, and blame the beliefs, actions, and interests of entire communities/ethnic groups – under the various social, political, economic and cultural contexts. Throughout all the history and in our daily lives, we all seem to strive for the company of people like us, whom we can relate to (1).

Not only that, we find it difficult to ‘adjust’ with anyone significantly different from us, either by choice or by descent. We live in a diverse world and country. Yet, we always tend to create microcosms of homogeneous communities and groups for individual, socio-cultural, and political purposes. And among all the conversations about diversity, there still exists the very instinctive sense of finding similarities in another person’s thoughts, experiences, interests, to enhance the likeliness of friendship and cohabitation (1,2).

This comes from the generalization of the inherent character of a person belonging to a particular school of thought/background. And this naturally occurring ability to stereotype has, in the past and present, become a reason for a multitude of large scale exploitation with serious repercussions. Nothing else is a better example of this than the Holocaust. Only because anti-semitism had existed long before Hitler, it became possible to convert it into a full-fledged Jew removal campaign after the Treaty of Versailles.

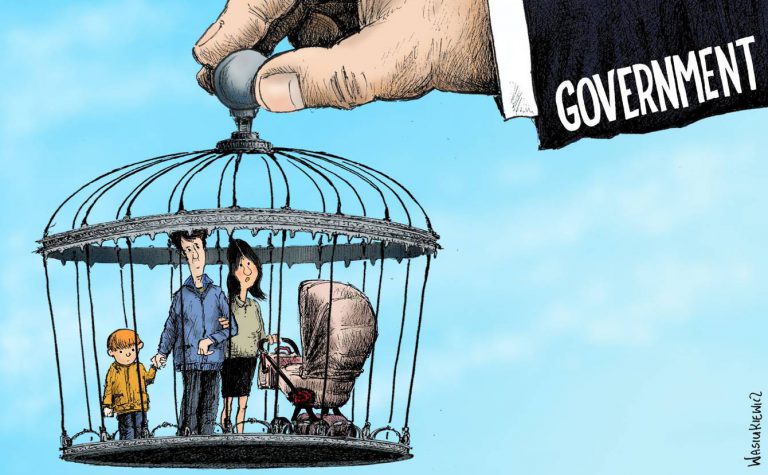

Based on the correlations among a variety of prevailing social, economic, and political inclinations in a country and the world, the natural human characteristic to form homogeneous groups can quickly be mobilized to act against the interests of another, to convert or alter them (2) violently. In such polarized environments, humane feelings for one another, as human beings, mostly lose their significance. They merely reduce to a self-preservation quality — mostly extending only to individuals of the same group. Thus, even though the individual natural tendency wishes to attain homogeneity, it becomes imperative to identify the conditions which can reconcile humanity and heterogeneity for peaceful coexistence.

Examples of heterogeneous unrest

The dislike towards differences in interests and beliefs on both individual and community level might be natural, but this doesn’t always turn into a threatening, aggressive atmosphere. To identify this kind of unrest that heterogeneity can invite under various different normative contexts, and to draw some of their essential characteristics, I will use a variety of examples of aggressive unacceptance. These examples will show how stereotyping is often a reason for irrational collective blaming, leading to a controlled extension of one’s humanity.

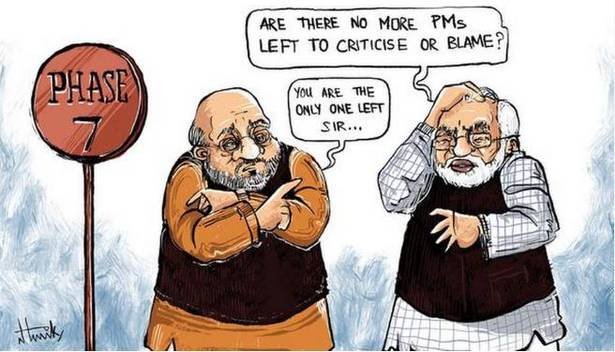

In India, the election campaigns and the various policies as a result of the last two general elections, are sound examples of supporting one religious community over another. And these aren’t just political acts, but highly supported political acts. Acts that have garnered lots of votes. Spewing hatred and sidelining entire communities from their political, social, and economic rights systemically is our day’s spectacle. Donald Trump, too, acquired a lot of votes based on his xenophobic ideals. His tweeting pattern shows that he believes all of Islam (anywhere in the world) is a threat to the United States (3). There is no logic in declaring an entire religious group, composed of millions of people spread across the globe, as a threat only because they are connected by religious tradition. Yet, collective blaming, victimization, and retribution happens and is an acceptable norm everywhere (2).

Interestingly, the #metoo movement regarding the women’s sexual abuse happened recently on the Internet, exhibiting a very nuanced irony in how the expression of discrimination was interpreted as collective blame. When the movement started, a parallel #notallmen started too. Although it stated a logical and undeniable fact, which is that not all men are perpetrators, but the twist here was that it aimed to halt the #metoo movement and the empowerment it gave women (4).

After years of repression, when women were speaking about their experiences, it became a threat to our overall masculine societies. And then the very logical claim #notallmen reduced to smarm – exhibiting diversity by aiming to curb its very means. Such examples are worth mentioning when they can be exploited to mean what they do not, effectively showing us the importance of being given to self-preservation over collective acceptance and compassion.

Furthermore, a few months ago, I read an article where a BJP leader said that Muslims in India were reproducing more to become the country’s majority. And this opinion gained so much popularity that the projection of the Muslim population over 20 years became a highly forwarded WhatsApp message. Not being able to believe this, I contemplated how a regular family planning conversation in a Muslim household would look like if this were true –

“Let’s have another child, honey. We only have 7 now… How will we take over the country with this number? I need to answer to my community!”

“But how will we feed, clothe, and educate them?”

(Silence)

Obviously, this looks ridiculous and is an absurd claim, as well. The National Family and Health Survey (NFHS) 2015-16 data compared with 2005-06 NFHS data show that the reduction in fertility gap between Hindus and Muslims by 7% was due to different contraception patterns, poverty, and levels of sexual education (5). Yet, the number of children per Muslim woman had reduced from 3.4 in 2005-06 to 2.6 in 2015-16 (5).

Furthermore, even when the Muslim population peaks, 4 out of 5 Indians will still be Hindus (6), and no more than 18.4% of Indians will be Muslims by 2050, from 14.4% in 2011 (7). This shows that when we look at a particular community with generalized feelings or opinions, we lose the sense of humanizing their individual existence. That their growth becomes a source of insecurity, hampering the means to preserve a group’s beliefs, interests, and resources.

Another example that I recently came across was when students in Rajasthan University beat up Kashmiri students, claiming that they were all terrorists. Again, this comes as no surprise after Banaras Hindu University students protested against a Muslim professor teaching Sanskrit. From generalizing to stereotyping to communal violence, we have all these examples illuminating the issues that a diverse set of people bring about. They just do not get along, neither do their natural instincts want them to. But to seek peace, we aspire to replace this inherent sense of self-preservation with what we assume to be humane values.

In retrospect, the question arises on what being humane even means. And why a certain counter-intuitiveness – in the intuitive aspect of preservation of one’s own beliefs and interests – is considered essential for humanity. To answer this, Annie Dillard’s The Wreck of Time (8) becomes a perfect preface. She opens and ends with overwhelming pages full of statistics on people who have suffered and died, are suffering and dying. She intends to show us that the numbers that fail to foster any emotions in us actually depict real people. It is assumed that with this realization, one would feel that they’ve been hit hard. An assumption that they are able to value compassion and empathy enough to feel those feelings, knowing that this is the essence of being human.

The emergence of the much needed humane values

Human beings have a recursive thinking capability, which, among other things, means that they can think and feel more than just about themselves through various orders of thinking (9). A first-order thinking capability assures that one can think about themselves, to support their survival through limited resources, and can preserve their life. But when the higher orders of thinking and feeling come in, one gets the ability to think like, and about others – the transactional effects of their actions on themselves and others. And with even higher levels, one can feel how other people/species may feel (9). But as far as recursion goes, only being able to feel how others may feel does not ensure humane feelings and actions.

With all the possibilities that our existence in human form has given us, we tend to pride ourselves in higher-order thinking such that we can preserve not only ourselves but also our communities. In these situations, most other communities and groups are the enemies or competitors for resources. However, with the same recursive thinking, humanity seeks to extend to the entire human race when the threats are apocalyptic and external. In that, an obligation to value various human possibilities and diversity emerges, making the moral and ethical frameworks of the social dynamic and important parts of our existence. This explains why, only with time, we realize why individual acts that were always inhuman were not considered so by the dominant group(s) (such as slavery, marital rape, LGBTQ repression, etc.); leading to a very dynamic philosophical history of morality in society and politics (10, 11). And even the need to have a dynamic moral philosophy indicates that education in morality is necessary to envisage compassion, which everyone may or may not necessarily feel on their own (12).

Reconciliation of humanity with diversity

With this, I believe we have entered a new age. An age where, with the existence of nuclear weapons and climate change, we are sensitized enough to identify the ills that can lead to our destruction as a race. And in this age, with the peaking sensitivity of our emotions, humane values have not only become necessary but have transitioned into pragmatic morality from just being religious/spiritual morality (13). That now, before duty, happiness, self-satisfaction, and preservation must come compassion and empathy for each and every living being, taking us into a spiritual dimension. And that might be one of the reasons we have made it our dynamic mission to accept diversity. To learn from various perspectives, thoughts and experiences will now fuel our emotional sensitivity towards more exploration of conscious action, leading into a glimpse of perpetual peace on the edge of potentially destructive future.

The anticipation of an apocalypse, among other things, has thus given us the most nascent opportunity to extend our humanity towards a much more diverse population.

P.S.- I personally believe that every human being’s natural state is of being compassionate and empathetic. That they want to love only for the sake of loving and feeling the beauty of it, the beauty in uniqueness and various possibilities of being human, the inner beauty of life, and our very own existence in this cosmos. That is because I experience these feelings personally. But I have no sufficient examples to prove its universality. Thus this article is to make a rational argument.

This article is another side of how I think in a way I wouldn’t want to. A struggle between wanting to be rational & skeptical vs. just wanting to surrender to belief in humanity. Maybe one day, I will learn to balance both or will have the wisdom to choose one.

References

- http://conf.som.yale.edu/obsummer07/PaperBen-NerKramer.pdf

- Lickel, Brian, et al. “Vicarious retribution: The role of collective blame in intergroup aggression.” Personality and Social Psychology Review 10.4 (2006): 372-390.

- https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/11/30/16645024/collective-blame-psychology-muslim

- https://slate.com/technology/2014/05/not-all-men-how-discussing-womens-issues-gets-derailed.html

- https://www.livemint.com/news/india/what-a-narrowing-hindu-muslim-fertility-gap-tells-us-1550686404387.html

- https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/5bsICkXvl4t4hXSewk8bkN/Four-out-of-five-Indians-will-still-be-Hindu-even-when-Musli.html

- https://www.firstpost.com/india/bjp-leaders-cite-growing-muslim-population-as-threat-to-india-facts-dont-back-their-claims-4303403.html

- https://harpers.org/archive/1998/01/the-wreck-of-time/

- https://www.americanscientist.org/article/the-uniqueness-of-human-recursive-thinking

- Solomon, Robert C., et al. Introducing Philosophy: A Text with Integrated Readings. Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Batson, C. D., Chang, J., Orr, R., & Rowland, J. (2002). Empathy, attitudes, and action: Can feeling for a member of a stigmatized group motivate one to help the group? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(12), 1656-1666.

- Escola, Casey A., “Teaching empathy, uncovering the need for greater emotional and social learning in early childhood education”. New York University

- Baier, Annette C. “The need for more than justice.” Canadian Journal of Philosophy 17.sup1 (1987): 41-56.

Featured Image Credits: Azra Bhagat

Readers' Reviews (3 replies)