How much fee should JNU students pay?

Srinath is the Founding Editor of The ArmChair Journal. Currently at the University of Chicago, he is also an alumnus of IIT Madras, Ashoka University, Rishihood University and Purdue University.

Needless to introduce either JNU, or the recent protests by students that have been happening about fee hike.

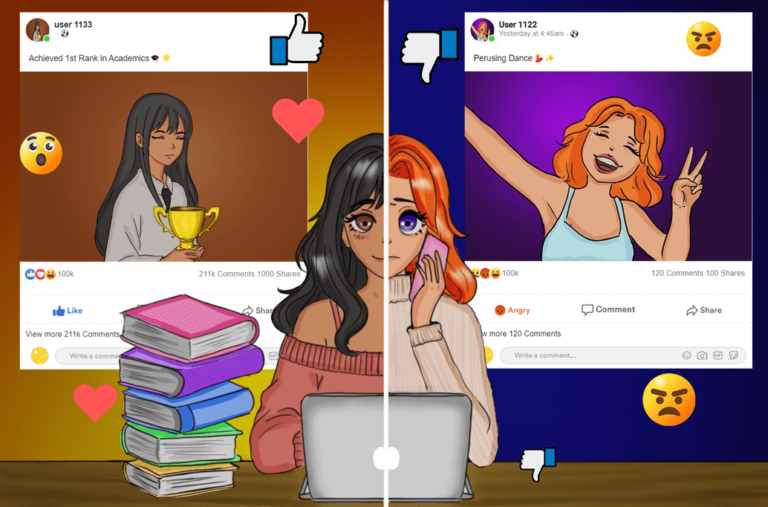

There will not be much dispute if one says India is an opportunity-scarce society. Meaning, there is a substantial amount of its population living in poverty, it observes exponentially rising inequality, and there are social barriers like class, caste, and gender, which are a hindrance to equality of opportunity. Equality of opportunity is required so that an equal platform for everyone is realized. Such a platform is expected to bring in resource distribution, which is fair and just.

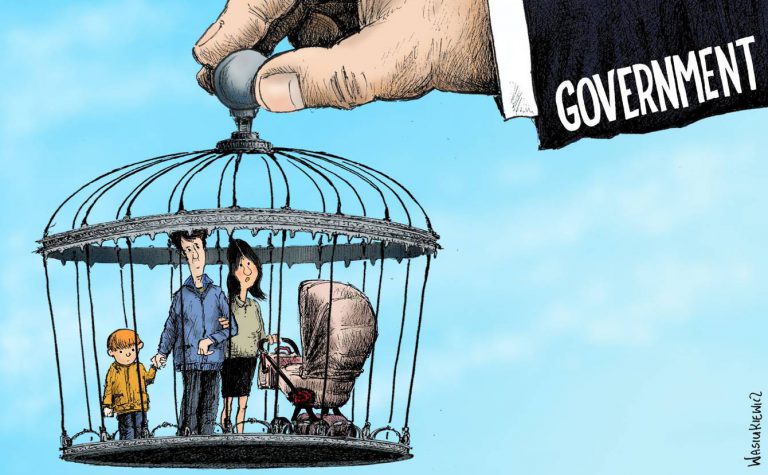

To realize equality of opportunity is an ideal enshrined in the preamble of the Indian constitution too. In practice, the Indian state tries to realize this goal through its ideals like social democracy and the welfare state. In tandem, it also focuses on economic growth or creating wealth, with an expectation that it would lift people out of poverty.

This makes health and education as the focus areas of the state. Health so that everyone deserves an opportunity to avoid avoidable suffering. Education, so that everyone is equipped with the tools to compete and claim their worth. Denial of education denies the required skills to people, thereby denying them equality of opportunity. As such, education is a tool of social mobility that raises the level of individuals to compete to claim resources, and so that the higher talent is justly rewarded.

However, there are also structural factors that always distort the platform as much as the state tries to level it, if not higher. If the Indian state has been trying to fix the platform for over 70 years, why does the inequality keep increasing after all? It tells that either the state is inefficient if it has the required capacity, or it is too powerless to realize this level in practice. It could also be both.

In any case, all it appears to be doing at least is to decrease the pace of rising inequality. It would be counter-intuitive to say it might actually be increasing the speed of increasing inequality with its free hand to free markets. After all, neoliberalism dictates the world as of now, and the state facilitates markets that have always been known to increase economic inequality.

It must be acknowledged that efforts of the state have led to an increase in the prosperity of the country, measured through GDP every year. Poverty has also been mitigated. Even when neoliberalism can bring people out of poverty, should it make the situation of equality of opportunity worse? Aren’t opportunity and inequality interlinked? Definitely, the question is more complex, and the framing might itself be contested. In fact, hypothetically, even when there is no poverty, inequality of opportunity can hinder what one can realize. Hence, it is a problem that can’t be avoided. More so, when there is poverty.

Nevertheless, within the framework of equality of opportunity, education deserves attention. With opportunities available after education, social mobility is expected to enhance one’s dignity and development. Whether education can counter the distortion of structural barriers like class, caste and gender may be contested. But education at least empowers us to have better opportunities compared to our own peers in terms of socio-economic backgrounds, within the existing societal structures.

Hence, it is a reasonable expectation from the state to make the situation towards this possible. A government like ours is always a resource-scarce in a society which is also an opportunity-scarce. Education comes at a cost, and spending on education could mean to divert resources from other equally competing goals of the state. Hence, to realize the goals of equal opportunity, it is imperative to call for support from non-state possibilities.

These non-state possibilities could take different forms. Let us assume all educational entities at all levels are non-profit, both in letter and spirit. It is here that a discussion on education becomes interesting. Whether we privatize it or keep it public, or a mix of both, the goal is to be able to provide high-quality education to all possible. Such an education is a prerequisite to building an equal and fair platform for everyone to compete.

Sometimes, the government funds this education through taxes collected. One way of raising funds for all non-profit educational entities is through charging fees from students for instructional services rendered. Another way is through philanthropic partners, along with charging fees. Needless to mention that when education is charged, only those who can afford it can pay. Philanthropy ensures that those who cannot afford the high fees can join universities with scholarships. As such, inequality of wealth comes into play. Philanthropy and government subsidies help students who cannot afford an education at these levels.

The vital aspect to be noticed in the case of public institutions is that the fees charged are also supplemented by scholarships. Depending on the institute, the fee charged is sometimes nominal, like the case of Jawaharlal Nehru University, or the University of Hyderabad, and sometimes reasonably high in the case of Indian Institutes of Technology.

Private deemed universities, on the other hand, like the Vellore Institute of Technology, charge humongous amounts as annual fees. Private institutions backed by philanthropy like the Ashoka University have prices on par with all private institutions, while also having the advantage of funding students who cannot afford these humongous costs of education. Let’s deliberately leave different other private colleges which are affiliated to public universities, for the sake of simplicity to explore the topic.

It is not all about the cost of providing education

In light of the ongoing JNU protests, I would like to highlight several features that make the issue more than about money. I studied at a central public university similar to JNU, University of Hyderabad (UoH), and also at IIT Madras. I always realized that the food and hostel qualities are poor at the UoH, without much infrastructure available for students. The hygiene in hostel premises is also not great. Food in the hostel messes is basic, lacks variety, and quality. The classroom infrastructure and auditoriums also appeared poor.

I used to wonder why the institute does not charge more from students and improve the facilities. After all, that was how IIT Madras manages to provide better mess facilities. Further, UoH also did not appear to subsidize food anyway. Students were charged every month based on expenses incurred. Why can’t they simply raise the quality of food through increasing mess bills?

I realize they do not have such a luxury to increase the cost of living of students for many reasons, esp. when compared to IITs.

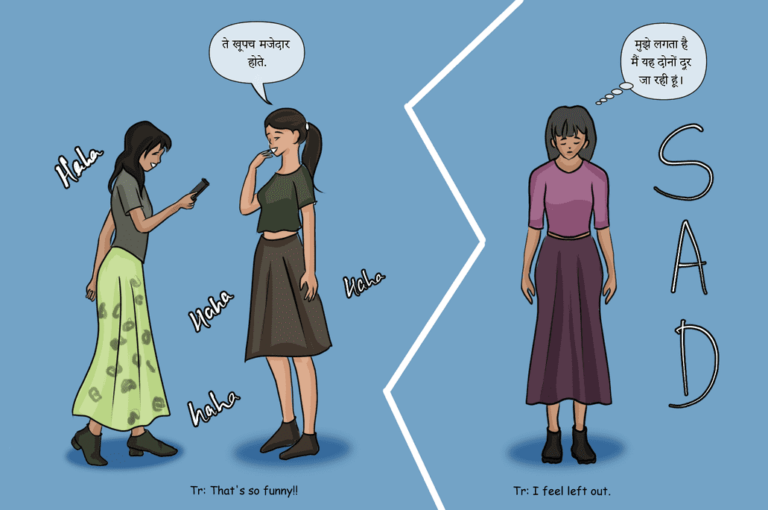

- Someone who visits an IIT versus a central university focussed in arts and social sciences understands that students at IITs appear wealthier in general. Though I have not done a survey, we could argue that most of the students enter IITs after paying large amounts of money for coaching centers- which acts as a financial filter. This is not the case with universities that focus on arts and social sciences.

- Despite having higher fees, students of IITs are promised a reasonably well-paying job after they graduate. This makes them look at their education at IIT as an investment. Due to the lack of reasonable placements at arts universities, these students cannot look at education as an investment.

- Students of IITs are trained for the markets, while students at arts are little detached from markets. This makes the alumni of IITs financially powerful enough to give back to their alma mater, while the alumni of arts universities mostly struggle for a decent life on the periphery of markets.

Another significant difference that deserves attention is the nature of the difference in the way they approach knowledge. In social sciences, a large part of the endeavor is to critically analyze the way society is generally understood and prescribe reforms to improving it. It is inevitable that this inquiry can challenge the existing establishment. However, in the field of engineering, most of the knowledge is ‘material,’ which takes the social structures for granted or at max, displays indifference, and aims to improve lives through technology or innovations. The change is targeted towards material well-being rather than social relations and structures.

As such, the establishment in power is bound to be questioned by students of social sciences. This is a trait that keeps the society dynamic and makes it critical- a hallmark of any democracy. A democracy without dynamic critical thinking is no democracy. That is why it is essential for the taxpayers, as citizens, to nurture these centers of critical thinking. An uncritical society is the breeding ground for authoritarianism. To stop funding for these universities means to cut the lifelines of critical thinking.

Hence, not all public universities in India are the same, and they must be treated differently as such. This distinction warrants that arts focussed public universities require more assistance from the government vis a vis charging fee from students.

However, the only question is: What are the appropriate minimum fees that we can charge in non-technological universities, to realize the goal of equal opportunity? Whether it is the government or philanthropy, someone must bear these costs. Can philanthropy replace government funding?

The author is the founding editor of The ArmChair Journal. This article will soon be followed by another, which tries to explore philanthropy in education.

All Image Credits: Sri Harsha Dantuluri

Readers' Reviews (4 replies)