India’s COVID communication of stigma and blame

Zenia Taluja is working as a Research Manager at a multidisciplinary research organization offering data-driven insights for social development organizations. She completed her Master in Anthropology of Development and Social transformation from the University of Sussex.

Anmol Mongia is a research scholar who has recently completed her MPhil in Sociology from the Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University. Her interests include the study of religion and ethics, the philosophy of sports, and childhood studies.

Even though COVID-19 is a novel virus, the experience of a viral pandemic is not. Despite a long list of pandemic responses to refer to and learn from, we seem to be repeating the same mistakes, especially within the realm of risk communication. In the Indian context, divisive media communication is giving rise to old patterns of blame and stigmatization of a particular community, which is leading to impaired crisis response.

A Deja Vu: The pandemic of blame

The analyses of previous crises like Ebola, HIV/AIDS, SARS, and other such infectious diseases revealed that prevention of disease and communication in that regard is more effective when the public holds trust in the State’s efforts, which encompass medical facilities, risk communication, advice, and treatment. However, the history of pandemics and communication during such crises share an interest in attributing blame, rather than building trust. In the quest to reason and rationalize the outbreak of infectious disease, the question of ‘where did it start and how did it spread’ creates a boundary between “us” and “them”.

This is most often concretized by the blame game, a trope of which is stigmatizing those whose ‘otherness’ is historically located within the society. This pattern of accusation goes back to the 1300s when people linked the bubonic plague to the Jewish community. It can also be traced in the outbreaks of Ebola, which was viewed as an ‘out of Africa’ disease of “people who have contracted the disease…have done so in…cave area, where the monkeys hang out” (Leach, 2008, 8). HIV was associated with Haitian Americans so much so that it was called “the 4H disease,”- a reference to the perceived risk factors of “Haitians, homosexuals, hemophiliacs, and heroin” users (Marc et al., 2010, 1).

Such narratives led to the stigmatization of not only the infected individuals but the community at large, the members of which in other countries were evicted from their homes, and a number of them suffered unexplained job losses (Farmer, 1999, 106). Interestingly, the source of rationalizing in these cases is not grounded in science but is “anchored in a particular historical moment” (Scheper-Hughes and Lock, 1997, 7), which situates the disease in the existing structures of social relations and divisions within a given society.

India fighting corona

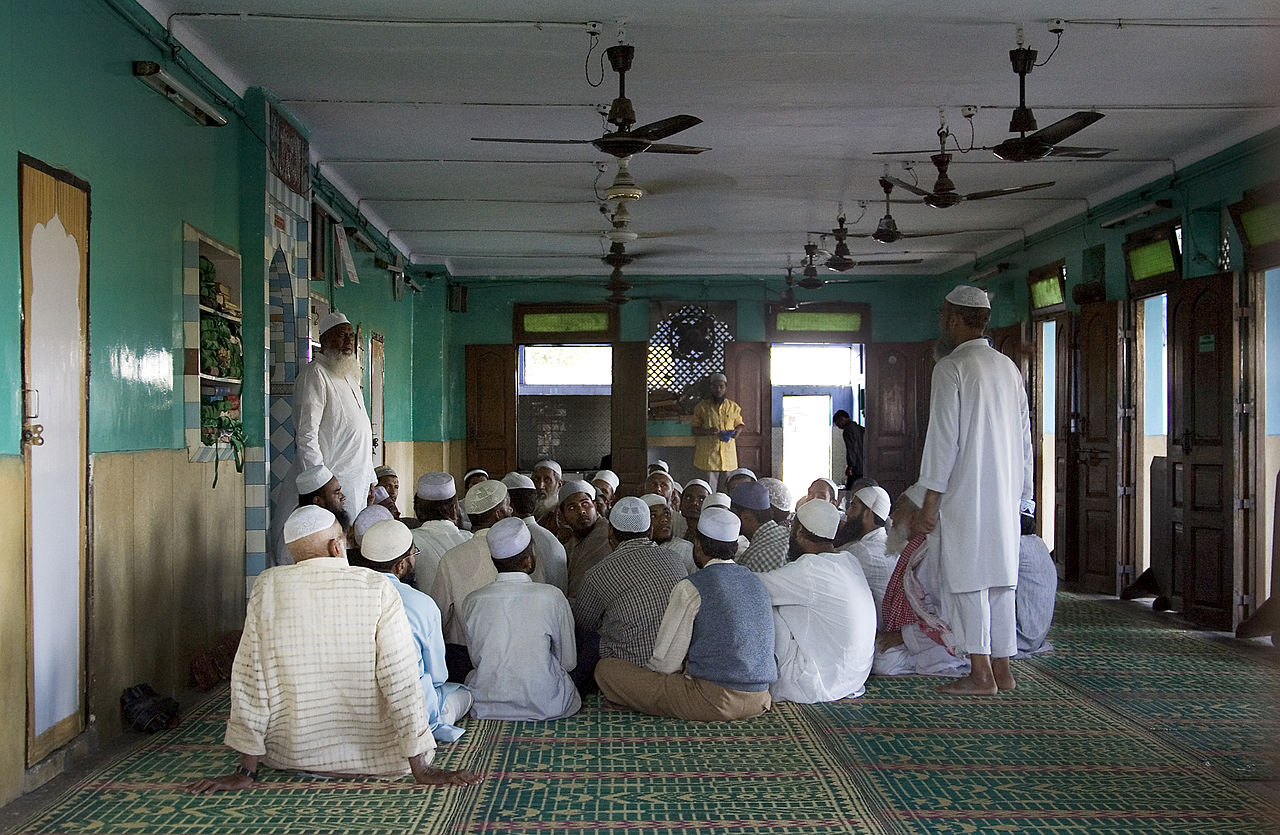

Amidst the corona pandemic, this pattern is taking a communal shape in Indian society. This can be traced to the moment when the information of coronavirus infections began to surface from New Delhi’s Nizamuddin, where a Sunni religious group called Tablighi Jamaat had gathered for their annual congregation in mid-March. A wave of fearful fury took over the nation, and members of a single community were soon seen as “superspreaders,” i.e., ones responsible for the spread of the virus in India.

In the situation of a national lockdown where a large majority of the population is confined to homes, major sources of information are broadcasting media and social media. Many news channels, consistent with their pre-corona repute, are reporting the news with the familiar Islam-hating rage, ignoring any nuances to the mentioned incident. There even appeared a narrative of bioterrorism, which suggested that the members of the congregation were involved in implanting the virus across the country, and demanded an end to the “corona jihad”.

Politicians from the ruling BJP and other leaders from the Hindu-nationalist side appeared on these platforms. They made accusatory claims, demanding a ‘manhunt’ of the infected members, therefore reinforcing the demonization of the Muslim community. This single-minded reaction is part of the history of communal tension in the country, the most recent memory of which is the introduction of the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) of 2019 leading up to the Hindu-Muslim riots in Delhi.

As indiscretion and irresponsibility are being reported as intentional in the case of Jamaat transmission, there’s growing stigmatization of the infected and of the community at large. Circulation of social media messages and videos vilifying Muslims, increasing incidents of suicides, mob lynching, threats, and harassment of Muslims are being reported from across the country. So much so that lately, posters like “no Muslim trader is allowed into the village till the coronavirus has completely gone away. Signed: All Hindus, Kolya,” have shown up on the walls of a village.

As revealed in the cases of HIV and Ebola, blame communication that portrayed the local population as ignorant and mired in traditional practices furthered the complexities of controlling the spread. The narrative of blaming along with the history of discrimination by the west (slave trade and colonialism) in both cases developed counter-narratives of distrust, thereby turning them defensive, hostile, and violent. The distrust manifested itself in people’s disbelief toward the spread of the disease, which was seen as a conspiracy by foreign governments (Saez et al., 2014; Wigmore, 2015; Selzer, 1987). These accusations were not baseless rumors but echoed the suffering of the past like the scandal around the selling of Haitian blood and plasma for a lower price to American laboratories (Farmer, 2006, 239).

With the CAA backlash just a few months old, it should not be too surprising that many Indian Muslims distrust the State more than ever. The blame communication is resulting in cultivating the already swelling resistance within the Muslim community. This is becoming explicit where controlling measures of isolation and quarantine are actively opposed, especially in Muslim neighborhoods. In cultures that have not experienced epidemics previously, the concept of quarantining, especially during illness, is already unheard of.

Moreover, in Indian cultures, the care of the sick is family-centered. What complicates the situation is a community’s distrust in the medical and State administrative authorities handling the crisis. For one to be able to surrender their health to a system they do not trust while also being ‘physically distanced’ from the family, it is not an easy task. As seen in cases of previous outbreaks, the same invites resistance when forced. The cases of medical resistance to testing and treatment, misbehavior with and attacks on medical workers, hiding, and non-reporting can be analyzed in the context of mistrust of Muslims in the Indian state, furthered by media blaming, which rather than helping curb the pandemic, is only making it worse.

Breaking the cycle of stigma and bad communication

On the one hand, there are structural-historical factors contributing to the current landscape of conflict between the State’s response to the medical crisis and the Muslim community’s reception of it. On the other hand, there are the media-led forces of communication that are amplifying the conflict. There exists no prescriptive cure for structural inequalities the way there exists one for an ailing communication response.

In the Indian case of COVID-19, therefore, we propose that while the deep history of communal tension cannot be erased, what can be dealt with is its aggravation right now. Hence, an inclusive response to the crisis must also involve intervention in the quality of communication, one that must be careful not to add to the panic, resistance, and violence. It is only possible to strategize in this way if the consequences of blame and accusation are realized, and the need to step back from the same is considered necessary to mitigate the pandemic.

References

- Farmer, P. (2006). AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. University of California Press.

- Leach, M. (2008). Haemorrhagic Fevers in Africa: Narratives, Politics and Pathways of Disease and Response, STEPS Working Paper 14, Brighton: STEPS Centre, 1-23.

- Marc, L. G., Patel-Larson, A., Hall, H. I., Hughes, D., Alegría, M., Jeanty, G., … & Jean-Louis, E. (2010). HIV among Haitian-born persons in the United States, 1985–2007. AIDS (London, England), 24(13), 2089.

- Saez, A. M., Kelly, A., & Brown, H. (2014). Notes from Case Zero: Anthropology in the Time of Ebola. Notes. [online] Available at: http://somatosphere.net/2014/09/notes-from-case-zero- anthropology-in-the-time-of-ebola.html [Accessed 29 April 2016].

- Scheper‐Hughes, N., & Lock, M. M. (1987). The mindful body: A prolegomenon to future work in medical anthropology. Medical anthropology quarterly, 1(1), 6-41.

- Selzer, Richard. (1987). A Mask on the Face of Death. Life 10(8): 58-64.

- Wigmore, Rosie. (2015). Ebola Anthropology Platform.

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

Readers' Reviews (1 reply)