Travelling to Delhi, taking a 12th century traveller along

“Here and there in every mohallah, the mosques raise their heads towards the sky, their domes spread out like the white breasts of a woman bared, as it were, to catch the starlight on their surfaces, and the minarets point to heaven, indicating, as it were, that God is all-high and one.”

Ahmed Ali wrote these romantic lines on Delhi, painting an idyllic image of the city, in his 1940 novel ‘Twilight in Delhi’. This was the city of lived dreams for countless poets. Many a writer lauded this place as Jannat. Someone called it Jahanpanah – the refuge of the world, a phrase reserved for Sultans and their like. When I read lines like these that blossomed out of pages, I had wanted to penetrate into this fantasy.

To assist me in this venture, I sought the help of William Dalrymple’s pen. As I settled on the train that brought me to the city, I grabbed my kindle out to read the book ‘City of Djinns.” I was the loyal and passionate audience and reader that Dalrymple had written the book for. I watched with awe as the seven cities of Delhi unfolded before me. From the palace on the Raisina Hill to BB Lal’s excavations in Purana Qila – the city seemed like a Kathasaritsagara, an ‘ocean of the streams of stories’ to me. By the time I reached the end of the book, I knew that this was not going to be enough. If Dalrymple was insufficient, who could lead me? I looked for the answer to that question back in his book. And there it was. Ibn Battuta.

Describing the arrival of Ibn Battuta, Darlymple dramatically wrote:

During the sweltering Id of 1333, a camel caravan could be seen winding its way through the narrow passes and defiles of the Hindu Kush. On the principal camel sat an irascible Muslim judge. He had been traveling for eight years and was now heading south towards Delhi, the capital of the Sultan of Hindustan.

It is almost as if someone whose advent had been awaited was finally here. Like the prophet in the film ‘The Message’ and Peter o Toole in ‘Lawrence of Arabia’, Ibn Battuta in Dalrymple is a semi-hero.

When one follows Ibn Battuta there are not many places to explore in Delhi, for the simple reason that substantial sections of the city rose to the sky after him, slowly even swallowing older layers. In Battuta’s times, it was the regime of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq and the era of Jahanpanah, the fourth city of Delhi. The walls of the recent cities were very young.

With a fine sense of history, Ibn Battuta says:

The city of Dihli is of vast extent and population and made up now of four neighboring and contiguous towns. One of them is the city called by this name, Dihli; it is the old city built by the infidels and captured in the year 584 (AD 1188). The second is called Siri. The third is called Tughluqabad, after its founder, the Sultan Tughluq, the father of the Sultan of India to whose court we came.

The first place that interests him is the Jama Masjid (that the Archeological Survey of India calls in its brochures ‘Quwwat-ul-Islam’) in today’s Mehrauli. ‘How little things have changed?’ I told myself. Perhaps owing to the metro station in proximity, this spot continues to attract tourists. It is amusing to the thick hordes of people who often arrive in groups. The unusual is ignored as family photos take precedence. Couples lean on the authentically Hindu pillars that hold up the mosque’s roof.

The mosque was built by Qutubuddin Aibak, the first Sultan of Delhi after having captured a Hindu temple that stood in its place. The members – pillars, cornices were reused. Unsurprisingly, the Adhai din ka Jhonpra mosque in Ajmer, also a point that Aibak touched during his general-hood under Muhammad of Ghor, resembles this Masjid in a great way. Historians conjecture that an idol housed in the National Museum today perhaps belonged to this Jama Masjid. Is the conquest of the temple an act of religion or one by politics? Or some say, a case where a conqueror simply economized? But one thing is sure; it is a historic mosaic. The mosque is like a bark of a tree or the skin of an onion. We see layers of history imposing one over the other. Ibn Battuta, removed by seven centuries from us, had other questions running in his mind: How was this built? How could this be so utterly different from all that I have seen?

He says:

The cathedral mosque occupies a vast area; its walls, roof, and paving are all constructed of white stones, admirably squared and firmly cemented with lead. There is no wood in it all. It has thirteen domes of stone, the mimbar also is of stone, and it has four courts.

The image of one building rises high above the ebb of the mosque: Qutub Minar. While the whole complex is perfect and exemplary, the Minar is more than all that.

The Minar was started during the reign of Qutubuddin Aibak and was completed during Iltutmish’s years. Some speculate that the mosque was to complement the Minar, but that is an arena of its own. Ibn Battuta could not contain himself, gazing at it, and my words fail me. These words have endured:

In the northern court of the mosque is the minaret, which has no parallel in the lands of Islam. It is made of red stone, unlike the stone used for the rest of the mosque, which is white, and the stones of the minaret are decoratively carved. The minaret itself is of great height; the ball on top of it is glistening white marble, and its apples are of pure gold.

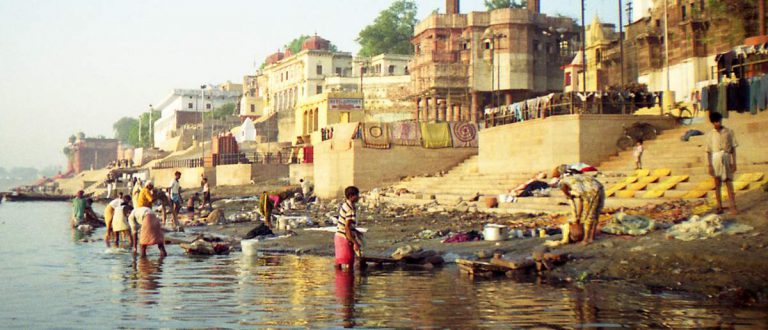

Battuta’s next destination was, to me, not a destination at all. I stumbled upon what looked like the walls of a fort when I visited a park – Deer Park, it is called – in Hauz Khas, an affluent locality in the city. The park was lush in its own right, hosting lakeside cafes and bars. It buzzed with families who had come to picnic and couples who had made time for a rendezvous. Some young boys demanded a stake in the land for a fun game of football while outside, buildings and roads were encroaching into peaceful commons. There were sights of people playing guitars, doing aerobics, and practicing Yoga. But there was also the tank.

The lake in the park was enclosed by the walls of a tank that lent its name to the locality ‘Hauz Khas’ (royal tank). a tank was begun under Iltutmish (called by Battuta as Lalmish), but the tank that acts as the water reservoir today was excavated under a later king Alauddin Khilji.

When the reservoir is filled with water, it can be reached only in boats. But when the water is low, the people go into it. Inside it is a mosque, and at most times, it is occupied by poor brethren devoted to the service of God and placing their trust in Him. When the water dries up at the sides of this reservoir, they plant sugar canes, gherkins, cucumbers, and green and yellow melons there.

The experience in the deer park was revealing. There is not a great deal written outside the park advertising the 800-year-old monument inside. But perhaps, there was no need for that. To people frequenting the park, the monument was commonplace. It was just another feature of everyday life. This stands out: the mundane nature of history in our life. In this city of Delhi, remains of the past are ubiquitous and are subjected to neglect, sometimes benign but very often, pathetic.

In the localities of Hauz Khas and Mehrauli, ruins of walls from Qila Rai Pithora, Siri, and Jahanpanah make surprising appearances: in the middle of roads in Universities, behind malls and around busy residential areas. These were the walls that Battuta called “unparalleled”.

As has been said, these cities of Delhi are either mostly dead or dwell in new forms. However, the city that has survived belonged not to Muhammad Tughluq but his father, Ghiyath-Uddin or Ghiyasuddin. Battuta visited this fort too. Unlike Mehrauli and Hauz Khas, Tughluqabad is slightly offbeat. Perhaps that is the reason large portions of the fort still survive today. As a person with an obsession for auto-rickshaw rides, the fort was a disappointment for me. The fort can act as a retreat, but it is not as easy to get off the space using the compact auto.

But all suffering can be forgotten when one sees the sturdy walls and shapely curves of the Tughluqabad fort.

Here the experience was markedly different from that of my other solo sojourns. The fort seemed deserted. The warm sun, despite winter, could have been a reason but not reason enough.

Ahead of the fort within its enclosure sat Ghiyasuddin Tughluq’s tomb, which was slightly elevated so that it could be viewed from this side of the fort. I could not hold my excitement when I saw the dome (or the Gumbad). The thought of Battuta’s spell rushed into my consciousness.

Having narrated Ghiyasuddin’s tomb, Battuta says:

He was carried by night to the mausoleum, which he had built for himself outside the town called Tughluqabad after him, and he was buried there.

… In it was the grand palace whose tiles he had gilded so that when the sun rose, they shone with a brilliant light and a blinding glow that made it impossible to keep one’s eyes fixed on it.

I sat there reading the words of Battuta off the pages of the book I carried with me.

That makes me acknowledge the man without whom this journey would have been impossible: Tim Mackintosh Smith. Tim Mackintosh Smith, like Dalrymple, was a lover of his subject. His love of Arabic has made him a citizen of Sana’a. And also, with his passion he knitted the fabric of Battuta’s experience into something tangible. What would otherwise have been a trip in Delhi’s busy and empty spaces was for this time, a journey through the cliffs and gorges of time.

All images are taken by the author, unless mentioned.

Revanth Ukkalam is a student of History at Ashoka University. This post was originally published on his blog here. When he is not reading books, about books, or talking about them, he finds himself engrossed in classic Telugu films.

Readers' Reviews (4 replies)