The root of oppression does not bloom Equality: Feminism beyond Inclusion

Saurabh Suman is a master’s student in Transcultural Studies at Heidelberg University, Germany. His research interests include culture, gender, and politics. During his leisure time, he enjoys cooking, music, and poetry.

The society which is inherently exclusive and fractured along varied discriminatory lines, inclusion fails to serve justice and, at best, can only defer it. In times when feminism is commodified by capitalist appropriations, siphoning lucre through the marketing of inclusion, the chasm between justice and inclusion demands the extension of feminist struggle to fundamental change beyond illusory inclusion.

As Audre Lorde asserts, “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”. We must not be beguiled, even for a moment, into thinking that societal acceptance marks the end of the feminist struggle for justice. Society, like snakes molting to survive, sheds its skins—or, more aptly, recolors them—to protect its institutions, whose heart is cemented with inequality and oppression, from the threat of irrelevance and, at worst, potential extinction.

Exclusive Inclusion (T&C apply)

Inclusion, practiced within the shadow of pre-existing understanding of identities, at best acknowledges gender as a social construct but leaves the underlying power dynamics untouched. One may argue that inclusion provides historically excluded sexes the opportunity to put forth their perspectives and reclaim, or rather claim, their spaces within society and its institutions. But then, above all, the process of inclusion becomes crucial to track. Inclusion, which I call exclusive, comes with costs, terms, and conditions. Who decides these terms and conditions? The cost these terms and conditions add to inclusion surpasses its perks, thus making it an exclusive commodity. As Hilary Silver, in her essay “The Process of Social Exclusion,” writes, “The flip side of active exclusion is the important stress on active participation in one’s own inclusion.”[1] Wherefore, participating actively in the process of one’s own inclusion in feminist struggle means withdrawal from the process itself, because, as is evident, this “inclusive representation” in no way promises the redistribution of power by dismantling the system that engendered the exclusion of “not men” at the outset.

The glass must fall: Beyond reflected equality

In Lapata Ladies, Manju Maai, a fierce and tall feminist, in one of her monologues, says, “dekhne jaaye toh aurton ko mardon ki kono khaas zaroorat hai nahin, par ee baat agar aurton ko pata chal gayee toh mard bechaara kya baja na bajaayega.” (“Women don’t really need men at all, but if all women figured this out, men would be screwed, wouldn’t they?”)[2] She highlights men’s illusion of superiority over women, resulting in a supposed mandatory women’s dependence on men, which a patriarchal society, with all its possible nuances, fabricates. A male-dominated society not only makes women dependent, yielding inequality, but also sets the rules for their struggle against inequality, keeping the ‘sanctity’ of male centrality untouched.

Women, historically, have been othered, defined as deviations from men, as ‘not-men’. “She is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other.”, writes Simone de Beauvoir in the introduction of her book The Second Sex.[3] Tokenistic equality—including women in male-dominated spaces and paying them ‘equally’ to men—has no caliber to restructure the fundamentally oppressive and patriarchal system bottom-up. It may be a need of the time, but it doesn’t serve the ultimate pursuit of women’s liberation. Therefore, it becomes important not to grant men the privilege of being the standard for equality. The failure to do so not only perpetuates the preconceived notion of women being the Other but also hinders the scope of change, which is foundational rather than symbolic.

Capitalist Feminism—An Oxymoron

Capitalism—a system of men, for men, by men—smelling the threat, began packaging of their inherently exclusionary products in the guise of feminism. A ‘modern’ man yearning for an ‘independent and homely’ woman on a matrimonial website is the ideal capitalists’ lackey of feminism. For capitalists, ever the opportunists, feminism is nothing more than a tool for exploitation and the extraction of profit.

Irigaray, in her book This Sex Which Is Not One, in a chapter titled “Women on the Market,” draws on the Marxist theory of “exchange-value” to explain the status of women in society, arguing, “Women are thus always defined in terms of their use and exchange established by and between men.”[4] Further explaining “use value” and “exchange value,” she highlights how society positions women parallel to any commodity that is exchanged and used in a capitalist society, and so too women in a (capitalist) patriarchal structure. Is inclusion, therefore, enough? A mere place at the ‘table’ cannot deliver justice, but only the illusion of it. The question remains: A place on whose ‘table’? The system—unchallenged—of men will continue ‘using’ women.

Intersectionality at the heart

Intersectionality suggests that not all inequalities are born equal, ergo, equality cannot be a singular, universal ideal. The effect of patriarchal oppression cannot be generalized, nor can its impact on a world that is hierarchically diverse be deemed uniform. More crucially, while we demarcate or categorize distinct forms of inequality, there are some people who are subjected to an overlap of these. For instance, the historical weight of exclusion and injustice carried by the LGBTQIA+ community is often greater than that experienced by many other groups, and intersecting social constructs like sex, gender, caste, class, race, and nationality can layer upon this burden, making it unimaginably unbearable. Therefore, while questioning the utility of inclusion in the feminist struggle for justice, it is important to acknowledge that inclusion itself can be ultimate ‘justice’ for those marginalized even within ‘mainstream’ feminist discourse.

As we dive deep into intersectional feminism, it clearly is noticeable that advocating on behalf of others is often outright rejected. Moving beyond symbolic representation, individuals take agency into their own hands; for example, an ‘upper caste’ lesbian will not voice for a dalit lesbian, who is expected to take on her own fight head-on. Drawing upon the discourse of intersectional feminism, it is evident that even if someone achieves inclusion—what they may have aimed for—they will remain subject to a fundamentally unjust system that remains unchallenged. Thus, apparently, dismantling the very foundation of the patriarchal system remains a crucial step towards ultimate equality and justice.

From root to bloom

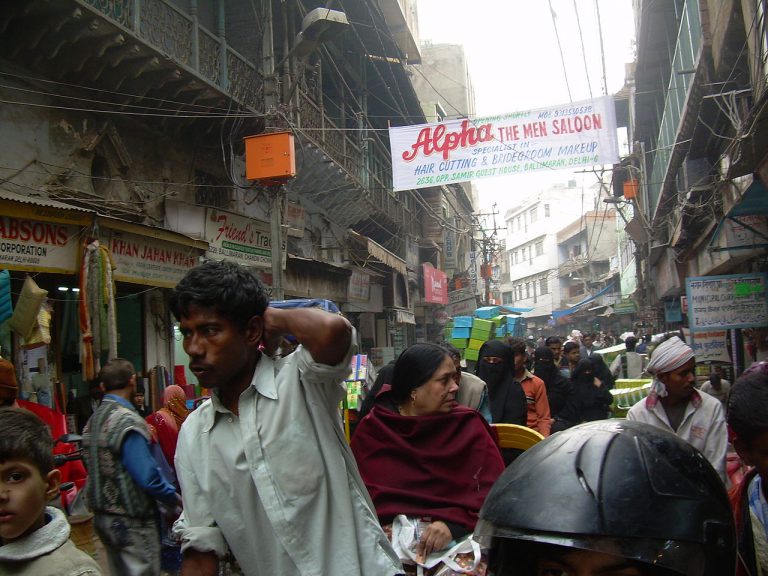

Debating inclusion in a country where tribal women are paraded naked and the Supreme Court rejects same-sex marriage pleas can sometimes seem pitifully ignorant and worthless.[5][6] But we cannot turn away from the fact that all this happens in the proud nation where the presidential chair ‘includes’ a dalit woman. Amidst the bombardment of red herrings of inclusion, the struggle for change, uncompromised, often gets devoured by its shroud of smoke. So, what may pose a question to moving beyond this narcotic inclusion in the pursuit of the feminist dream may itself bring the very need for such a move to the fore.

The time has come for feminists to exclude ‘inclusion’ from their hall(s) of struggle and build their own ‘table(s)’ for the feast of equality. When asked, ‘Are women equal to men?’ we, with our heads held high, must reply, ‘No, they are not. Nor should they be. Men are not someone that women should be equal to.’ The root of oppression does not bloom equality.

References

- Silver, H. (2007). The process of social exclusion: The dynamics of an evolving concept (CPRC Working Paper No. 95). Chronic Poverty Research Centre. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1087789.

- Rao, K. (Director). (2024). Laapata Ladies [Motion picture]. Jio Studios; Aamir Khan Productions; Kindling Pictures.

- de Beauvoir, S. (1949). The second sex (H. M. Parshley, Trans.). Vintage Books. (Original work published 1949).

- Irigaray, L. (1985). This sex which is not one (C. Porter with C. Burke, Trans.). Cornell University Press. (Original work published 1977).

- Press Trust of India. (2023, October 16). CBI files murder charges against 6, minor in Manipur horrific video case. NDTV. https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/cbi-files-murder-charges-against-6-minor-in-manipur-horrific-video-case-4486716.

- Sharma, P. (2023, October 17). Supreme Court refuses to recognize same-sex marriages, asks Union Govt to form committee to determine rights of queer unions. LiveLaw. https://www.livelaw.in/top-stories/supreme-court-same-sex-marriage-equality-queer-couple-240341.