Media representation of COVID 19: Power and media

The declaration of the disease caused by the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) as a pandemic by the World Health Organisation created a surge of news articles on the newly discovered virus worldwide. Earlier, what was declared as a local outbreak, in late December, had then developed as a threat to global public health by March. Even the social media was hit by a storm of tweets and posts about what the virus meant and when social distancing measures would go away.

In times of crisis like the current pandemic, the role of the mass media and the social media should be analysed since they play an important role in the formation of public opinion as well as being the main source of information for many. In this essay, I will use a Foucauldian lens to analyse the role of national media. The essay will also try to critically contrast the application of Foucault’s theory to the media with Noam Chomsky’s Propaganda Model of the media as representing the elite interests. This will be followed by a conclusion and the role of social media and why such spaces should be protected.

After the lockdown was initiated in India, the Muslim community became the centre of media attention after it emerged that six people who died from COVID-19 in southern Telangana had attended an event held by a Muslim religious group from March 13-15 in New Delhi. A large part of the mainstream media made the entire Muslim community responsible for the spread of coronavirus in the country. This led to widespread resentment against the community among many, and social media posts with problematic stances appeared.

Power, according to Foucault, was not a property but a strategy consisting of “manoeuvres, tactics, techniques, functions.” In Discipline and Punish, Foucault asserted that power is not a unilateral system from above but marked by an interaction of forces. He also asserts that power and knowledge are interdependent as “power produces knowledge, that power and knowledge directly imply one another” (Foucault, Discipline and Punish 54). Power, according to Foucault, is both productive and repressive, and while it creates knowledge, it is also reinforced through knowledge. In The History of Sexuality, Foucault creates a link between power and discourse. Discourse to Foucault is about the process of the transmission of knowledge and how bodies of knowledge are created and controlled by it (Foucault, The History of Sexuality 54). Discourse then serves as a transmitter and producer of power, while simultaneously, it potentially undermines and exposes power.

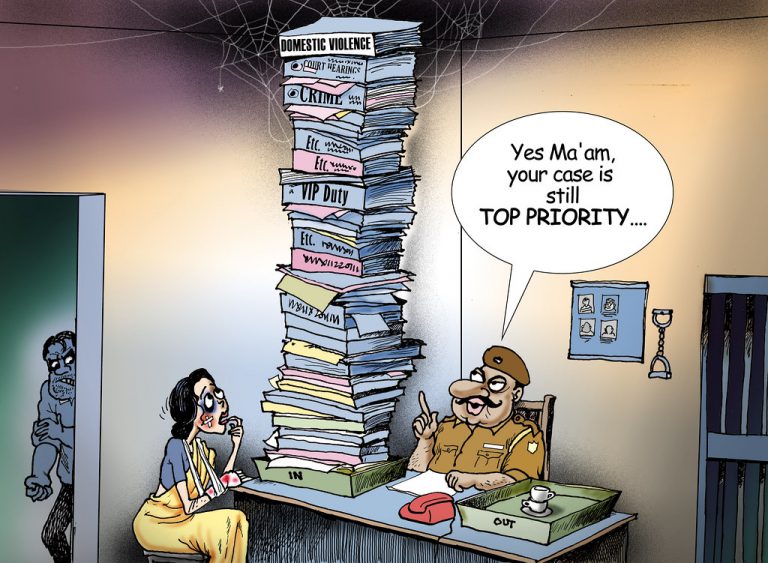

Public debates are replete with examples of influences of the mass media and its ability to shape public opinions. Mass media is an institution that creates content for communicating it to an extended audience. Thus, if we refer back to the understanding of discourse by Foucault, the mass media is an institution that produces discourse and communicates knowledge on a wide range of issues in the public sphere. Thus, the COVID-19 reporting and vilifying an entire community as the cause of a certain disease should be put to question. Here the power of the media is to define the public’s sense of the social reality of the society they live in. The media creates knowledge and distinguishes between what is truth and what is false. It creates this with the use of such narration, images, and proofs that fits their agenda. Foucault stresses that truth cannot be understood as something that lies outside the ambit of power or lacking in power, but rather as produced and reinforced by power. Even when the blaming of a certain community is empirically incorrect, the mainstream media houses organise a panel discussion to propagate the truth regime subscribed by them.

Yet, one must remember that power, according to Foucault, is not unilateral. When the public at large is communicated through such an understanding of social reality, it must not be understood as a one-way process. In the case of the Indian mass media, if one observes closely, there can be no dominant discourse but rather a multiplicity of discourses. There are numerous examples of media reports which opposed such sectarian views. Even the social media reacted to the mass media reports in a variety of ways – some accepted the view while many opposed it. Thus, Foucault asserts that a multiplicity of discourses are present in the world. Each opinion which got generated in the social media acted as a means to construct knowledge through power as well as propagate power through the construction of knowledge. It is only through the unpacking of such varied discourses, one can understand what is said and what is concealed, who is speaking, and the institutional context in which the speaker is situated.

Power to Foucault was also not only repressive but also productive. Thus, whether it is public concerns about the spread of coronavirus by a certain community that constructs the reports of the mainstream media or the opposite is hard to establish. Foucault would say it is a little of both. Thus, Islamophobia, which was propagated by certain social media accounts, also shaped how the mainstream media constructed its reporting.

According to Noam Chomsky, “the media will present the picture of the world which defends and inculcates the economic, social and political agendas of the privileged” (34). Thus, the mass media will only reflect the perspective of the elites (which the government is a part of) but not public opinion because of the ideological barrier present within it. Chomsky also asserts the role of the alternative media but, at the same time, asserts that it lacks the resources and reach like the mainstream media.

It may seem grim at first if one uses the lens by Chomsky at a time like the pandemic when the mainstream media sometimes become the only source of information. But a Foucauldian understanding of power and media can be a silver lining since, unlike Chomsky, power to Foucault and the construction of knowledge can come from multiple sources. The social media (Foucault may argue it is a virtual panopticon) is the source of exerting power and introducing a variety of knowledge during the pandemic. Even if there are multiple instances of fake news propagated in social media platforms, multiple cases also show how citizen journalism amplified such voices that had been marginalized by the mainstream media. Social media thus became the alternative media in India and around the world at the time of the coronavirus pandemic and a means through which many could construct knowledge through discourses.

References

Chomsky, Noam. Understanding Power: The Indispensible Chomsky. Edited by John Schoeffel and R. Mitchell, First Edition, 9th printing, London, The New Press, 2002.

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish. Translated by Alan Sheridan, Harmondsworth, Netherlands, Penguin Books, 1979.

The History of Sexuality. Translated by Robert Hurley, London UK, Netherlands, Penguin Books, 1990.

Featured Image Credits: Flickr