The Nehruvian social dilemma

Debayan Ghatak is a student of Political Science. He is an avid reader who loves to keep himself updated regarding various global happenings besides taking a keen interest in Indian politics along with International Relations.

Among all the Third World countries which managed to obtain their independence roughly around the latter half of the twentieth century India’s case is a novel one considering its diverse body politic amid its strong democratic base.

At the time of independence, the Indian society which was just recovering from the wounds inflicted by the tragic Partition was still divided based on caste, linguistic and religion induced differences even consisting of some erstwhile princely chiefdoms signifying separate conclaves of power. It also belied the hopes of Marxist theoreticians lacking a differentiated bourgeoisie and proletariat.

While the peasantry which constituted the bulk of the Indian populace during the said period were themselves divided along with spatial, economic and cultural considerations, the workers based within the still-nascent Indian industrial sector could not come together as a coherent mass. This is because of a looping network of trade union bodies engaged in the mutual competition which ultimately broke up into several conglomerates of co-operative limited experiencing varying degrees of governmental regulation.

There were also deep-seated contradictions within the so-called Indian elites coming up from a rich agrarian background of colonial favouritism and large scale profit ventures accruing from the Permanent Settlement.

While some of these erstwhile landowning classes were attracted towards the British commercial establishment surrounding the port cities and engaged themselves in various business and trading activities, others assuming the position of absentee landlords became the new rentiers. This rupture in the common parlance of the Political Sociology of the 1960s came to be signified as the famous Urban-Rural Divide.

Some Marxist theoreticians of Indian politics like Pranab Bardhan believe that besides these two broad elite social segments there was the middle-class intelligentsia in the body of bureaucrats, professors, engineers, doctors and others belonging to the developing service sector of the economy. They came to assume high positions within the emergent state apparatus essentially coming from a rural background bearing the epithet of the first generation migrants.

These stratum of people had an important position to play in consolidating the state’s preponderant presence over the socio-politico-economic life as they effectively played one class against the other by taking help from the erstwhile planning apparatus.

This pertained, on one hand, to the state’s apt handling of the rural elites by making sure that there was no power assertion on their part through a process of gradual state intervention in the form of land reforms within the hitherto unorganized sector of the economy.

On the other hand, the state only warranted for a minor position to be played by the industrial elites by providing for maximum state investment within the key sectors of the economy and vesting the latter’s consummate management in the hands of the state’s managerial elites. Only a piecemeal arrangement was provided for the private sector under the aegis of the infamous License Permit Raj.

Though some of the private players who were themselves a part of the ruling dispensation took advantage of this position in consolidating their base because of the dearth of foreign competition under a protectionist regime.

From the very First Five Year Plan onwards, a clear wedge was observable among the agrarian and industrial interests which were highlighted in the differential allocation of sparse state resources. This ensured the continuance of the state’s commanding position as a third actor within the economy which in turn helped the new political class to reproduce its power.

According to Bardhan, the Indian society was essentially a medley comprising of divergent class blocs engaged in a spirit of confrontation with each other highlighting the divisive bourgeoisie in the form of a coalition of class. In the words of the Marxist scholar, this was a clear case of the Asiatic mode of production where the class contradictions were not that much matured that it would lead to a revolution.

It is now that we may attempt to understand the way in which these manifest class contradictions played out in the Nehruvian period of the Indian polity under the aegis of a ‘Strong State’ compounded with an additional emphasis on a modified form of Socialism so to say in order to suit the Indian context.

The Nehruvian state undertook its massive journey towards catapulting India onto the path of development to match the same level of industrial and agrarian self-reliance as observable among the countries of the developed world. There were high hopes and aspirations heaped upon the new-born state commensurate with an ordinary Indian’s belief that the independent polity embodied freedom from the manifest socio-economic disabilities coming down since before the advent of colonial antiquity.

The state also enjoyed a certain amount of legitimacy as the reins of power was in the hands of the Congress considered by many to be the harbingers of Indian independence. A trust factor premised upon a rational and procedural model of governance could be discernible in the state’s institutions in line with the ethos then prevalent in the erstwhile post-colonial world to curb red-tapism in the form of an anti-corruption drive.

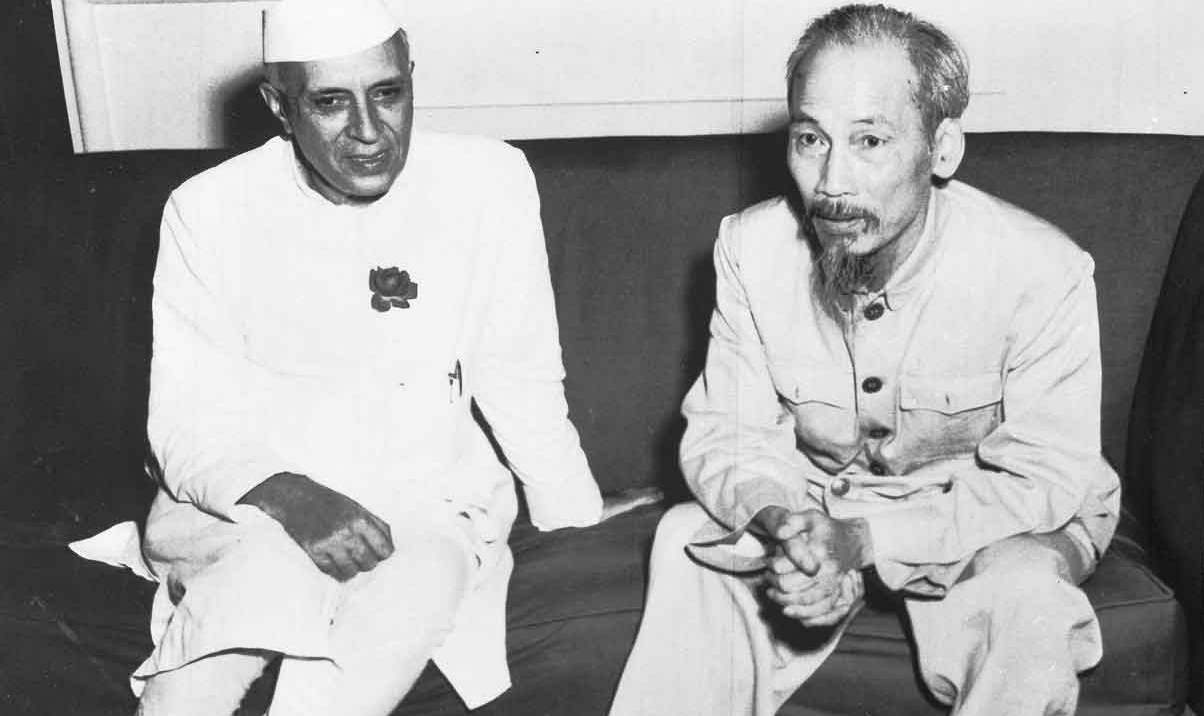

Legitimacy also accrued through other non-performative means in the persona of Shri Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India. He was the living embodiment of Socialism so to say signifying how a degrading colonial rule left India with a stagnant economy entailing the need to follow a focussed path of development.

He aptly held up the much avowed Nehruvian consensus in the form of Socialism, Secularism, Democracy and Mixed Economy. Being a cosmopolitan statesman with an inherent ability to tackle international pressures, he possessed a charisma intertwined with the needs of the time to address an amorphous populace.

To address the manifold contradictions enveloping Indian society at the time of independence, the need of the hour was for a ‘third way’ of maintaining a fair amount of balance between public and private capital with an additional emphasis on state enterprises. Some of the pressures on the emergent polity included the problem of a haphazard production-distribution regime along with the looming crisis of food scarcity because of which the Indian state had to opt for imports belying substantial independence. The resultant product was massive malnutrition, inequality and poverty.

The main reason accruing for this moribund condition was the colonial state’s apathy towards upgrading the agricultural apparatus. The erstwhile land revenue system along with its emphasis on commercial crop cultivation left the domestic food production equation essentially unsolved.

India was indeed in a paradoxical situation. It needed radical social transformation but had also to face an entrenched status of power in the body of former Zamindars who resisted change of the existent settled framework.

One of the ways that were open for revamping our entire socio-economic structure was to kick start the process of planning to figure out sectors demanding immediate investment because of the state’s limited capabilities. The prevailing opinion was not to rely upon private capitalists as they would only think about their respective profit margin sidelining the question of inequality.

It was essentially a Dirigiste Model of Economy with the state virtually controlling the entire productive apparatus with no scope as such for private players to overthrow and manage the existent caste, religion and gender induced disparities.

This enduring need was fulfilled with the creation of the Planning Commission as a statutory body in 1951. The Prime Minister himself was its ex-officio Chairman guided by the presence of reputed Deputy Planning Commissioners. The First Five Year Plan laid emphasis upon the agrarian sector involving a large chunk of the populace in the form of primary activities. This was the arena where the Gandhian and Nehruvian ideas pertaining to the ideal village organization came to be extensively debated.

Some of the key ideas which influenced the operation of this erstwhile planning apparatus essentially sidelining the Gandhian model of decentralization was the insistence given to Fabian Socialism. This was a resultant of the various nationalist leaders’ academic venture to the London School of Economics in England at the end of the First World War where a lot of these developmental debates were crystallized.

This theory highlighted the role of the state to a big extent to remedy the glaring inequalities. Another reason fomenting the insistence on this ideology may be the fear of Fascism that was lurking within the minds of the Indian leaders at the time of independence essentially deploying Socialism as a countermeasure.

Alongside these considerations, the Keynesian model of the economy as formulated by J. M. Keynes in the 1940s warranted for massive state intervention at critical junctures of the economy to correct it that would increase the national demand by focussing upon employment generation. This idea resonated the concept of a ‘welfare state’ premised upon egalitarian principles of equitable economic distribution.

But during Nehru’s time, the term ‘Socialism’ was never inserted within the actual Constitution itself as was done during the tenure of Indira Gandhi to give vent to her populist appeals. The Nehruvian state began to face criticism because of its covert policy of accommodative politics aimed towards the industrial and agrarian lobby. The latter especially staunchly resisted the plan to introduce sweeping land reforms entailing the redistribution of the existent land holdings.

Thus the Land Ceiling Act which wanted to demarcate a particular amount of land as the optimum holding limit and the Tenancy Act which provided certain legal entitlements to the hitherto disprivileged tenants working on the land for a specific lease period failed to see the light of the day. Both these laws were passed in the Parliament and it was up to the individual states to implement the same.

In most of the states, it failed to be put into effect owing to the staunch opposition of the landholding elites. In some of the states where these progressive laws were indeed implemented were West Bengal and Kerala as constituted in the body of sharecroppers. This is also because there was a persistent presence of a strong Left Movement coupled with a historical background of tribal and peasant insurrections.

According to some scholars, the erstwhile ‘Congress System’ itself was a burning impediment towards social transformation highlighting the politics of accommodation by deploying local elite groups to head the Pradesh Congress Committees.

The former Zamindars who were the effective distributor of resources among the local populace played the role of patrons treating the marginalized and distressed classes as their clients. The resultant was an informal organization of local faction chains that was not warranted by the Indian Constitution’s emphasis on the Right to Equal Citizenship.

Though some of the landowners were indeed influenced by Gandhian Trusteeship principles along with the concept of Sarvodaya as propagated by Vinobha Bhabe, others did not care to follow suit.

The Panchayat System was itself not formalized and regularized and came to be dominated by the local notables. On the other hand, the targets of these proposed land reform initiatives, the peasantry itself was devoid of any class based solidarity also lacking a pan-Indian consensus. The latter’s insistence on caste based ascriptive identity was compounded by the communalisation of Indian politics going on since Partition.

Because of these structural limitations there was the absence of any truly revolutionary class within the erstwhile Indian polity that was capable of bringing about a radical social transformation. The process of reforms that was pursued was mainly evolutionary and democratic in nature making use of the existent legislative apparatus.

Democracy itself became an instrument of accommodation for the Indian leaders which was not solely based upon equality or the ultimate good but sometimes aptly used to conceal inequality too. Some scholars like Sudipta Kaviraj questions whether democracy itself was a good idea having its own origin in a bourgeoisie revolution.

Francine Frankel, however, believes that democracy was deliberately chosen to mitigate inequalities and to ensure the participation of the people within the body politic. It was by making effective use of these aforementioned manifest means that the Indian state was trying to substitute a frontal attack upon the capitalist class itself on whose continued support rested the very existence of Congress.

Some scholars began to question whether the idea of development itself was inherently good to be pursued in the form of a policy. Looking at the intellectual history of the idea of development as propagated in the twentieth century, it is important to note that what is it that makes it so legitimate?

The idea of development that was essentially borrowed from the West, treated economic progress as a march forward from a backward to a progressive situation. For the Nehruvian state of 1951, the backward constituents included entrenched caste identities, an old kind of peasant culture not treating land as a resource but substituting it with a paternal and emotional bond having over-reliance on labour-intensive technologies. The progressive constituents on their part consisted of industrialization, the establishment of thermal power plants, setting up polytechnic institutes and IITs and investing in infrastructural development including the construction of iron and steel plants.

But amid this IMF and World Bank induced developmental agenda of 1944 which involved America disbursing foreign aid with strings, one particular model was left out that is the Gandhian alternative. We pursued a more catching up model of economic development by anointing a symbolic yet unimportant presence to the Gandhian dictums of self-help, self-sufficiency at the village level accompanied with the parallel establishment of cottage industries, animal husbandry and Village Swaraj.

The Nehruvian polity aptly bearing the epithet of a ‘big state’ made its presence felt in every aspect of an individual’s life including his/her moral sensibilities with its nationalist bias. The high state functionaries considered people mostly as illiterate beings unable to make true sense out of the state-professed idea of development. Side-lining the demands of a Gandhian epistemological community only one valid form of knowledge which was mainly top-down and based upon abstraction was put forward at the expense of a more locally oriented and bottom-up approach.

This developmental paradigm which was premised on capitalistic anthropocentrism compelled Nehru to treat dams as the temples of modern India without considering the villagers who were internally displaced at its expense.

The Nehruvian state despite its ups and downs was in the words of Rudolph’s characterized nevertheless by a strong level of Stateness notwithstanding its gradually crumbling edifice built upon the Congress System. It was compounded with the constant perusal of a flawed notion of development. But what followed this initial phase of the Indian polity was marked by a whole episode of rampant deinstitutionalization, ultimately culminating in the tragedy of the Emergency years.

References

1. Rudolph, Lloyd I. and Rudolph, Susanne Hoeber (1987). In Pursuit of Lakshmi: The Political Economy of the Indian State. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

2. Frankel, Francine R. (2005). India’s Political Economy, 1947-2004: The Gradual Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press.

Image Credit: Wiki Commons