The Phenomenon called MGNREGA – Part 1

Shanmukha was a managing editor at the journal

In April 2004, the Congress had come into power after a bitterly fought election. They immediately got down to appointing a Standing Committee, in the second half of 2004, to begin work on the National Rural Employment Guarantee Bill, that was to be tabled the next year in Parliament. This was a promise that was at the core of their election strategy and manifesto. As the Parliament’s monsoon session of 2005 was fast approaching, the corridors of the Rural Development ministry was abuzz with activity. Almost 15 years back, during this month, secretaries, economists, policymakers, Congress party leaders, including Sonia Gandhi herself, were preparing the document to be tabled in the Parliament to guarantee employment to millions of rural Indians– the ‘Right to work,’ under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA).

MGNREGA has been hailed by many as the largest rural employment schemes in the world and has been credited with initiating a splendid transformation in India’s rural areas in many respects. Over the years, it has seen many changes and iterations, has had its fair share of controversies, and has also built up a sizable opposition that questions its necessity and efficiency. It has featured prominently in all of the Lok Sabha election campaigns since its inception.

The Making of the Market Economy

John Maynard Keynes, in his groundbreaking work The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money argues that the way to boost a country’s economy consists of increased government expenditure, which puts disposable money in the hands of the public, initiating a demand for goods that would lead the production to restart. This was contrary to the prevailing theories of supporting the producers and manufacturers to stir consumption in the economy. Similarly, could the answer to poverty alleviation lie in solving these demand-side faults and cracks? Governments across the world indulge in various types of supply-side policies to solve problems of poverty. The public distribution system in India is one such example. The supply of grains, cereals, petrol, etc. are all massively subsidized to ensure that even the poorest are able to feed themselves sufficiently. The other actions that governments use are hiking import tariffs, slashing taxes for corporates, provision of land at dirt cheap rates to set up manufacturing plants, etc. However, across the world, it has been noted that such supply-side interventions are not particularly efficient, have furthered income inequality, and would serve better if they are used as supplements to demand-side interventions.

Keynesian economics, being a strong supporter of demand-side interventions, suggested putting money in the hands of people and creating jobs to pull an economy out of depression and pull people out of poverty, thus stimulating them to consume and demand products. In his book, he says, “if the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coalmines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave it to private enterprise on well-tried principles of laissez-faire to dig the notes up again in the note-bearing territory, there need be no more unemployment.” The real income of the community, and its capital wealth, also, would probably become a good deal greater than it actually is. It would, indeed, be more sensible to build houses and the like; even if there are political and practical difficulties in the way of this, the above would be better than nothing. Simply put, he suggested the government to pay people to dig up holes and cover them back. He argues that what job has been done is irrelevant as long as a job has been created. Let us now hold this thought for a while, as we go on to see the origins of the employment guarantee schemes in India.

Birth of MGNREGA

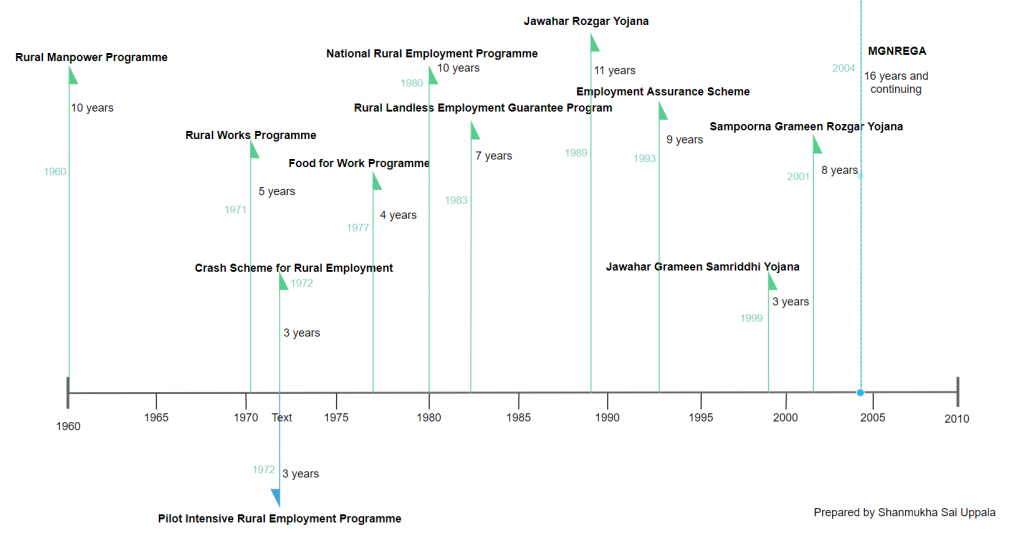

There have been many demand-side interventions in India, but each had their objectives and were plagued with implementation and monitoring problems. A few states came up with their specific employment schemes. The situation was a little too disorganized, until the entry of the Food for Work Programme (FWP) in 1970, renamed as National Rural Employment Programme (NREP) in October 1980, and further rechristened as the National Food for Work Programme in 2004.; this served as the programme design for the MGNREGA, which came up in September 2005. The FWP gave away 2.5 kgs of wheat per head per day of work spent, along with wages. In a report bought out by Comptroller and Auditor General of India (CAG), the body that audits or verifies the expenditure claims of the government, severe glaring loopholes were exposed, which showed massive pilferage and the number of contractors benefited financially using political clout. To ensure greater control, this scheme (NREP), was merged with Jawahar Rojgar Yojana in 1989. Running for almost two decades, Jawahar Rojgar Yojana, was the longest and most successful scheme, with various nominal and structural changes (Jawahar Gram Samriddhi Yojana in 1999; Sampoorna Grameen Yojana in 2001), until it was merged with MGNREGA in 2008.

The politics of MGNREGA

The BJP has always felt that supply-side interventions would be the cure to all that ails the Indian economy. No wonder, they were adamant and vociferously opposed the MGNREGA, when it was tabled in the Parliament. While they cited many reasons, the main argument they put forward was that given the history of the employment schemes (that were all demand-sided) and policies implemented in the past, it was foolish to convert such a welfare scheme into an Act. With the BJP in power and Congress in opposition in India from 1999 to 2004, the Congress was desperate to win the next elections. They needed something to mobilize the voters. While there were already plenty of schemes that were created towards rural employment, there was a need for something drastic, as there was no tangible result from these existing schemes. The only problem, however, was that a rural employment guarantee Act would be a massive burden on the government since it would have to be centrally financed in majority. When Congress lost Rajasthan, a stronghold, in 2003 elections, it weakened resistance to include a brief of the Employment Guarantee Act (EGA) in their manifesto for the 2004 elections.

With Congress emerging triumphant in the 2004 elections, it immediately got to work setting up various committees and sending out directives to various ministries to begin the work of an EGA. Once tabled in Parliament, it was unopposed as an idea but met with much resistance as the details were looked into. Commenting on the first draft of the EGA, Jean Dreze, a celebrated economist and member of the drafting committee, said, “The draft MGNREGA entered national policy debates in India… like a wet dog at a glamorous party”. After much to and fro, the Act was passed unanimously, yet it was a compromise. The problems of implementation began in early 2006.

The end of Congress

It was a Congress pet-scheme, and they were never coy to sing its praises. The numbers were impressive too, even if they were to be taken with a pinch of salt. With Congress completing a decade in power and being ousted in 2014, it was up to the BJP to keep it or leave it. However, the BJP has not been impressed by it. Narendra Modi has openly expressed his distaste with the MGNREGA and said that it was a ‘living monument of the failures of the UPA government.’ Yet, the BJP has given it the highest ever budgetary allocation, after it was ignored for two consecutive years. What happened?

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

Readers' Reviews (1 reply)