Revisiting Sunshine: How my reception of this movie changed

Johnny Rich, in his book The Human Scripts, wrote that “To reread a book is to read a different book. The reader is different. The meaning is different.” The same goes for visual content as well, I believe. Revisiting old movies, series, or incidents always brings in with it a new perspective of viewing it. But I was not as staunchly reminded of it in the recent past as I was by rewatching the movie ‘Sunshine.’ Having last seen it years ago, I experienced it in a completely different light. The last time I had watched it, I was in my twelfth standard, at sixteen, and mostly did not have the mental capacity then to view it through the lenses I did now. Having watched the movie now, as an adult, and also as an amateur movie enthusiast, I cannot help but wonder just how many thinking points the movie provides us with and how incredibly underrated it really is. This post is not my review of the movie but just me expressing my awe for the movie and realising my artlessness in my viewing of it the first time around.

On the surface, Sunshine is a 2007 British sci-fi movie written by Alex Garland and directed by Danny Boyle with chilling sound design and majestic cinematography, that tells the story of a group of scientists who are on a mission as humankind’s last hope of saving it. Set in 2057, where our Sun is dying, and so is our planet, Earth has used up all its remaining resources to make an experimental, stellar, nuclear fission bomb with the mass equivalent of Manhattan island that the team is supposed to set off at the surface of the Star to help reignite it. The international team aboard the spaceship Icarus ll (foreshadowing its doomed fate and a reference I did not get the last time around), the second such mission after the failed Icarus l mission seven years prior, comprises of eight astronauts, each of whom is an eclectic expert in a different field and have unique personalities. How they act and react in the wake of an accident leading to a catastrophic chain reaction is mostly what the film is about.

In my first viewing of it, this is precisely what I saw. A movie set in space, with characters from all over the globe, facing a problem never faced before by humankind, set into motion by an avoidable error. And that was it. I do not remember thinking about it days after having seen it, something that happened this time around. Enough to make me want to write about it. Sunshine does seem to borrow elements from previous space set sci-fi movies like Aliens, 2001:A Space Odyssey, and Solaris. Like most sci-fi movies, this too was not free from scientific inaccuracies, but the ability of the film in tackling the emotional, physical, and psychological instability of the crew brought on by extended space travel and being humanity’s last hope in addition to the game-changing accident, was something remarkable and has stayed with me.

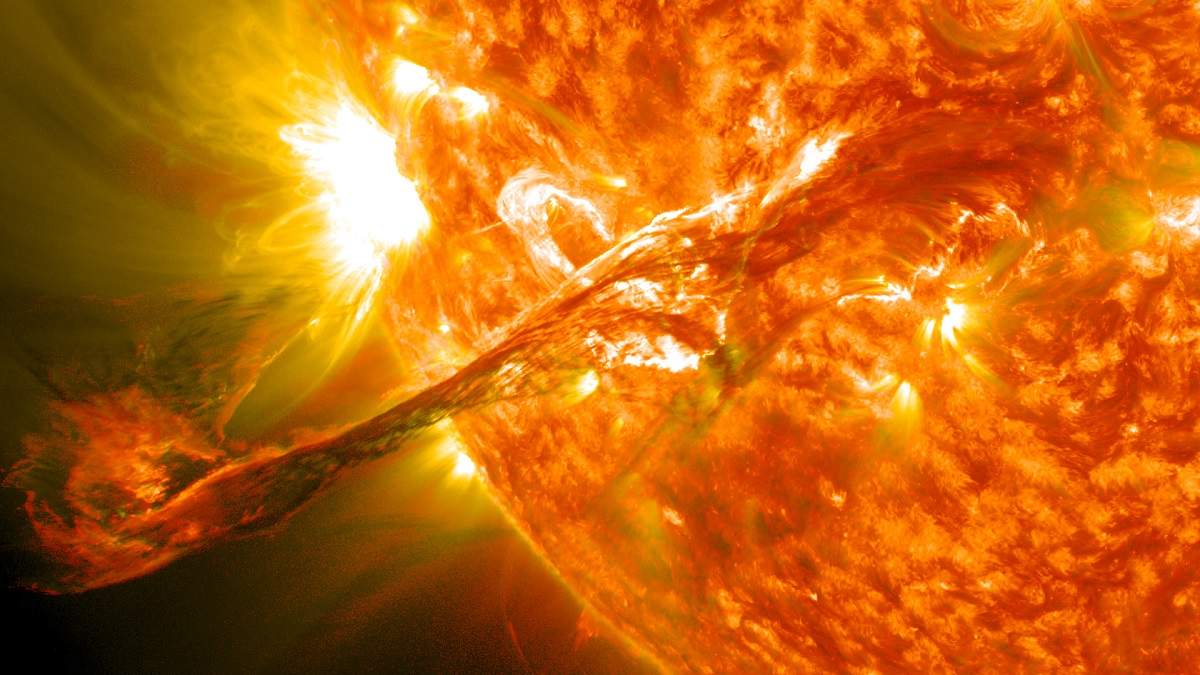

It becomes fairly evident early on that the Sun is a metaphor for God, who is currently dying, and so the Earth is dying with it. Come to think of it; in some sense, the Sun literally is our God. Not only does it give us life, but it also sustains it. Life on Earth is not possible without the Sun. The whole concept of the Sun giving us life and we using that life to give meaning to the Sun is explored in the movie in a manner I have not seen in recent times. The movie gives us a visceral and innate experience of our relation to the Sun. The initial sequence of Searle in the observation room shows us just how profusely fierce and inconceivably violent the power of the Sun is. Despite being millions of miles away, we are unable to look at it directly. Carl Sagan’s quote from the Pale Blue Dot -“It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.” comes to mind while watching the scene of the Icarus ll crew watching Mercury from the observation room as they slingshot past it. The scene also magnifies this feeling by showing the crew who have mostly been arguing and disagreeing, sitting stunned and silent at the sight of it.

One of the best things for me about Sunshine was its fully realised characters. The eight crew members are Capa, a physicist; Kaneda, the ship’s captain; Cassie, the pilot; Mace, the engineer; Corazon, the biologist; Searle, the psychologist; Trey, the navigator and Harvey, the communications officer in addition to Icarus, the ship’s AI and Pinbacker, the captain and the sole surviving crew member of Icarus l. Each of them has different attitudes and outlooks. Each of them is pragmatic and rational, yet seldom in agreement. Some are completely driven by logic, facts, and science, and are also ready to kill their crew members for the sake of humankind, whereas there is also someone who is a religious fanatic to the point where he most probably killed his own crew and definitely tries to kill the crew of Icarus ll to stop them from completing their mission. A parallel of sorts is drawn between religious fanaticism and scientific fanaticism.

While the faith versus science trope is one regularly frequented by the sci-fi genre, something about it in Sunshine really stayed with me. We are shown both how a spiritual attitude can turn into religious fanaticism (with Pinbacker) and how a non-believer, when in fear, can turn into an egocentric, entitled person who can no longer accept reason (with Harvey). Through the characters and their belief systems, we see how both spirituality and atheism leads to people rationalising killing other human beings (Pinbacker and Corazon) and also leading to humility and to them committing acts of selfless bravery (Searle and Mace).

How in the face of constant reminder from the universe, either by the grandeur of the Sun in its power or the cold vacuum of space, of the insignificance of our lives, we can still appreciate the sanctity of life and how we do not necessarily need God or religion to be amazed by the cosmos, was something that I saw in the movie for the first time. The movie made me embark on an introspective viewing adventure where, in the face of a new hurdle, I, as the audience along with the crew, questioned whether I would make the same decisions as well, given that the fate of humankind was in the balance. I was struck by how unapologetic the movie was in its asking questions regarding weighing the lives of the people on board. In the bigger picture of humanity, they are all expendable, but how do you have that conversation? How do you tell someone they are less important to the survival of humanity even if they do know it themselves at some level?

The crew, composed of an assortment of characters, come to terms with how tiny humankind is and how grand the Sun is, in their own way. This fact also makes its way on to the screen when a human error turns the journey of the astronauts into a trip they cannot return from. While it still remains uncertain if their mission would be a success and thus the future of humanity saved, it does become certain that all of them are going to die. Although, as scientists, the certainty of death as mortal beings was known to them, it was still something abstract and not yet close enough to accept as the reality. This forces you to think of the ultimate insignificance of our existence as a whole as well. Pinbacker’s quote, “At the end of time, a moment will come when just one man remains. Then the moment will pass. Man will be gone. There will be nothing to show that we were ever here, but stardust.” makes you ponder on the eventual and incontrovertible mortality of humankind.

In both the crews, we get at least one person who begins to view the Sun as God, Searle on Icarus ll, and Pinbacker on Icarus l. Although still unclear if Pinbacker killed his crew or they chose to end their lives willingly, he strongly believes that the Sun is God and that God has decided to end human life, and we should and could not argue and fight it. On the other hand, the spaceship and the bomb attached to it uses science to reach and try to reignite the Sun and save mankind. The final scene of the movie has Cillian Murphy’s character Capa literally standing between the Sun (the God) and the exploding bomb which is supposed to reignite it (the Science), and in some sense, the visuality of the scene makes it look like faith and science meet and greet each other. The movie makes you question who are we, mortal beings, to begin with, to fight extinction? Can the science this mortal being has developed help us beat or save the God that created us? And if it does, does that not make us God ourselves? And if yes, is that hubristic or inspiring?

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia