Catch-22 of a pandemic: Inception of a disciplined majority

This is a guest post by the authors. Pls email to [email protected] if you want to publish an article.

Pandemic, like history, repeats itself.

It is significant to historicize pandemics because it lays bare the fact that the only lesson humankind has learned from history is that it hardly learns from history. An attempt to trace the historiography of pandemics and governments’ response to such phenomenon, will reveal two pervasive themes: disciplined majority and technological intervention. These two factors act symbiotically to strengthen surveillance.

India is a pompously populous country. The rhetoric of social distancing is, therefore, pervasive in the Indian government’s prescription to stall the viral spread of novel coronavirus. Home quarantine has also been advised to ‘tens and thousands of people.’ People who have flown in from overseas countries are also being compulsorily quarantined. In addition, travel from and to India has been temporarily stalled. These measures, which are apparently innocuous and beneficial, facilitate disciplining society.

The tactic of fixating individuals to spatially segregated arenas, which GoI has adopted, is being reinforced by the pervasive use of technology. For example, the Karnataka government has launched an app called Quarantine Watch to keep track of those people whom it has put under home quarantine as suspected carriers of COVID-19. The Aarogya Setu app has been launched by the GoI ‘to connect essential health services with the people of India.’ These apps deploy ‘health surveillance’ to curb the curve of COVID-19.

Deploying surveillance in times of pandemics is not new. Its historical echoes can be easily heard. A critical analysis of government measures aimed at curbing a plague outbreak in seventeenth-century Europe unveils a systematic deployment of surveillance. Programs of strict spatial segregation, ‘lockdown’ of the town, and quarantine were adopted by the government to confront and combust the plague. These programs discipline the society, much to the government’s favor and fervor. This has been recorded by Foucault in ‘Discipline and Punish The Birth of the Prison.’ Disciplining designs, according to him, strengthens both state power and the government’s grip over demos.

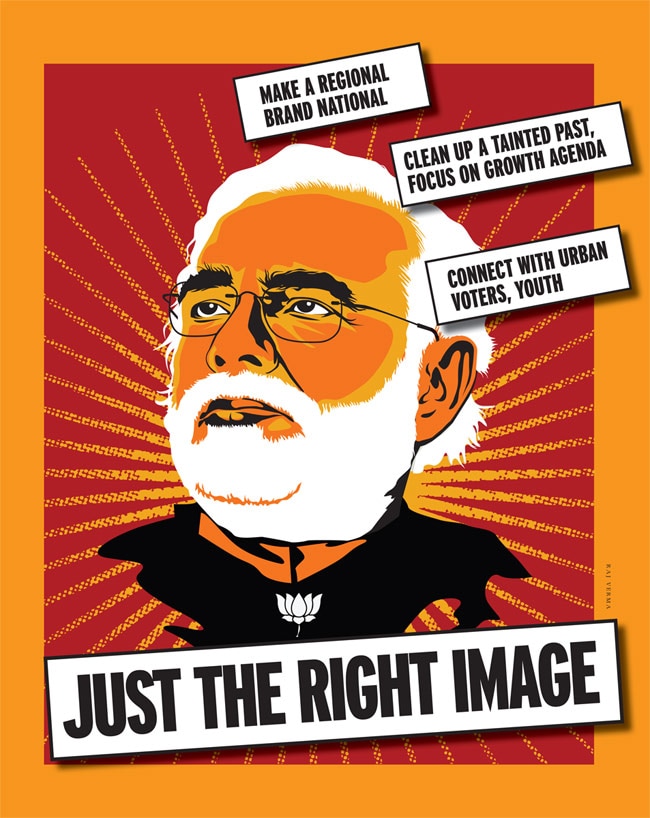

In 2020, panic and paranoia are running thick through India. Between the power of the virus and the power of the state has grown an ambivalence. This has prompted the government to don the ethical hat of a ‘caregiver’ to rescue its populace from the crippling uncertainty that has ensued. To that end, it is mobilizing its power against the virus through policies that aim at disciplining men. The pandemic is a situation of medical and not strategic uncertainty. By using the rhetoric of ‘war’ to ‘fight against the threat of Coronavirus,’ the government has successfully militarized the pandemic. Exceptional circumstances breed exceptional measures. Disciplinary actions are vital in winning war; this ‘war’ too, is no exception.

Nurturing discipline

Caught in the binary of life and death and confronted by a state of exception hitherto unknown, Indian people have accepted the government’s attempts at disciplining them. They have lauded government efforts of spatial apportioning. The decision to impose a country-wide lockdown within a concise notice period has leveraged public support. Meanwhile, Indian citizens have bypassed the plight of the internal migrants as collateral damage of this ‘war’ rather than a consequence of governmental mismanagement. The ‘habit’ of ‘social distancing’ has been successfully inculcated as ‘most’ Indians are strictly upholding distancing rules in public places.

In addition, Indians have massively responded to seemingly unscientific calls of blowing conch shells, clapping or ringing bells or putting off light for 9 minutes at 9 pm on a particular day as a gesture of fighting the ‘evil’ virus and praising the efforts of health professionals in fighting the menace. This series of events indicate fruitful implantation of discipline in the face of uncertainty and germination of a disciplined majority with little impact on the disease curve.

Disciplining in times of ‘war’ does not require deliberation. Wars wane, but disciplinary regimes imposed by governments continue to chain.

Disciplinary power of government gets reinforced by technological interventions that lapse into surveillance if left unchecked.

In the seventeenth century, the proclaimed ownership of scientific know-hows enabled governments to deploy disciplining, and even inhuman, measures on ‘less knowledgeable’ citizens. Four hundred years later, technologies embody and disseminate scientific know-how. En masse deployment of technological interventions enables ‘under-the-skin surveillance.’ Harari has made references to how the state of Israel, in its fight against coronavirus, has deployed technologies ‘ generally reserved for battling terrorists’. During the later stages of the Ebola (2014-2016) outbreak, GPS coordinates and text messages were used to ‘report syndromic surveillance data’ in certain countries. Surveillance is intimidating because it helps in the regeneration of power. It is also a covert breach of privacy veiled under overt promises of protection.

Digital surveillance

Central and state governments in India have taken recourse to digital surveillance to fight the ‘war’ against COVID-19. The app, Quarantine Watch, follows movements of people who have been home quarantined using GPS technology and requires them to submit hourly selfies as proof of them staying indoors. This application has paved the way for the government to enter into the private spaces of ‘suspect’ COVID-19 bearers, thereby levying consent to surveillance. App permission also requires access to storage, the rationale behind which remains unclear.

The Aarogya Setu app is designed for large-scale usage. Its primary purpose is to aid situational awareness in contact-tracing. It initially asks for name, phone number, age, sex, occupation, and a month’s international travel record. The app seeks permission to use location sharing, Bluetooth, and GPS to ‘protect’ the user. Data, so gathered, is stored in a central server which authorities can access. The initial input, which connects mobile number with ascriptive identities of users opens up ways for profiling by the police, if they will. This remains a possibility during the pandemic and also after its demise as there is no explicit guarantee of complete data deletion. Also, the uninstallation of the app may not amount to data deletion. Personal details will be retained until the user deletes the account or asks for its removal. Though the data is saved with a Digital ID and names of persons are not explicitly used, it can be tallied with public data to reveal individual identity. Modern technology of database linking facilitates such moves.

Additionally, there is no expiry date of the aggregated data and its usage. Though exact data can only be removed after 30 days of formal deletion of the user account, there is no specification about the expiry of aggregated data or inferred patterns. Information regarding the location of the server and people responsible for its design and maintenance have also not been made public. In the backend settings, the app accesses contacts and phone calls, the utility of which is unclear in relation to its avowed objectives.

Curiously, the Indian army has directed its personnel to abstain from using this app in ‘office premises, operation areas and sensitive locations’ and to ‘switch off location services and Bluetooth while visiting public places.’ It has further said that the contact list of users should not contain any reference to their “rank, appointment, or service.” Articulations of ambiguity by the army regarding the app is noteworthy. The promise of protection is promiscuous because under its garb, ‘health surveillance’ has chances of slipping surreptitiously into ‘mass surveillance.’

A ground that breeds disciplined majority

Harari rightly notes that if people are given a choice between privacy and health, they generally prioritize health. The Indian experience confirms his exposition.

Quarantine Watch and Aarogya Setu have been downloaded by more than 10,000 and 10 million people, respectively. This not only underscores an ignorance towards privacy as a fundamental right but also hints at the growing fetish of data nationalism. ‘India’s data for India’s development’ has become the mainstay under the incumbent government. Going by the number of downloads, it can be speculated that Indians, too, are comfortable with the national government handling their data. Trusting the government with such a huge amount of personal data hints at the birth of a disciplined majority. The blitzkrieg against the pandemic is being fought on the terrain of individual information and mass discipline. War-making has helped modern governments to consolidate their national aspirations. The use of military language to tackle the pandemic simply reinforces the statist project. The deployment of disciplinary tactics and the employment of the trope of protection has enabled the incumbent dispensation to consolidate and intensify its power. Historically, statism has reared suffering.

Pandemic is provisional, statism steamrolls.

This pandemic is a portal to a new world—the nature of newness matters. Black Death in fourteenth-century Europe led to more centralized states. The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 also consolidated statist power in Europe and America. Economic depressions which follow a pandemic becomes an alibi to entrench statism further. The danger lies in history’s habit of rhyming. Although it is too early to comment on the repercussions that this pandemic will have on statecraft in India, caution should be exercised already. Discipline, coupled with surveillance, is the springtime of statism. It is time that Indians reflect on the questions which pervade the pandemic: should we passively witness the birth of a disciplined majority or “Mother should I trust the government?”

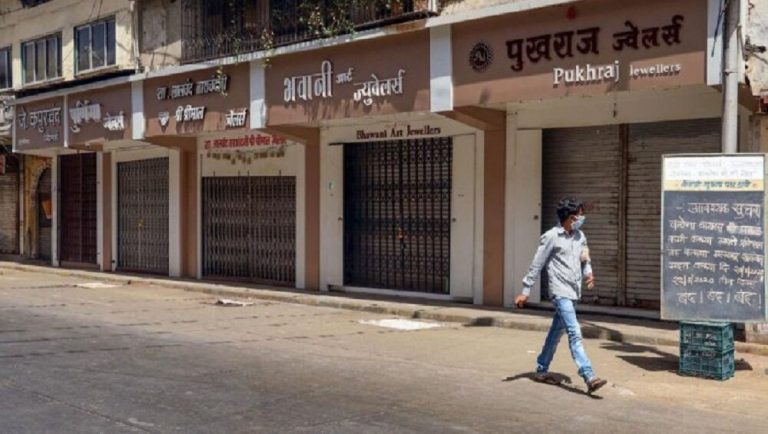

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

Authors:

Shamayita Sen is pursuing her MPhil. in Social Sciences at the Centre For Studies in Social Sciences Calcutta. Her area of interest includes subaltern studies, social movements and collective memory.

Debabrota Basu is a researcher based at Chalmers University of Technology, Sweden and is a visiting researcher at Harvard University, USA. His work focusses on the privacy and ethics of AI.

A much required analysis of the Aarogya Setu app, which has troubled me ever since National Testing Agency sent me an unsoliticed email urging me to download the app as soon as possible, as an immunization measure against the virus. The only thing it’s immunizing me against is complete privacy and protection of my data from the GoI.

It is interesting to note that with the Census 2021 activities disrupted due to the ongoing crisis, the government has jumped the obstacle of the NPR-induced panic, and all efforts on the part of rights-bearing citizen subjects to stay vigilant and refuse to share their personal details, by making information regarding one’s whereabouts on one level mandatory, and on another, the only conscientious thing to do. Homes have now been added to the Foucauldian directory of the prison, school and clinic. This essential curb on the freedom of movement incurred by the general public will also make important inroads into the deployment of population profiling incumbent to the sort of exclusionary citizenship this state wishes to carry out. Digital surveillance acts as the perfect panopticon by steamrolling over inconsistencies in information by turning each individual into a perfectly quantifiable unit in the algorithm. The Aadhar biometric exercise, which followed the now too-artefactual, almost archaic system of individual ID cards, seems terribly outdated and ineffectual in a world where thermal scans, drone surveillance, innoculation biometric, geotagging are the norm and protocol. Big data, big brother, and big pharma have joined hands for a massive takeover, the effects of which we have only begun to see. Conspiracy theorists do not seem as crazy now as they did to us in the past, for their long held paranoias about the Gates and Rockefeller foundations microchipping Texans like milch through vaccinations. Somewhere, we all harbour this fear of our data-hungry governments now.