Why schools should encourage peer learning

Dr. Jyoti is a professor at Delhi University.

Avani Sharma

Avani Sharma is a BElEd IVth year student at the same department of elementary education, Gargi College (University of Delhi).

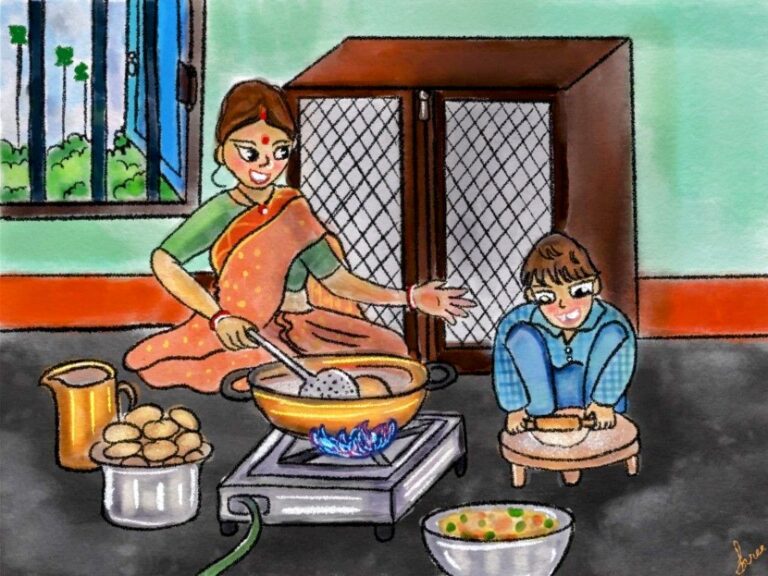

Consider this scenario. A middle-aged woman is diagnosed with the king of maladies, an aggressive variant of breast cancer, a word no one wants to hear. She needs a comprehensive, precise and personalized treatment plan tailored to her diagnosis. This plan needs exhaustive inputs across the fields of pathology, radiology, surgery, histopathology, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, precision oncology, interventional radiology, nuclear medicine, targeted therapy and symptom management. Each of these is a highly specialized knowledge domain of super-specialty doctors. The treating doctor needs to learn from each one of these experts in developing the treatment plan. This plan is so complex that neither of these specialists is capable of preparing it in his or her individual capacity. S/he brings all of these super-specialists together as peers; presents the diagnosis to them, collates inputs received, writes a treatment protocol and justifies it before his/er peers. This learning from peers provides him/er with a thorough plan to treat the woman patient. The words of American psychologist-educator Jerome S. Bruner (1915-2016) that learning in most settings is a communal activity, a sharing of culture’ (Bandura, 1986: 127) aptly captures how coming together of super-specialist doctor peers as a medical community can address some of the complex problems facing the world. In this case, this woman patient, the knowledge needed to benefit her becomes functional only when different domain-specific peers come together for a complex treatment. This kind of peer learning is the foundation of solving problems in most advanced fields of work. It involves the process of learning with and from each other. It is valuable in making knowledge functional especially in areas that require advanced knowledge systems.

Yet this key concept has not received the attention it merits in educational psychology, educational theory and school classrooms. Psychology as a discipline of study in its modern form that is practiced in contemporary academia emerged from philosophy. It began as a subject that studied the science of mental life and therefore explored questions such as: how does learning take place in individuals? How do different types of knowledge develop? Learning was considered to be an individual process in the early studies of the psychology of education. The first modern theory of learning was offered by American psychologist Edward L. Thorndike (1874-1949) in his influential book Animal Intelligence first published in 1911. Learning was66 explained as an association or a bond or a connection between environmental stimulus and an individual’s response to it. It was often referred to as stimulus-response (S-R) theory of learning. The unit of action for both stimulus and response was the individual. The student was the actor who generated S-R bonds or connections within herself or himself which constituted an individualistic account of learning. More than a century later, prevailing school practices continue to tend to be based on the presumption that classroom learning occurs because teachers plan instruction, provide appropriate reinforcement and this leads to development of knowledge among students. In other words, students learn because teachers teach them.

Learning in psychological studies in education was considered an individualistic process which teachers could drive by instruction (Skinner, 1968). Behavioral theories of learning developed on this assumption have dominated schooling practices in most societies’ world over. Instructional approaches such as Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives that view learning as a linear additive process of acquisition of skills like recall, comprehension, and analysis in observable terms are derivatives of behaviorism in education. So are testing regimes that certify learning in terms of written scripts of students.

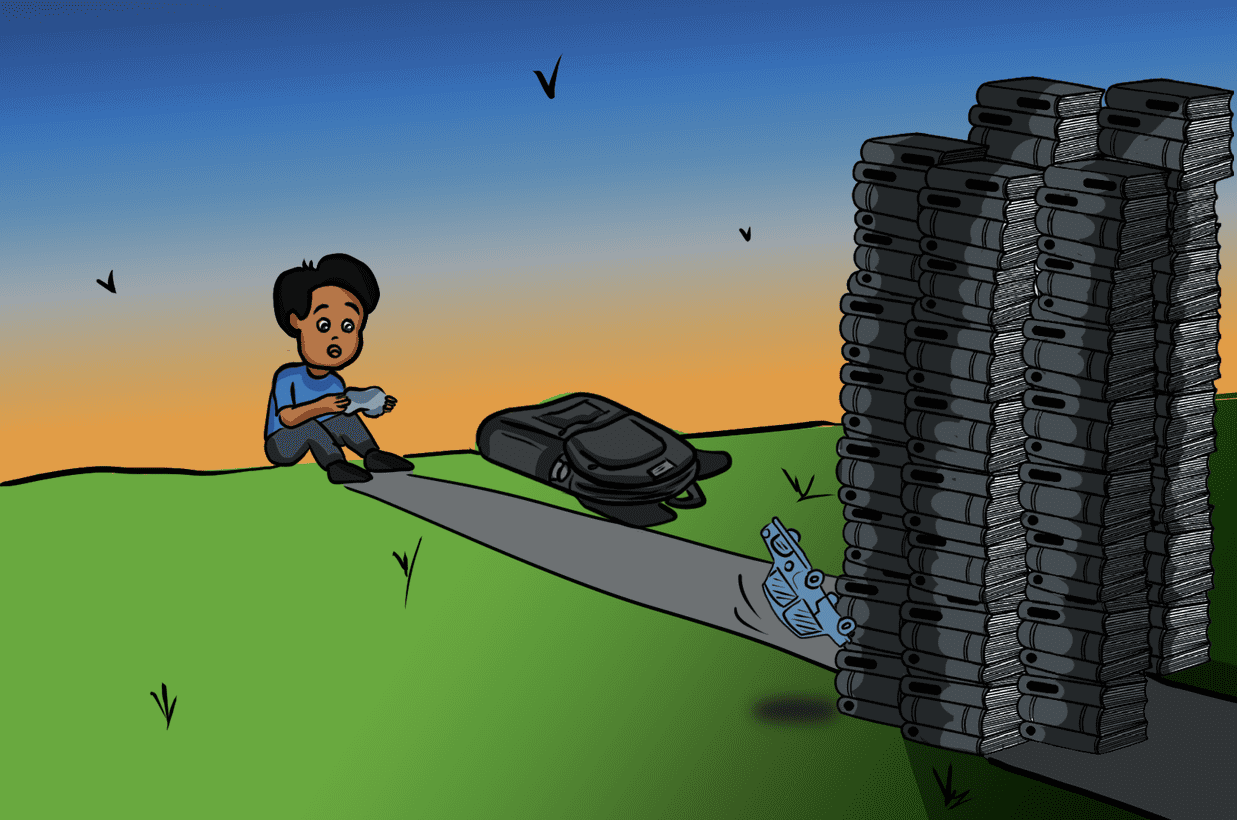

If learning can be accounted for in behavioral terms in which our school education systems are framed, then why do education surveys and reports such as those by civil society organizations like Pratham and even by government organizations like the National Achievement Survey of NCERT; indicate a learning crisis in primary and middle grades year after year? (ASER, various years). Two of the startling findings from the most recent ASER survey (2023) with reference to the current status of foundational skills for youth in the age group of 14-18 are as follows. First, around 25% of this age group still cannot read a Std II level text fluently in their regional language. Secondly, more than half of them struggle with division (3-digit by 1-digit) problems, a skill which is usually expected in Std III/IV. While the methodology of such large-scale surveys and the flawed emphasis on proxy indicators of learning has been critiqued by several educationists; the reports do alert us to some of the ills of our school systems. Perhaps there is a need to understand classroom learning in schools beyond instruction by teachers which may be among the reasons for this alleged learning crisis.

In contrast to the learning-as an individual, process approach, the implications of which are discussed above, Russian educator L.S. Vygotsky (1896-1934) proposed cultural historical theory suggesting a view of learning as a social process that took place as a result of social interaction. According to him, the interaction of students with more knowledgeable peers and adults was particularly important in this process. This social basis of learning seems like an evident truth but had not received the attention of any theorist for more than a century of the history of learning theory. No wonder, Bruner in his introduction to one of the translated works of Vygotsky’s Thought and Language wrote: ‘Vygotsky is an original’ (1962, p vi). Vygotsky explains learning as follows: there are functions in the student’s mind that are in an embryonic stage without having matured. They are in the process of maturation. He used the analogy of buds or flowers for the unmatured mental functions. These were reflected in the student’s independent problem-solving of tasks, problems, and questions. Then there was the higher level that can be seen when students are solving tasks in collaboration or association with a more able peer. The peer may be someone from the same class but one who has already learnt to solve the given task. The gap between the former and the latter he has termed as Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD).

Students learn to achieve higher levels of understanding with the support of peers who are more knowledgeable, leading to a process like the flowers turning into fruits. Peer learning has potential within a student’s ZPD, to bridge gaps in their knowledge and understanding. It occurs when teaching is planned for students so that they learn by coming together to understand ideas; by sharing what they know and supporting each other.

Vygotsky’s views on the social aspect of learning are often contrasted with those of Swiss educator Jean Piaget (1896-1980). Explaining this distinction Wood (1998) writes succinctly,

Children who are unable to perform tasks, solve problems, memorize things or recall experience is when they are left to their own devices often succeed when they are helped by an adult. Piaget…. takes a somewhat negative view of such apparent successes, claiming that they involve the teaching and learning of procedures and not the development of understanding. He views ‘genuine’ intellectual competences as a manifestation of a child’s largely unassisted activities.

However, Piaget also recognized peer interaction as an important source of children’s learning and mental development during some of the early stages of cognitive development. He recognized that children in preoperational stage of mental development (from ages two to seven approximately) are self-centered in their thinking as well as language (using the term egocentric for their thinking). Other children have mental structures similar to theirs and therefore interaction with peers can be beneficial in providing feedback upon their ways of thinking and perspectives (Piaget, 1951). Teaching that recognizes the value of learning from peers during social interactions is thus valuable. Such teaching also supports diversity as different students come together creating an inclusive environment in the classroom as opposing perspectives are confronted.

Psychologists, across theoretical positions, have further argued that solving problems with other children produces greater learning rather than solving the same problems alone (Seigler, 1998). Teachers thus need to design instructional approaches, plans, and strategies that encourage peer learning in the classroom. This involves exploring peer learning practices that are already existing among students in the classrooms, planning lessons to generate further possibilities for peer learning across all subjects and assessing the value of peer learning activities by observing the classroom. It can be concluded that children’s potential for learning is actualized in interactions with peers who potentially offer possibilities for development of knowledge in varied domains including school subjects.

References

- ASER Annual Status of Education Reports (various years). ASER Centre, New Delhi: Pratham.

- ASER (2023). ASER Centre, New Delhi:Pratham. available at https://asercentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ASER-2023_Main-findings-1.pdf

- Bruner, J.S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA Harvard University Press.

- Piaget, J. (1951). Play, dream and imitation in childhood. New York: Norton.

- Seigler, R. (1998). Children’s thinking, University of Michigan: Prentice Hall Inc

- Skinner, B. F. (1968). The technology of teaching. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts.

- Vygotsky, L.S. (1962). Thought and language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wood, D.( 1998) How children think and learn: The social context of cognitive development (2nd edition): Blackwell Publishing.

Yes, I completely agree with the article’s perspective. I’ve experienced this both as a student and as a teacher. As a student, I always learned better when I worked with my peers—it made the process more interactive and less stressful. Now, as a teacher, I’ve noticed that my students seem to thrive when they engage with each other rather than passively listening to me. I’ve also realized that I don’t enjoy teaching as much when it becomes a one-sided lecture. Involving students in discussions and collaborative activities makes the entire experience more meaningful and fulfilling—for them and for me.

As a student, I can say that learning with friends or classmates makes the entire process feel lighter and more meaningful. There’s something about sharing ideas and figuring things out together that brings a sense of connection and support. When a teacher is just explaining things, it often feels like a task to complete, and I end up feeling weighed down. But with my peers, there’s room to make mistakes, ask questions freely, and really explore ideas without pressure. It’s not just about understanding better—it’s about enjoying the process of learning and feeling that we’re in it together.

This article emphasizes the importance of students learning from each other. Peer interaction helps build community, improve teamwork, and develop social skills. The author offers practical tips for using peer learning in classrooms, making it a valuable read for educators seeking to create a more inclusive and engaging environment.

“This article highlights a crucial aspect of effective learning: peer-to-peer interaction. By encouraging students to learn from each other, schools can foster a sense of community, promote collaborative problem-solving, and help students develop essential social skills. The author’s suggestions for implementing peer learning in classrooms are practical and well-reasoned. A great read for educators looking to create a more inclusive and engaging learning environment!”

This article shows how teamwork and learning from each other are crucial in solving complex problems, like treating an aggressive cancer. It explains that no single expert can handle everything alone, but by working together and sharing their knowledge, specialists can create the best plan for the patient. As an educationist, I see this as a great example of how learning in groups helps people solve real-world challenges. Jerome Bruner’s idea that learning is a shared activity reminds us that education should encourage collaboration, critical thinking, and teamwork. This way, students and professionals can prepare to tackle complicated issues in any field.

This article provides a comprehensive and insightful exploration of the concept of peer learning, highlighting its significance in the educational landscape. Theoretical perspectives, real-world examples, and practical implications to make a compelling case for the importance of peer learning in schools are skillfully woven in this article. The article also highlights the limitations of traditional instructional approaches, which often prioritize individualized learning over collaborative and social learning experiences. By contrast, peer learning is shown to promote deeper understanding, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills, as well as foster a sense of community and inclusivity in the classroom. This article is a valuable contribution to the ongoing conversation about the future of education. It challenges readers to rethink traditional approaches to teaching and learning and to consider the transformative potential of peer learning in enhancing student outcomes and promoting more collaborative and inclusive learning environments.

This article brilliantly highlights the value of peer learning, which I’ve actively incorporated during my teaching internship. In almost every subject, I planned group tasks—like solving math problems together or reviewing each other’s writing in language classes. I stayed close by to guide them if needed and noticed how much they learned from explaining ideas to each other. It also helped students who might usually hesitate to participate in class often shine in smaller peer groups, building confidence along with their knowledge. They feel more confident and involved. Peer learning has such potential to make classrooms more inclusive and engaging. Thank you for sharing these insightful ideas!