Learning to teach: Nuggets from a primary school classroom

Three young beginning teachers and their educator explore possibilities in a primary grade classroom. Fiza Gauri, Ekta Yadav and Zarqa Shafi are BElEd IVth year students.

Ekta Yadav loves exploring backstories, finding power and development of comic characters as fun and fulfilling.

Fiza Gauri is a passionate educator, blog writer, and a reader and aims to inspire young minds through creative storytelling and informative content. Her teaching expertise is in English and Science.

Zarqa Shafi observes, experiments, and tries to create engaging lessons that make learning fun. Her areas of interest are Mathematics and Science: igniting young minds, one lesson at a time.

The aesthetics inherent in a bottom-up, open-ended, and lightly framed pedagogical approach are valuable in learning to teach. This article is based on the internship teaching experience of three beginning teachers in the fourth year of their initial teacher education program at a women’s college in New Delhi. The school they intern in is located in the urban metropolis of south Delhi. Their approach to teaching lays special emphasis on language development, particularly on the student’s home language and mother tongue. Such approaches become valuable as each educational policy in the history of independent India has recommended that primary education till grade V be provided in the student’s mother tongue.

Educational policies have also recognized multilingual education as an instrument of cognitive enrichment that enables students to become better learners. The twin ideals of mother tongue-based education and multilingual education have received a renewed thrust in National Education Policy 2020. Language teaching practice, however, belies this policy intent because of the systemic constraints upon school education. Two or more languages are part of the school curriculum as components of a tightly framed examination-oriented curriculum. Their teaching in the classroom is often an outcome-based process in which aspects of language are often reduced to textbook sections separated as literature and grammar with an undue focus on information and coding-decoding of text for regurgitation in the examination.

Language teachers often follow a tightly framed methodology of taking up textbook questions and answers mainly in a paper pencil mode. Against this background, bottom-up, open-ended, and lightly framed somewhat unconventional pedagogic possibilities of language teaching offer an aesthetic and meaningful learning opportunity. Three such scenarios are discussed in the rest of this piece.

Scenario 1: Discussion followed by simulation

A language lesson in grade IV was planned using storytelling as a pedagogical tool to engage students. The story, from the school textbook, titled Naseeruddin Ka Nishana, author not mentioned, is about the exploits of a maverick named Naseeruddin who is always seen boasting about his archery skills in front of his friends (NCERT, 2021). He often missed his archery targets and liked to make excuses for the same. One day, he managed to strike a designated target in his third attempt, which amazed all his friends and gave him ample room to brag. A discussion and a simulated magnetic dart game followed up this story narration.

The post-narration discussion began with the teacher asking students for their responses to the story. The student responses were based on their personal experiences and brought student voices into the classroom. The classroom became a forum for self-expression, confidence building, and stroking a student’s imagination. Some of the student comments during the discussion are as follows:

- Naseeruddin was very clever no matter what other people may say.

- I also like Naseeruddin love playing nishane vali games.

- Pubgy game mein bhi aise hee nishana lagate hain.

- Naseeruddin was merely bragging. He really didn’t know any archery.

- Naseeruddin hit the target by accident, his first two aims were missed so he put the blame on his friends just like one of my boastful friends always does.

- Naseeruddin was lying when he missed the target, facetiously saying he was showing how his friend aimed at targets. He was a liar.

A game similar to the one played in the story in the lesson was simulated using the blackboard akin to a magnetic dartboard game. It added interactivity to the lesson and students were elated to play the game. Select comments during the game include:

- My nishana is the best.

- I will do a Naseeruddin, cook an excuse, if my shot will miss.

- We play like this in other archery games too.

- Two friends to one another: When our turn will come, you act as Naseeruddin and i’ll be his friend. Unless you hit the shot right.

- We used to play nishane vala game with slippers and soft balls in our village.

- His (pointing towards his friend) shot is just like Naseeruddin, just missed by one inch.

- Girls don’t play these types of games. (But soon the girls proved the child wrong by participating and in fact hitting the aim).

However, this open-ended, loose and bottom-up approach offered classroom aesthetics of social interaction, communication, self-expression, imagination, and language learning. The students connected the story from the vantage point of their own experiences and shared these perspectives. They were excited to participate and encouraged to speak in any language they enjoyed, and their comments revealed a sense of companionship, cooperation, and creativity. The game also helped to break down gender stereotypes, as girls actively participated in a so-called boy’s game and even scored well.

Scenario 2: Two activities

A lesson in an English textbook for grade IV titled Don’t be afraid of the dark (NCERT, 2024) described the life and work of deaf-blind American author and disability rights advocate Helen Keller (1880-1968). The lesson was introduced with two brief whole-class warm up activities.

The first activity involved, speaking without speaking, where the students were asked to shut their eyes for a few seconds and imagine what it would be like if one isn’t able to speak. They were then asked to express their thoughts and feelings about this brief experience. Select responses are as follows:

- I thought of Helen Keller. She could not see or hear but she could feel. She had emotions and feelings just like us.

- She was able to listen her inner voice because of the silence outside.

- I have felt frustrated and angry at other students because they didn’t understand what I want to say.

- Helen Keller feel connected with Miss Sullivan (her teacher) because she teaches her and most important she understands Helen’s feeling and needs.

The second activity aimed at experiencing darkness around oneself. The students were instructed to just close their eyes, imagine total darkness and attempt to gain self-awareness. Student’s responses were as follows:

- I am so scared because there was a wolf’s shadow behind me which is too terrorizing.

- I felt alone it’s a very horrifying moment for me.

- There is a possibility of being kidnapped. It scares me.

- I am feeling cold.

- I was in a dark night, sky full of stars and half-moon and walking alone in a narrow street which is covered with trees on both sides and cold air wave touched my arms and face.

- I saw purple flowers all around.

The two activities were planned to explore possibilities in language teaching that was pleasurable, as in the first one, and humanising as the second experience turned out to be. Bringing such aesthetics of experiential learning in the classroom, through such introductory activities, is motivational for beginning teachers who are learning to teach as it prepares a base from the bottom-up; on which to make meaning of the given lesson in a relatively open manner.

This open-ended approach draws from two conceptual resources in language education. The first is that of multilinguality (Agnihotri, 2021) which believes that language is not a static object or a school disciplinary subject to be acquired by classroom instruction alone but rather ‘consisting of a wide array of fluid and diverse linguistic entities’ (Raina, 2022). Language is also an aprabhasha distinct from formal, somewhat standardised language often dominating a school classroom. The notion of aprabhasha offers possibilities in the classroom.

In the primary school where the above-mentioned teaching nuggets are drawn from, one is from a Hindi lesson and the other an English lesson; both the languages are part of school curriculum as formal subjects. The teaching approach in the two activities encouraged children to simply express themselves without worrying about sticking to speaking in one language only at a time or using a formalised language. This was facilitative as the students were freer to frame their thoughts in words without worrying about the mixing of languages.

The second pedagogical resource comes from the field of language learning which has proposed a new theoretical concept: multilingual intelligence (Panda, 2022). In formal school learning where the medium of instruction is often different from the student’s common language, there is a demand upon their cognition to shift between one or more languages, invoking multilingual intelligence. This leads to the development of several cognitive characteristics among students including fluidity, flexibility, expanded working memory, metacognition and a worldview emphasising connections rather than separation (Panda, 2022).

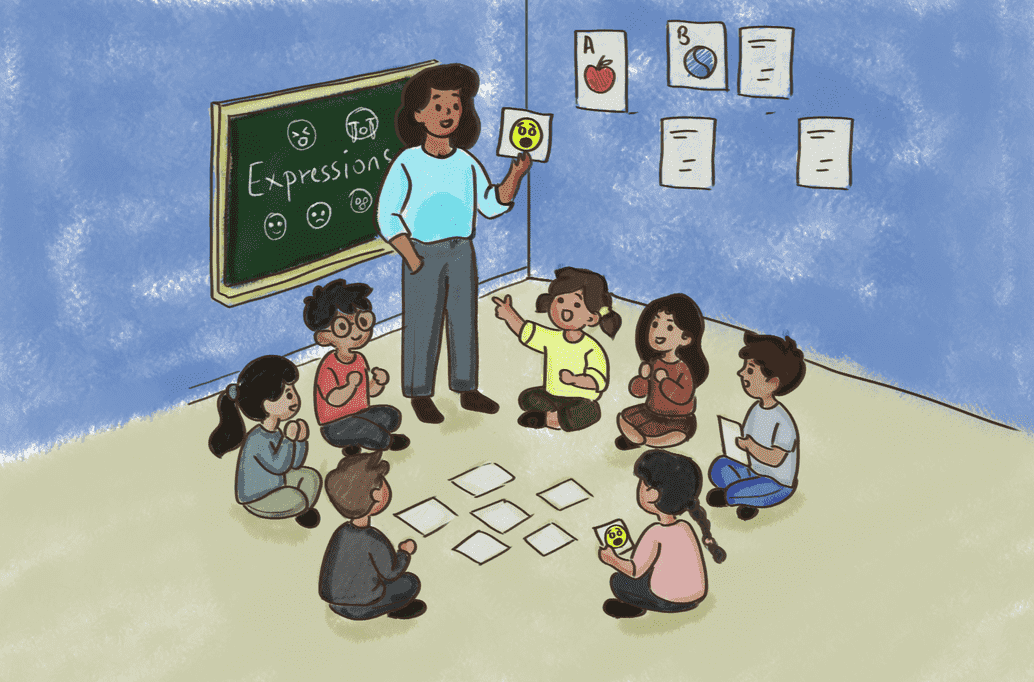

Scenario 3: Talking Maths

The idea of multilinguality views language as a fluidity which aligns with the belief that language is present across all the elements of curriculum. This is true for school curricula in all grades and across different disciplinary domains. In a mathematics lesson for grade III an activity to teach addition and subtraction following language across curriculum approach was planned. For adding intellectual excitement and to evoke curiosity; it was cleverly titled A Magic Show (NCERT, 2024) to pique the students’ interest and foster engagement. As soon as students heard the title, they began exclaiming, ‘Ma’am sach mai koi jadu dikhane wali hai kya’.

An opportunity was created for students to eagerly participate and discuss the activity among themselves, setting the tone for an interactive learning experience that encourages students to speak in the classroom, in their home language, so as to share their thoughts and ideas.

In this activity, the pencils of 35 students in the classroom were collected by the teacher. The teachers and students counted and noted a total count of the pencils. A student was then instructed to randomly take some pencils and cover the remaining ones with a cloth. The problem task was to determine the number of pencils hidden under the cloth without directly counting or looking at the covered ones. To solve this problem, one of the students suggested counting the pencils that had been taken out earlier and subtracted that number from the total count. This calculation revealed the number of pencils hidden under the cloth. To verify the result, the students counted the hidden pencils as well. The purpose of the pencil-collection activity was: first, to grab the students’ attention, and second, to encourage participation and create an opportunity for them to engage in discussions and interact with each other. The talk that was initiated in the classroom by this activity includes the following student remarks:

- Mere paas pencil hee nahi hain.

- Iske paas pencil hai par issne nahi dee hain.

- Ramesh ke paas bahut saari pencils hain.

- Isne do pencils dee hain.

- To find the total number of pencils just look at the total number of students.

This engaging activity sparked a lively dialogue and facilitated communication among the students. As pencils were collectively counted, the class buzzed with enthusiasm to learn. During the initial count, some students expressed concerns, saying, ‘Ma’am, hamne ek pencil count nahi kari!’ This sparked an animated discussion about the accuracy of the total count. Seizing the teachable moment, the students were guided through a problem-solving process. ‘First, count the pencils you took,’ the teacher instructed. ‘Then, subtract that number from our initial total count.’ This calculation would reveal the number of pencils hidden under the cloth. To verify our result, students were asked to count the hidden pencils. ‘If our calculation matches the actual count, we know our initial count was correct,’ teacher explained. ‘However, if it doesn’t match then simply add the pencils you took to the hidden pencils to determine the exact total number.’

This exercise encouraged thinking, collaboration, reflective abstraction and reasoning as a hands-on, bottom-up and open approach transformed a simple counting exercise into a valuable learning experience. Such activity-based experiences also lead to development of conceptual understanding in mathematics as opposed to procedural knowledge that is often produced by teaching through methods like the carryover procedure for learning addition and subtraction.

These three teaching nuggets reflect the experience of three beginning teachers in learning to teach by planning simple classroom activities. Even in our tightly framed examination oriented school curriculum there is an aesthetic that provides spaces for such possibilities facilitating student and teacher learning.

References

- Agnihotri. R. K. (2021). Multilinguality and challenges to education. In V. Gupta, R. K. Agnihotri & M. Panda (Eds.), Education and inequality: Historical trajectories and contemporary challenges (pp. 322-358). Orient Blackswan.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training. (2021). Rimjhim, Hindi textbook for class IV. New Delhi : NCERT.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training, (2024). Marigold, English textbook for class IV. New Delhi : NCERT.

- National Council of Educational Research and Training, (2024). Maths Mela, mathematics textbook for class III. New Delhi : NCERT.

- Panda, M. 2023. ‘Multilingual Intelligence (MI) and the Politics of Educational Reform’, Krea Psychology Talks, November 24, 2023.

- Panda, M. 2022. ‘Multilingual Intelligence: The Politics of Poverty, Desire and Educational Reform’, Psychology and Developing Societies, 34(2), 287-314.

- Raina, Jyoti (2022). ‘Inequality in education: Towards a Consensualisation of status quo’, Book Review Education and Inequality: Historical and Contemporary Trajectories, Editors: Vikas Gupta, Rama Kant Agnihotri and Minati Panda. Social Scientist, Volume 50, Numbers 3-4, March-April 2022.

Engaging read! A strong reminder that teaching is a continuous path, not a final point. – Teach with kindness and imagination – See through the lens of students – Be open to surprises

Motivating read for all the teachers!

The 2nd activity which developed sensitivity in students was extremely impactful and will provide children with an experience which they usually do not experience in their everyday life.Though i feel that the title of the 2nd activity should have been more accurate and should have provided us with a better glimpse of the activity.

Upasna

Thought-provoking article! The ‘nuggets’ shared highlight the importance of relationships, inclusivity, curiosity, flexibility, and embracing mistakes in primary school teaching. Reminds us that teaching is a journey, not a destination.

– Teach with empathy and creativity

– Learn from students’ perspectives

– Embrace unpredictability

Inspiring read for educators

The activity 3 is very insightful and worth attraction right from the name “talking maths” and the idea and the scope it provides for interplay and interraction between maths and language .

I really appreciate your article and it’s really fascinating specially the parts you mentioned different activities. In Scenario 1 , The activity you have done by making them feel like people who can’t see and hear , and that’s really amazing and appropriate activity to create empathy. Whereas , it’s an short , sweet and worth-it.

First, They nicely used standardised language for each particular domain

The way they use NCERT Book chapter for activities with students enroll meant

“This article beautifully captures the essence of teaching and learning in a primary school classroom. The author’s reflective practice and willingness to share their experiences provide valuable insights for both novice and seasoned educators.

It highlighting the importance of:

1. Building relationships and trust with students.

2. Creating an inclusive and supportive classroom environment.

3. Encouraging curiosity and inquiry-based learning.

4. Embracing flexibility and adaptability in lesson planning.

5. Recognizing the value of mistakes and failures in the learning process.

I particularly appreciate the emphasis on:

– ‘Teaching as a journey, not a destination’

– ‘Learning from students’ perspectives and experiences’

– ‘Embracing the unpredictability of teaching’

These nuggets serve as reminders that teaching is both an art and a science, requiring creativity, empathy, and continuous professional growth.

Thank you for sharing your experiences and inspiring fellow educators to reflect on their own practice.

Activities that help students connect with the lesson emotionally and develop empathy. The 2nd activity, where students imagine not being able to speak, helps them understand how it feels and share their thoughts. These activities make learning more fun and allowing students to feel and think more deeply about the lesson.

Zoya

This article shows a creative way of teaching language by using activities that help students connect with the lesson emotionally and develop empathy. The 2nd activity, where students imagine not being able to speak, helps them understand how it feels and share their thoughts. These activities make learning more fun and allowing students to feel and think more deeply about the lesson.

Zoya

Activity 3 provided a good insight in a primary classroom and how activities lead to discussions. How children think and what their concerns are during an activity.- shyla handa