The misinformed Mahatma

Today is the 151st birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, who is honoured with the title of ‘Father of the Nation” and credited with the achievement of independence of India from British imperialism. Both admirers and critics of Gandhi find this occasion opportune to shed light upon his philosophy of pacifism and non-violence and the consequences they bore on the polity of India from their respective standpoints. Thus, I, too, wish to cease this occasion to present a particularly important aspect of Gandhi’s understanding of the political doctrines of Islam or, more appropriately, Muhammadanism.

‘We become the books we read,’ said Matthew Kelly, so must have Gandhi for he was a serious reader. The fact that he read extensively about varied subjects ranging from religion, health & diet and politics to mathematics and poetry is evident from the donation of 4500 books that he made to the municipal library of Ahmedabad in 1933 when Sabarmati Ashram was confiscated by the British Government.

A man of Gandhi’s stature donating 4500 books is sure to catch the eye of anybody who is a reader himself. I found it rather interesting to investigate into the details of all the books that Gandhi read and donated to the library. To my good luck, an exhaustive list of such books is available today thanks to the hard work of Kirit K. Bhavsar, Mark Lindley, and Purnima Upadhyay. The Bibliography of Books Read by Mahatma Gandhi prepared by Gujarat Vidyapith enlists all the books that find a reference in Gandhi’s own works and the books from which Gandhi has cited something. Having come across such a list of books, I found it necessary to know which books Gandhi read about Muhammadanism, for he is charged with favouritism and appeasement of Muslims.

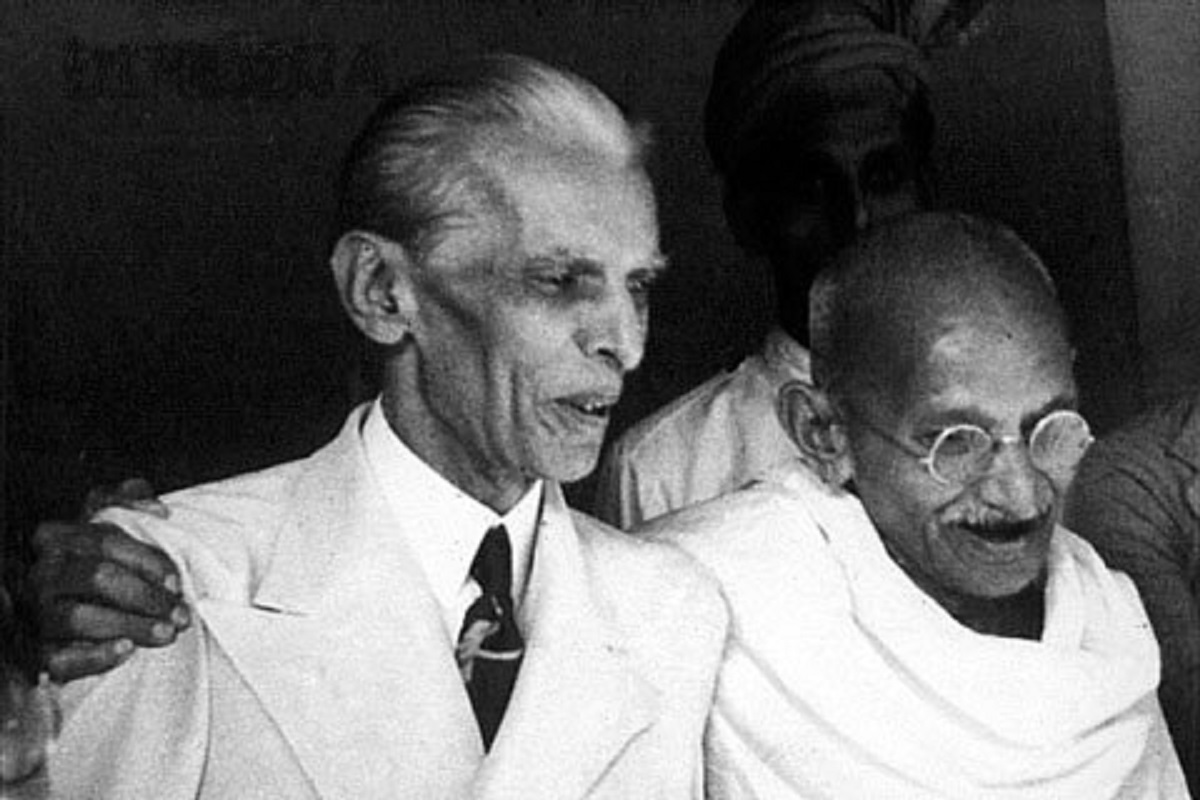

It is no secret that Gandhi aspired to be the leader of the whole of India, including Muslims, for which he strived very hard till the very last. Gandhi employed Congress in the Khilafat movement in the hope of gaining support from Muslims for the cause of Indian independence. However, the Khilafat movement was a pan-Islamic cause seeking to unite Indian Muslims with foreign Muslims against all infidels, which was contrary to the Indian freedom movement that sought to unite Indian Muslims with Indian Hindus against British imperialism. Moreover, the decision was flawed in principle itself, let alone the practice. The idea of supporting Turkish imperialism over Arabs and other non-Turk nationalities is absurd for the people who sought freedom from imperialism for themselves. Bothering Indian Muslims with a foreign cause as opposed to a more important and sensible domestic cause was a blunder in all respects.

Not only did Gandhi invest the resources of Congress in a non-negotiated pan-Islamic futile cause of Khilafat but also supported the Ali brothers’ invitation to Amir of Afghanistan for invading India after the Khilafat movement had failed to achieve anything apart from massacre, rapes, and forced conversion of Hindus at the hands of Moplahs. Gandhi supported the Ali brothers in the following words:

“I cannot understand why the Ali Brothers are going to be arrested as the rumours go, and I am to remain free. They have done nothing that I would not do. If they had sent a message to the Amir, I also would send one to inform the Amir that if he came, no Indian so long as I can help it, would help the Government to drive him back.”[i]

The failure to understand the true motive of Khilafat and invitation to invade could not be placed elsewhere but ignorance of the fundamental doctrines of Muhammadanism.

After the blunder of Khilafat came the ultimate appeasement offer to transfer the power entirely to the Muslim League. Much revered Maulana Azad made this proposal, and Gandhi approved it on August 6, 1942.[ii]

The final blow came in the form of Partition, which Gandhi vowed to resist at any cost, even at the cost of his life. But the fact remains that Gandhi, far from resisting it, ceded to the unreasonable demand of the Muslim League for the Partition of India on communal grounds. The Cabinet Mission Plan was passed by the All India Congress Committee (‘AICC’) at its meeting on June 15, 1947, by 157 votes to twenty-nine. Gandhi attended this session and spoke in favour of the resolution for acceptance. Durga Das notes that he put the issue in a nutshell, saying, “The fact is, there are three parties to the settlement-the British, the Congress and the Muslim League. The Congress leaders have signed on your behalf. You can disown them, but you should do so only if you can start a big revolution. I do not think you can do it.” Only Purushottamdas Tandon, out of the Congress’ topmost leadership, resisted this proposal of partition, saying, “Let us fight both the British and the League.” However, the leadership had already accepted the plan for partition, and Gandhi was employed to use his personal authority to get them a vote of confidence at the meeting.[iii]

In view of all the above-mentioned decisions, it is clear that Gandhi had resorted to appease Muslims in the hope of gaining their support for the freedom movement that he was heading. Despite numerous failures, he chose not to face the political realities of the time. He seems not to have even the vaguest idea of the political doctrine of Islam even after fuelling a movement for the restoration of the Caliphate, i.e., the universal political order of Islam. A caliph is not just a religious leader of the Ummah, as understood by Gandhi, but also the political leader of all Muslims across the globe. But Gandhi did not understand this fact as; clearly, he instead saw non-violence in Shrimad Bhagwad Gita and coined a rather farcical term of “Sarva Dharma Samabhava.”

The allegations on Gandhi of being less even-handed while dealing with Muslims was supported by many. Dr. Ambedkar criticized Gandhi particularly for his failure to condemn the murder of Swami Shraddhanand and other leaders of the Arya Samaj by Muslims, as opposed to his immediate condemnation of even the slightest act of violence from Hindus. It is not as if he never criticized Muslims; he indeed condemned Khwaja Hasan Nizami for his pamphlet Dai-i-Islam which called for the conversion of Hindus to Islam, by all means, fair and foul.[iv] One of Ambedkar’s many criticisms of Gandhi was this: “He has never called the Muslims to account even when they have been guilty of gross crimes against Hindus.” He cites a reference to several such crimes, including the murders of Mahashaya Rajpal and Nathuramal Sharma. Dr. Ambedkar pointed out that while the murderers were tried by the British judges, the Muslim leadership lent full support to them: “The leading Muslims, however, never condemned these criminals. On the contrary, they were hailed as religious martyrs (..) Mr. Barkar Ali, a barrister of Lahore, who argued the appeal of Abdul Qayum (…), went to the length of saying that Qayum was not guilty of the murder of Nathuramal because his act was justifiable by the law of the Koran. This attitude of Muslims is quite understandable. What is not understandable is the attitude of Mr. Gandhi.”[v]

On the other hand, Gandhi always turned the burden on Hindus to sacrifice for the sake of Hindu-Muslim unity. He never used his ‘most potent weapon’ against the fanatical Muslims but never failed to use it on Hindus, who loved and revered him.[vi] Mahatma knew fairly well that his fasting would not be able to move Muslims even a bit; therefore, he chose to transfer all the burden on his own kin who valued him deeply. Although all of it was done in good faith, at the end of the day, it showed how misplaced his understanding was.

There are only two ways that a person could possibly understand any given subject. We could either understand through our immediate perception that amounts to experience in the long run or through literature that we read about a particular subject. The former was always overlooked and rejected by Gandhi, no matter how clear the message be. He deliberately chose to overlook the threats that Muslim politics posed right from the Khilafat days. In that case, he was left with only the latter, i.e., reading the literature on Islam for the true understanding of its value system and doctrines. However, to my surprise, no book, which is an authoritative text for the knowledge of Islam, could be found among the list of books that Mahatma apparently read during his lifetime. Although he read the Quran several times but always in translation, that is why he consciously refrained from citing word-to-word from it. In such a case, he relied extensively on what his Muslim friends told him without even verifying if it was true. In one such instance, he said that “I am glad that Dr. Mohammed Ali assures me that ‘The Koran enjoins no such punishment as stoning.’”[vii] Whereas, in fact, the verses related to stoning were actually revealed to Muhammad as is reported in the Hadith narrated by Aishah as under –

“The Verse of stoning and of breastfeeding an adult ten times was revealed, and the paper was with me under my pillow. When the Messenger of Allah died, we were preoccupied with his death, and a tame sheep came in and ate it.” (English reference: Vol. 3, Book 9, Hadith 1944. Arabic reference: Book 9, Hadith 2020)

On a careful perusal of the list of books read by Gandhi, it is found that he read quite a lot of books on the life of Muhammad – the alleged Prophet of Islam. In a letter to Mirabehn dated November 3, 1932, Gandhi says – “There are many books on the life of the Prophet. The first place must be given to Amir Ali’s Spirit of Islam.” However convinced Gandhi might have been with the excellence of Amir Ali’s book, the truth is that it is not an authoritative work on the life of Muhammad. Probably the best book that Gandhi read on the life of Muhammad was Sirat-un-Nabi by Shibli Nomani, which is still referred by some scholars of Islam. But on the scale of authenticity and authority, the work of Ibn Ishaq on the life of Muhammad ranks first. Similarly, the work of At-Tabari on the history of Islam is considered the most authentic and authoritative work on the subject. Even scholars like Dr. Bill Warner suggest that one ought to refer to the original source texts in order to have a complete and clear understanding of Islam. And the original sources, in this case, are the works of Ibn Ishaq and At-Tabari that predate all other works on the subject.

Clearly, Gandhi never read these original source texts and, thus, missed the opportunity of learning from the literature on the subject. The mistakes that the Mahatma made could very well be accounted to his habit of overlooking and rejecting the most obvious threats that the political Islam posed before the Indian polity, but I would rather pin it to his ignorance of the very doctrines of Islam. He could not understand because he simply did not read. Even his perpetual rejection to acknowledge his failure in dealing with political Islam could be traced to his ignorance of the very nature of Islam that drove this politics. It bore disasters not only on the polity of India but also on the personality of Gandhi when he embraced the murderer of the man who decorated him with the title of Mahatma – Swami Shraddhanand. The least the ‘Mahatma’ could have done is to renounce the title bestowed on him before embracing the murderer of the compatriot to whom he sent his two sons to be looked after and educated at the Gurukul Kangri.[viii]

Therefore, the Mahatma that we have known to be the Father of the Nation was not an absolute Mahatma, but a ‘Misinformed Mahatma.’

References

- Elst, Dr. Koenraad. (2018). Why I Killed the Mahtma – Uncovering Godse’s Defence. New Delhi.: Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. (pp. 80)

- Majumdar, R.C. Struggle for Freedom. (pp. 695-696)

- https://sites.google.com/site/cabinetmissionplan/durga-das-5

- Jordens, J.T.F. Swami Shraddhananda. (pp. 148)

- Elst, Dr. Koenraad. (2018). Why I Killed the Mahtma – Uncovering Godse’s Defence. New Delhi.: Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. (pp. 84-85)

- Elst, Dr. Koenraad. (2018). Why I Killed the Mahtma – Uncovering Godse’s Defence. New Delhi.: Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. (pp. 105)

- https://sunnah.com/urn/1262630[viii] Elst, Dr. Koenraad. (2018). Why I Killed the Mahtma – Uncovering Godse’s Defence. New Delhi.: Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd. (pp. 105)

Featured Image Credits: Deccan Herald

Readers' Reviews (1 reply)