A love letter – ‘The Last Mughal’ by Dalrymple

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Read out this Theel for me”]

William Dalrymple’s most celebrated scholarly classic – The Last Mughal -The Fall of a Dynasty is widely regarded as his best. It covers Delhi and North India during the Revolt of 1857-1858 against the British empire. The revolt was ultimately a failure, but it did result in passing the control of India from the East India Company to the U.K. crown. However, it is interesting to note how the events of 1857-1858 radically altered Delhi forever, and the three-hundred-year-old Mughal dynasty met the most undignified collapse. The man who Dalrymple places at the epicenter of this calamity is the last Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar (1775-1862).

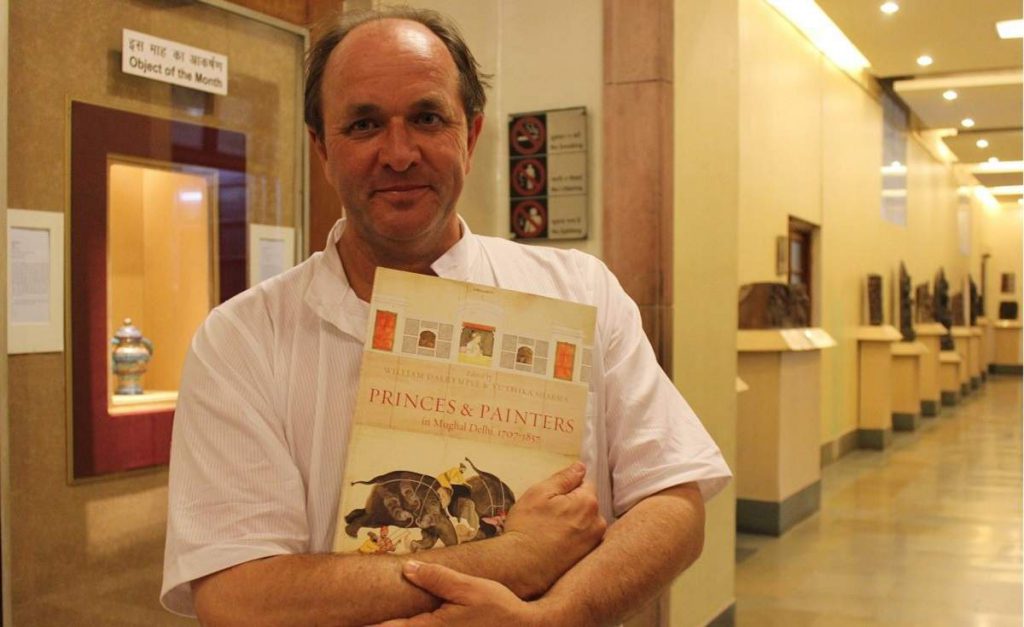

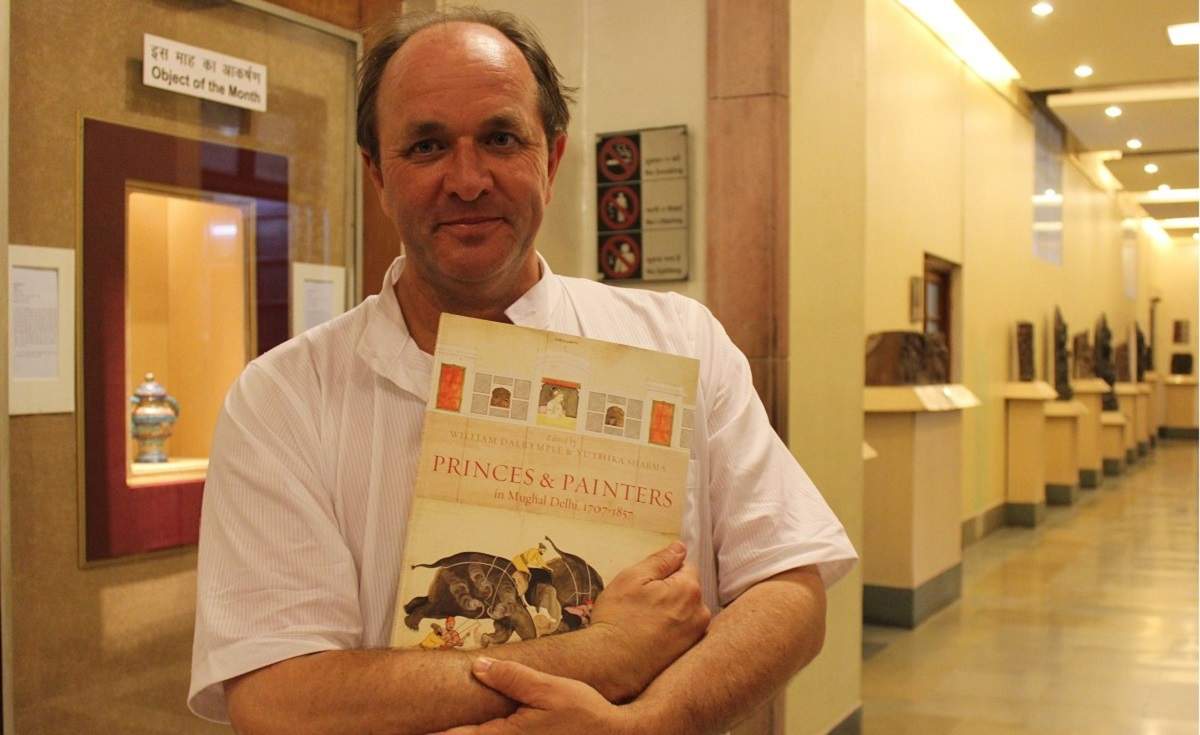

It took Dalrymple and his dedicated colleague Mahmood Farooqui four years to work on the Mutiny papers at the National Archives together with other sources. It marks the completion trilogy of his books on Delhi, the erstwhile capital of Mughals The first two- City of Djinns and White Mughals- explored his tryst with a city that was once inhabited by one of the most enchanting street cultures and described as the “most splendid palace in the world.” This city eventually turned into a metropolitan city with most of its heritage in ruins. It is essential to explore his context to understand this masterpiece, a pinnacle of his never-ending love affair with Mughal Delhi. Growing up in rural Scotland on the shores of Firth of Forth from his birth in 1966 till the first 18 years of his life, he was untouched by any whiff of oriental culture. He describes himself as the least traveled of all his school friends. His parents, convinced that they were living in the most beautiful place on earth, rarely took their children out for a holiday. So when Dalrymple landed at New Delhi airport on the foggy winter evening of 26 January 1984, Delhi was destined to create an impact on him that was more profound than on most teenagers. The sights of broken tombstones half hidden by bushes, the diwan-i-khas of the Red Fort looted of its previous glory, Mughal Delhi was like a lost gem. He found himself a job at Mother Teresa’s home beyond Old Delhi. This proximity further provided him with a chance to explore the ruins of Shahjahanabad. Afternoons would find him slipped in some shady corner reading a book. Sitting in the city, it was natural that he grew fascinated with the emperors that built it. He learned about the dynasty, and this admiration led to his decision to write a history of the city, especially of the court that presided over it. Much like in the ideology of the Mughals wherein the history of the city and the court is synonymous with that of the emperor, Dalrymple’s account is a narrative that disperses Zafar’s life with that of his city. Contrary to the assumption that The Last Mughal is a biography of Bahadur Shah Zafar, the last scion of the dynasty, it is a tale of a vibrant city’s death that Zafar literally and metaphorically personified.

Delhi is not a location in the story, but the protagonist. A city of Sufi poets, seductive courtesans, of Hindu and Islamic religious fabrics interspersed in a great cloth, of Turks, Mongols, and Armenians living together, of Hindustani, Urdu and Persian, of perfumes, gardens– a city of Emperor Zafar and yet not his anymore. British gained formidable political power post the Battle of Plassey (1757). Over the next century, by war or tactic, they had conquered most of the subcontinent. The Mughal emperors were essentially reduced to chessboard kings. Zafar acceded the throne in 1837 in his mid-sixties when the economic and political power of the Mughals was irretrievably lost. Yet, it remained a symbol of authority. Zafar also managed to preside over one of the greatest cultural renaissances in Indian history. Mughal Delhi, under Zafar, kept breathing a life of great cultural, but almost no political affluence. It was the failed rebellion against the British in 1857 that proved to be the final nail in the coffin of the Mughal Delhi both Zafar and Dalrymple loved so dearly.

Sufis, dervishes, and avdhoots mixed freely. Presents to Hindu shrines were often sent by the Mughal harem. The British cantonment to the north of the Red Fort was physically isolated, yet it remained in close communication with the political quarters of the Red Fort and a participant in the cultural hustle-bustle of the city till at least 1820s. The military sahibs went hawking, wrestling, and hunting with their native sepoys and servants. Fluent in Hindustani, they were familiar with the customs and manners of the country. A new race of white Mughals emerged in the first two decades of the nineteenth century resulting from matrimonial alliances of the whites with the natives. This changed when the officials developed a sense of racial superiority in the 1840s and explicitly discriminated against the Indians. Yet the formal and diplomatic ties with the royal family remained good. Due to the endearing respect, people of Delhi had for Zafar as a scion for a great imperial dynasty, the British favored the continuing rule of the king as a puppet ruler.

The native Christian population also lived a very traditional Indian way of life despite their recent conversion and mostly separated quarters. There was a sense of communalism that nevertheless did rise once in a while. The rebellion broke out in full swing in May 1857. Certain factions of the Muslim nobility did give a cry of Jihad against whoever opposed, in their opinion, the return of Mughal power, mainly certain powerful sections of upper-caste Hindus and military men. This was avoided by the timely intervention of Zafar himself, who was dead against this kind of religious fundamentalism. The rebellion did become a war against anyone seen as an ally of the British. So the homes of moneylenders and rich were looted, and Christians and British seen as opponents of traditionalism killed as well. Perhaps the rebellion was an attempt to create a more egalitarian society, a way to turn over the existing hierarchy with the British at the helm. By September, however, as British regained Delhi and mutineers were put to trial and executed, the opposite became evident. In two months, Zafar was sentenced to exile in Rangoon along with some family members. Without the emperor, the imperial hierarchy had no basis for survival. The court dissolved, with most of its members killed. The physical splendor of Red Fort was too denuded. The city was a virtual battlefield and by October a military cantonment. Most employees of the imperial culture migrated from the city, some perished, and all of them lost financial patronage. Most importantly, it was the larger culture of an imperial legacy that was almost overnight drawn to extinction. Women, as is mostly the case, suffered immensely. The old women were killed while young wives and princesses of the royal household turned into prostitutes. Jama Masjid was not returned to the city’s Muslims till into the next year, and when this was done, it was a space for namaz and little else.

With most of its population killed or in dungeons starving to death, hardly anyone was left to mourn the demise of the imperial legacy. Mirza Ghalib, the ustad of Zafar and his court poet, was few among his colleagues to survive and record the grief. His accounts have been extensively used by Dalrymple. The book is a must-read for a history and culture enthusiast. It’s an ode to a city that survives only in the tiniest material fragments today, but there was an era when it was a thriving economic, political, and cultural capital. The book reads like a passionate love letter to that Delhi and is bound to fill you with nostalgia. Not surprisingly, this letter is associated with the greatest lovers that Delhi had – its last emperor and its greatest historian.

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

I love my work.??

Great insights… well articulated. It made me want to read “The Last Mughal”. Great work Bhumija!

Thanks Rahul.I love when a sharp mind analysis my work ??????Yeah, book is a must read!

Compliment in reply of a compliment; noicce??

Well written! ??

Aww . Thanks love!???

Your literary prowess is unmatched, amazing piece!!

Hehe thanks a ton. I would love to know your name.

Wonderfully written Bhumija. I like your writing style. Keep it up!

Thanks a ton! Hmmm, May I know your name?

Quite Enlightning. Very well written!

Thanks Bhawna!

Very well written! Keep it up ?

It’s a very well written piece! Well researched and brilliantly articulated.

Thanks a ton Chitra! Love when writers support writers !???

Such a good and an engaging article by one of the most talented writers I know. Keep up the good work, Bhumija! 🙂

Thanks Arnav

Means a lot.