Diversity and Exclusion in school classrooms – A pertinent concern

Dr. Jyoti is a professor at Delhi University.

Ekta Yadav

Ekta Yadav is a BElEd IVth year student at the same department specialising in mathematics education. She is pursuing a school-based undergraduate research project on learning trajectories followed by diverse students.

This article is based upon the authors’ school internship experiences in an urban metropolitan primary school, located in South Delhi, where the classrooms were akin to a melting pot of students from diverse sociocultural backgrounds. This internship is a part of their pre-service teacher education.

Diversity is inherent to the human condition. Yet paradoxically it is not too visible in school classrooms, at least on the surface. Teachers don’t, often enough, attempt to bring it to the fore.

Among the reasons for this ambivalence towards student-diversity is the presumption that in an urbanized cosmopolitan context of a metropolis the children’s backgrounds are broadly homogenous especially with reference to language, culture and everyday practice. For instance, it is assumed that children in a metropolitan classroom of a typical school in North India will belong to neighboring states like Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar, the so-called ‘Hindi belt’. That the students will have adequate familiarity with the Hindi language and its associated cultural nuances.

The slogan unity in diversity is often invoked to emphasize not only the threads of connectedness related to the common cultural heritage of people of this region but also implicate a common educational framework for schooling of our diverse children. Notwithstanding this connectedness, the vast region of North India is home to an array of cultures, languages, knowledge systems, traditions and family practices. It is inhabited by several regional, cultural and ethnic groups belonging to varied communities making for a multiplicity of social groups nurturing their distinct languages, epistemologies, festivals, holiday observances and cultural practices.

Language is a key aspect of this diversity. In education this is vital as language is a major tool for learning, thinking and knowledge construction among young students. The medium of instruction in several government school systems in North India, across many states, is Hindi. There is often one section of students taught through the english medium especially in schools that are in a so-called higher tier of a school system for example some of the Pratibha Vikas Vidyalaya run by the Directorate of Education, Government of NCR of Delhi. This is despite the rich presence of several regional languages such as Punjabi, Haryanvi, Bengali, Urdu, Bhojpuri, and Maithili. A delhi resident also comes across Telugu, Tamil, Kashmiri and Gujarati speakers. Yet the authors, in their long association with school education, have not come across any schools where any of these languages are the medium of instruction. These languages are the home-language of some of the residents in the Delhi metropolitan region. There are hardly any textbooks, curriculum frameworks or teaching-learning resources on which a primary education in any of these languages can be provided.

A news report from the state of Maharashtra was poignant in this regard. This report was of the lone Gondi-medium school in the entire large state of Maharashtra, which was running classes from grades I-VI, closing down in this January by an executive order of the Education Department, State of Maharashtra (IE, 2025). It is noteworthy that this was the only school educating students in the language of the Gond people residing mainly in Gadchiroli district of the state. Even though the state board of education neither has a Gondi curriculum nor Gondi-textbooks but the school borrowed Gondi texts from the neighboring states of Chhattisgarh. The mere existence of this school kept the language, its epistemology and cultural heritage alive or at least represented in a formal educational system. As per 2011 census around 4.5 lakh people in Maharashtra and over 29 lakhs across India speak the Gondi language.

School education fails to adequately foster such regional and less socially dominant languages since tend not to be the medium of instruction. This marginalization of some of the languages like Gondi can be understood by a term proposed by language educators: pyramidal structure (Panda, 2022). The term refers to language practices in school systems. The practices are so organized that they have turned into a structure that supports ‘a monolingual education system in which when more than one language was used, the languages appeared hierarchically, and consequently home language disappears quite swiftly in favor of regional language; and national language in favor of other international languages. The number of options related to language studies decreases as children go into higher levels. Such an approach is not conducive to the preservation of indigenous and endangered languages (Raina, 2022:82). Had the Gondi language been a prevalent language practiced as a medium of instruction the pyramidal structure, leading to closure of the Gondi medium school may not have developed.

Mapping diversity

A school contact programme is an integral component of pre-service teacher education. The authors have been associated with a government primary school in South Delhi, a cosmopolitan site, for 45 days in the final year of their four-year teacher education programme. The school is a Kendriya Vidyalaya (KV) which offers scope for exploration of student-diversity because of its pan-India clientele. The avowed mission of this school system is to cater to the educational needs of children of transferable Central Government employees including defence and paramilitary personnel who are posted in different places in the country from time to time. They are attended by many students who have migrated from other regions of the country. To this end all the schools run by Kendriya Vidyalaya Sangathan (KVS) provide a common programme of education, all over the country.

Diversity in the classrooms was evident in our teaching work at the KV, located in a residential government neighborhood in South Delhi, where we interned. The school, like all KVs, is run by KVS and has been designated as PM Shri Kendriya Vidyalaya which made available a host of grants and additional facilities for this particular school. Our observations, interactions and teaching in the school reflected that the classroom was a melting pot of different cultures, languages and ideas. We present the profile of two students from this school as examples of the heterogeneity inherent to human diversity but tend to homogenise in the school classroom due to prevailing curriculum practices.

Student profile 1

Porishmita (pseudonym) is a nine-year-old student of grade IV. She belongs to Assam and has her early upbringing in that state. Her mother tongue is Assamese. She has a great deal of proficiency in Assamese language which she can speak, write and read in. At home she converses with her family in Assamese. She also speaks English fluently and is an avid communicator in the English language as well though is not very proficient in writing in English. Her rather low socioeconomic family status can be gauged by the fact that she does not have access to a computer or internet at home. Her parents are supportive but have limited educational capital and intellectual wherewithal to scaffold her with school-based homework. Her family emphasizes traditional values of their state which was revealed to us when she shared that they celebrate regional festivals like Katibihu (prayer for good harvest and family welfare) and Me-Dum-Me-Phi (ancestor worship). .

Alienation from the classroom

Porishmita is hesitant to participate in some of the classroom activities, involving unfamiliar culture practices like north Indian major festivals. Among the reasons for this is her personal and communitarian alienation from the dominant north Indian cultural practices – for example the manner in which major festivals are celebrated and the foods that are associated with celebratory ceremonies. Revdi and Gajjak that are essential knick-knacks of Lohri celebrations for instance, are not common in her home state of Assam.

Her peer dynamics also impact her classroom motivation, confidence and behaviour because as she does not align with the social background of most of her classmates. In the caustic words of one of her classmates, ‘She is not our friend because she prefers to speak in some other language, English or Assamese and we are Indians, and she is not’. This was an acerbic though flawed comment because the classroom should be a space to forge oneness notwithstanding social differences. What is further noteworthy is that she is not conversant with Hindi which is the sole medium of instruction in the classroom. Linguistic diversity becomes the basis for not only suffering exclusion from her peer group but also inability to comprehend Hindi which is also a school subject. All of these factors contribute to her alienation from the rest of the class.

Student profile 2

Birbala (pseudonym) is a 10-year-old girl attending grade IV. She is from Jharkhand, and her mother tongue is Santhali. She can speak and read the language but is unable to write in it. She has been living in Delhi for the past three years. She understands Santhali very well, including its embedded meanings, as it is her native language. Being from a Santhali-speaking region, she also has knowledge of the cultural symbols associated with the language. She is fluent in Hindi, which she can read, write, and speak, and it is also taught as a school subject.

Birbala’s struggle lies with the English language, which she cannot speak or understand when it is taught in the classroom. She is unable to write in English, which makes written paper-and-pencil tasks a significant challenge for her. She finds it difficult to comprehend English lessons and cannot read aloud as most of her classmates do. She lacks a real-life context for learning English, as no one in her family or immediate community speaks the language. She comes from a low socioeconomic background and lives in a rented single room in a neighborhood near her school in New Delhi. Her father works as a security guard in a residential colony, while her mother stays at home. Although she has access to technology, with two mobile phones owned by her parents, the devices are not of educational value to her, as she does not have the skills to use them for learning or to access information or resources.

Birbala’s worldview

Birbala has rich knowledge of cultural traditions of her own community as she knows Santhali language which is replete with epics, stories and folklore; especially related to the native festivals of Santhal region like Sohrai which expresses gratitude to the gods by everyday activities like cleaning the home, singing and dancing.

She has remained connected with her roots but experiences a cultural gap in some of the dominant school practices including festival celebrations that tend to have a north Indian urban flavor in tonality as well as content. She also experiences a sense of alienation in the classroom due to her struggles with learning English, which leads to poor performance in English as a school subject. The high status that English holds further exacerbates her sense of failure, negatively impacting her self-esteem and contributing to her low achievement. Ironically, while Porishmita feels socially isolated from her classmates, who are fluent in Hindi and English, Birbala faces a different challenge altogether—she is unable to learn English due to her complete lack of knowledge of the language.

The spectre of English

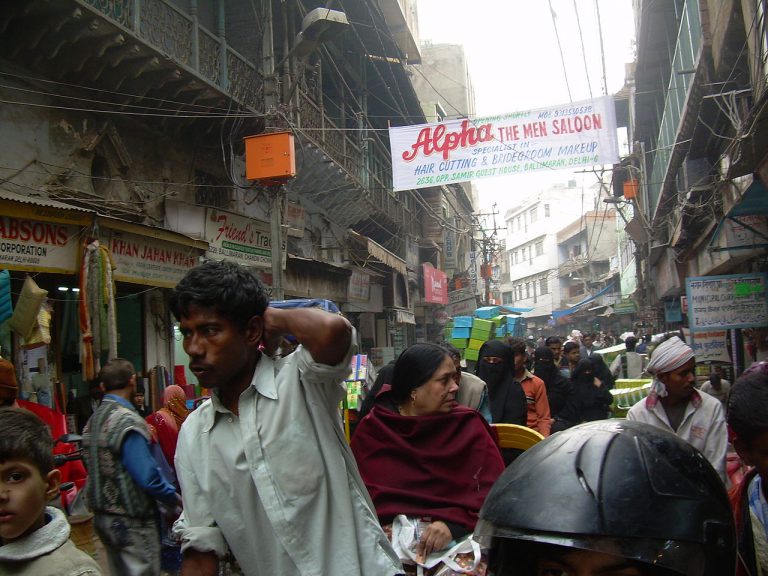

The educational policies since independence have recommended that primary education be imparted in the child’s mother tongue but practice bellies policy even in the capital of the country. Even government school’s tom-tom as English medium institutions as if being an English medium school were a magic wand of education as the picture above shows. Anyone can second guess what this means for a student like Birbala. Inclusion necessitates a multilingual education rather than learning English approach as is pointed out by educationists (Tiwari teal. 2017).

Consequences for student diversity

In this metropolitan classroom when students like Birbala and Porishmita speak different languages and embrace different worldviews; how can they be presumed to learn like the other students who come from relatively homogenous, urban socio-linguistic backgrounds?

If classrooms are neither multicultural nor multilingual nor inclusive, then can students in their individual capacity be held responsible for poor learning?

The classrooms of our school system have not incorporated the worldviews of children from diverse communities especially those who are relatively on the margins like Birbala and Porishmita. The centralized curriculum of most school systems of our country do not provide adequate space for including multiple knowledge, ideas and languages of our world which is a pluriverse.

The school classroom is a melting pot of diverse students who need nurturance in a multicultural and multilingual education, which is not available in schooling. Therefore, the social differences manifest as disparities in achievement across social backgrounds. These need to be viewed not just as poor learning or gaps in school achievement across social disparities but also as different learning trajectories of diverse learners.

References

- The Indian Express. (2025, January 19). Maharashtra’s sole Gondi-medium school faces closure. https://www.indianexpress.com

- Raina, J. (2022). ‘Inequality in education: Towards a consensualisation of the status quo’. Book Review of V. Gupta, R. K. Agnihotri, & M. Panda (Eds.), Education and inequality: Historical and contemporary trajectories (pp. 79–88). Social Scientist, 50(3–4).

- Panda, M. (2022). The state, market, and multilingual education. In V. Gupta, R. K. Agnihotri, & M. Panda (Eds.), Education and inequality: Historical and contemporary trajectories. Orient Black swan.

- Tiwary, M. K., Kumar, S., & Mishra, A. K. (Eds.). (2017). Dynamics of inclusive classroom: Social diversity, inequality, and school education. Orient Black Swan.

- Tiwary, M. K., Kumar, S., & Mishra, A. K. (Eds.). (2023). The social context of learning in India: Achievement gap and factor of poor learning. Routledge.

The article resonates deeply with me, as it highlights the challenges faced by students from diverse sociocultural backgrounds in urban classrooms, particularly due to language barriers. Having studied Marathi as a second language, I can relate to the experiences of Porishmita and Birbala, who feel alienated because of their linguistic differences. Their struggles remind me of my own experience—learning Marathi in school but not using it later in life, which created a disconnect from my cultural roots.

Language is more than just a tool for communication; it shapes identity and influences learning. The dominance of Hindi and English in many schools often sidelines regional languages, making students from non-dominant linguistic backgrounds feel isolated. I have personally felt this marginalization, realizing how language plays a crucial role in shaping one’s sense of belonging.

To build a more inclusive educational environment, schools should actively integrate regional languages into the curriculum and celebrate linguistic diversity. Encouraging multilingual education would not only help students like Porishmita and Birbala feel more included but also strengthen connections to one’s cultural heritage. By recognizing and valuing every student’s linguistic background, we can create classrooms that foster both academic growth and a deep sense of belonging.

This article really made me think. It sheds light on how students from diverse linguistic backgrounds often face challenges in classrooms where the primary language of instruction differs from their own. Many times, these struggles go unnoticed, making it harder for them to feel fully included.

While reading, I was reminded of a student from my 7th-grade class—a Tamil boy who is fluent in English and Tamil but struggles to communicate in Hindi. Until now, I hadn’t consciously realized that I should make certain modifications in my teaching approach to ensure he feels comfortable and included, not just in terms of language but also culturally. It’s not that I didn’t want to or wasn’t aware of the importance of inclusivity, but this article served as a much-needed reminder.

It has made me more mindful of how language barriers can impact a child’s sense of belonging. As educators, we need to create a space where every student, regardless of their linguistic background, feels seen, valued, and included. Thank you for this insightful piece!

This article beautifully highlights the challenges faced by students from diverse socio-cultural and linguistic backgrounds in metropolitan classrooms. It sheds light on the often-overlooked struggles of children like Porishmita and Birbala, who experience alienation due to the lack of recognition of their languages, traditions, and cultural practices in the school system. I feel the author’s emphasis on the need for a multilingual, multicultural, and inclusive educational approach is a crucial reminder that the existing educational frameworks must adapt to the reality of student diversity. By incorporating a more inclusive curriculum that values all languages and cultures, we can create a more equitable and supportive learning environment. Personally I think this article is a call to action for us to rethink the concept of inclusion and work towards a truly diverse and fair educational system. This perspective offers hope for creating a classroom where every student, regardless of their background, feels valued and empowered to succeed.

This article highlights a crucial issue, how schools fail to accommodate linguistic and cultural diversity, leaving students feeling disconnected from their own identities. As a student-teacher, I have encountered many students like Birbala and Porishmita, struggling to find space for their mother tongues in the classroom.

And it’s not just about the students I teach—it’s personal. I have felt this too. My own mother tongue, Punjabi, has slowly faded into the background of my thoughts. At home, it is the language of my family, my roots, and my earliest memories, but in school, it was replaced by the dominance of Hindi and English. Over time, I felt the disconnect growing, I could understand my mother tongue, but I stopped thinking in it, stopped reading it, and eventually, stopped feeling it the way I used to.

Schools often prioritize being “English-medium” over meaningful learning, leading to rote memorization rather than true understanding. Students who struggle with English are seen as weak, even though they possess deep knowledge in their native languages. Instead of treating multilingualism as a barrier, education should celebrate it—allowing students to bring their languages into the classroom and connect with their learning in a way that feels like home.

“I thoroughly enjoyed reading this article, as it highlights the significance of inclusive education in today’s diverse classrooms. The author’s emphasis on teacher training and inclusive curriculum is particularly noteworthy, as these are crucial elements in creating a welcoming environment.

“I also appreciate the author’s focus on practical strategies for creating inclusive classrooms, such as using inclusive language and providing opportunities for student reflection, is particularly useful.”

This article does a great job of highlighting how language plays a crucial role in both inclusion and exclusion in education. Through the stories of two students—Porishmita, who speaks Assamese but struggles with Hindi, and Birbala, a Santhali speaker who finds English difficult—the authors bring out the real-life challenges faced by linguistically diverse students. These personal narratives make the issue feel urgent and relatable, showing how the rigid education system often isolates students instead of supporting them.

One of the most insightful points in the article is the explanation of the pyramidal structure of language in schools. The way home languages get replaced by regional and national languages, and eventually by English, is not just about communication—it’s about erasing cultural identities. This shift forces students to adapt rather than allowing them to thrive in their own linguistic and cultural spaces.

As someone who has experienced the realities of Indian classrooms, The struggle of students to fit into a standardized system, often at the cost of their own identity, I found the discussion incredibly relevant.

I also appreciated the article’s use of the phrases melting pot and magic wand. The melting pot metaphor is fitting—students from different backgrounds are brought together, but instead of blending smoothly, some identities get overshadowed. The magic wand phrase, used humorously, perfectly captures how schools treat English-medium education as a quick fix, ignoring the deeper need for inclusivity.

Overall, this was a thought-provoking read, but it left me wanting more in terms of solutions. The article identifies the problems well, but how can schools actually create a multilingual, inclusive space for students? That’s the next question we need to explore.

This article highlights an important issue—schools in cities often overlook the rich diversity of students’ languages and cultures. Even in North India, where many languages like Punjabi, Urdu, and Bhojpuri exist, Hindi is the main medium of instruction, leaving other languages unrecognized. Since language shapes learning and identity, schools should embrace this diversity to make education more inclusive and meaningful.