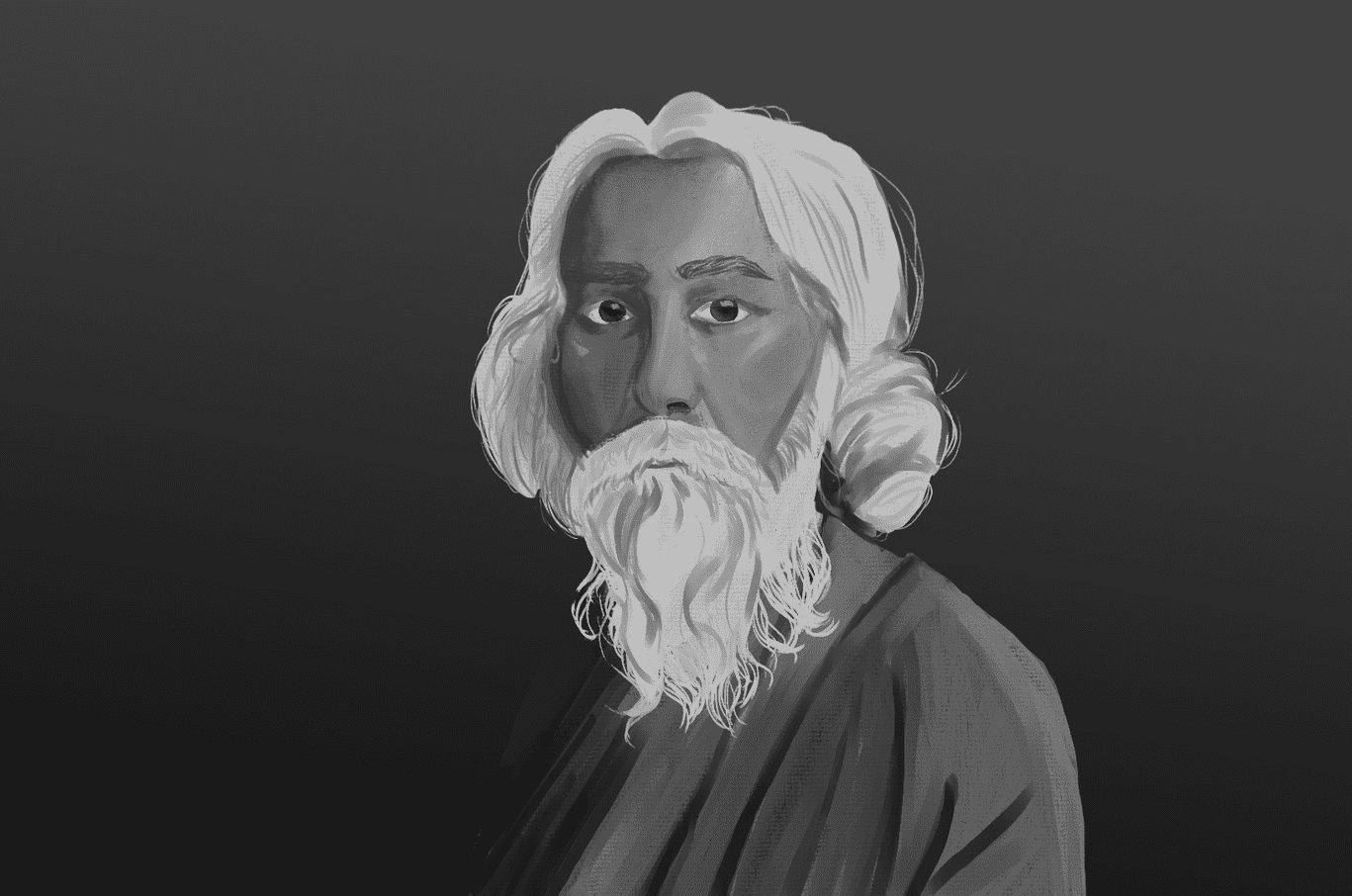

Learning from nature: Rabindranath Tagore’s vision

Dr. Jyoti is a professor at Delhi University.

Ayushi Sharma

Ayushi is a B. El. Ed IVth year student at the Gargi College. Ayushi is an aspiring educator passionate about child psychology, focused on inspiring young minds by connecting concepts to nature and their surroundings.

In this article the authors share their school contact experiences on observing that school students were not encouraged to explore connections with the natural surroundings which prevent children from learning from nature in a meaningful way. To Rabindranath Tagore this was essential to not only experience the unity of truth in this world but also to children’s wholesome development.

The story written by polymath Rabindranath Tagore, that is particularly insightful for understanding education, is ‘The Parrot’s Training’. It is a tale of educating a bird who sings but is otherwise ignorant. The king of the province in which the bird lives recruits the best of scholars for his education. To start with, the scholar-teachers decide to get the bird a cage made of gold. He is taught through astute methods, replete with countless books and lessons providing him with an intellectually stimulating environment. One day the king’s officials announce that the bird’s education is complete. Encouraged at the completion of his order to educate the bird; the king goes to meet him only to find that it cannot hop or fly anymore. On a closer look he notices that the bird’s wings are clipped. In fact he had passed away. Nobody seemed to even know how long the bird had been dead.

This story is symbolic of what’s wrong with the education system in our society. Tagore criticized the education system for ignoring child nature, the way the bird’s education ignored who it was, its true nature and swadharma. Instead of nurturing the bird’s natural abilities, the education system imposed an intellectual education that was indifferent to the bird’s nature. It robbed him of his freedom to fly and hindered its growth to the extent that it could not even remain alive.

The second author had a first-hand taste of the parrot-in-the-cage metaphor of education as she embarked on her school internship in the fourth year of her teacher education study. She was assigned to one of the state-run school in the salubrious environs of south Delhi. The students were caged by classrooms, syllabus, books and related implements. The school has a magnificent garden that would attract any passerby. However, students were not encouraged to go there, not even during lunch hours. When she wanted to take the children to the inviting garden as part of a mathematics activity to find round objects in the garden, the principal refused to allow it during teaching hours. She then thought of assigning it as a task for them to do during lunch time but was surprised to learn that the children aren’t even allowed to leave their classrooms during the lunch hour! The teachers of the school mentioned that this is because they need to attend to eating their tiffins. Moreover, playing in the garden may lead to a fall or an injury. She realised that students were simply prohibited from being in the garden. In the previous year of her study, she had read Tagore’s essay My School in which he writes that ‘The young mind should be saturated with the idea that he is born in a human world’(Tagore, 1996, p. 390). In this essay he emphasized on how learning through nature is a key process of education. This to him was the path of what he considered as the aim of education explaining which he writes, ‘The highest education is that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence’ (ibid).

Contemporary school education is the converse of what is taught to student-teachers in educational studies courses and the aim of school education is mainly to enable children to serve the needs of an information-heavy examination system and acquiring specialization in some field. Emphasis on structures like a tightly framed time table in modern city settings such as the one in which the school mentioned above is located cut young students off from learning from nature. Tagore writes,

“Naturally the soles of our feet are so made that they become the best instruments for us to stand upon the earth and to walk in. From the day we commenced to wear shoes, we minimized the purpose of our feet (Tagore, 1996, p. 392).”

Describing his own childhood aspirations to become one with nature, Bashabi Fraser, Director, Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies writes in 2018,

When Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941) was a little boy, he longed to step out into the wide world and experience nature, but his early memories are of confinement within Jorasanko, the sprawling Tagore family home in Calcutta. He would watch the outside world through the shutters of their great French windows, from the balcony and terrace, admiring the trees, marvelling at the freedom of little boys diving into the pond outside, fascinated by the women filling pitchers or washing clothes and ducks swimming without a care in the world there. (Frazer, 2018, p. 9).

It was while sitting under the trees, in continuity with the natural world that learning could occur. To Tagore, the city schools with concrete rooms were simply not acceptable as a site for his own children’s education. When the time came,

He moved with his wife and young family to Santiniketan, the ‘Abode of Peace’, and began his school at the ashram established earlier by his father. Rabindranath admired the tapovan, the forest hermitage schools of ancient India, where teacher and students stayed close to nature, sustained by the natural environment, with sowing, harvesting and gardening being part of the lived experience of a holistic education. (Frazer, 2018, p.10).

Tagore’s essay expresses the seed idea for this very school with emphasis on setting it up as a secluded natural habitat far away from the non-natural city landscape. The essay is in fact the transcript of a lecture delivered in the United States of America in 1933. An Indian Social scientist J. M. Kumarappa’s 1928 Ph.D dissertation, at Columbia University in the USA was based on Tagore’s writing on education. It was titled ‘Tagore’s experiment in the Indianisation of education,’ while being supervised by the foremost philosophers of education of that time, John Dewey and W. H. Kilpatrick. Dewey has articulated a philosophy of his own in the celebrated 1929 essay My Pedagogic Creed which remains influential to date, yet did not hesitate in guiding a doctoral student on an alternative innovation in education. In our own department during the teacher-education program, student-teachers have been inspired by Tagore’s educational vision (https://armchairjournal.com/journey-inwards/, https://armchairjournal.com/five-educators-on-education/).

More than a century after its inception, the Santiniketan till today continues to offer a physical space, consisting of a central university, more than a dozen schools, and centres of study, that become part of students’ consciousness. Vishva-Bharati, the university, has been designated as an institution of national importance. All of the schools are affiliated to certification bodies like West Bengal’s School Education Boards among others. This marks the continuity of Tagore-founded institutions with the rest of the country’s education system. These schools have kept Tagore’s timeless vision alive with practices like life-centered education, rural reconstruction while according primacy to literature, culture, and the performing arts. Learning from nature is a key aspect of each of these practices. Change of seasons for example is an enthusiastic celebration on the school campuses highlighting the value of nature observation. Like any other illustrious institution established by an iconic writer, all of these are much sought after by the parents of young children, across varied sections of society, in and around Birbhum district of West Bengal. However, the impact of Tagore’s educational ideas, which are an important inclusion of teacher preparation courses all over the country is minimal, as our school internship experience shows.

Re-visiting the school mentioned at the beginning of this article, the aspiration for teaching in a way that young students can engage with their salubrious surroundings such as the garden that was out-of-bounds for the students; the value of learning through observation and simply being with nature becomes paramount for us as educators.

References

- Tagore, Rabindranath. 1996. The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore / 2, Plays, Stories, Essays. New Delhi: Sahitya Akad.

- Fraser, B. 2018. ‘Foreword’ in ‘Rabindranath Tagore and the Environment’, Vol. 2, Gitanjali and Beyond, Edinburgh Napier University, The Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies.

I really enjoyed this article! Tagore’s vision of education emphasizes the importance of connecting with nature, which is often overlooked in today’s schools. The story of the caged parrot perfectly illustrates how rigid education can stifle creativity and curiosity. We should definitely incorporate more outdoor learning experiences to help students grow both academically and personally. Nature can be such a great teacher.

As a reader, I find this article very interesting and thought-provoking. It highlights how today’s education system often focuses too much on exams and textbooks, leaving little room for creativity and exploration. The story of The Parrot’s Training by Rabindranath Tagore is a powerful example. It shows how forcing learning in unnatural ways can harm growth instead of helping it. The parrot, just like many students today, loses its freedom and true nature because of a rigid system.

The author’s personal experience during a school internship makes the message even clearer. Despite having a beautiful garden, the students were not allowed to go outside, not even during lunch breaks. This shows how schools can sometimes block opportunities for children to connect with nature, which is essential for their overall development. Tagore’s ideas about education, especially learning from nature, are very important. He believed that real education helps students grow in harmony with the world around them, not just memorize facts. This article is a reminder that education should nurture curiosity and creativity. It inspires me to think that schools should provide more opportunities for students to explore and learn from the world outside the classroom.

This insightful article highlights the importance of connecting with nature in our education system. Tagore’s vision of learning from nature is truly inspiring. I completely agree with the author’s observation that our education system often neglects the importance of nature and hands-on learning experiences. We need to incorporate more outdoor activities and project-based learning in our schools.

Being a student of B.El.Ed we have been taught the importance of the education which includes hands on learning experiences and when we use them in our classroom the result is always fantastic, children not only learn the concept but take interest and participate to learn more.

By doing this, we can create a more holistic and engaging learning environment that prepares students for success in all areas of life.

The article beautifully connects the parrot’s training to the current issues of our education system.

It focuses on competition, rote memorization and how the system has a one-size-fit-all approach towards the students. Somewhere in the rat race, the child loses their curiosity and creativity. Hope we can learn from Tagore’s teaching and bring change in our education system.

The article powerfully contrasts Tagore’s nature-based education with today’s rigid system, showing how modern schools often stifle curiosity, as seen in the internship example. It leaves me reflecting: How can I, as a future teacher, create space for nature and freedom in a system bound by rules? A strong reminder of the need for education that nurtures both mind and nature.

This article deepened my understanding of the importance of freedom in a child’s life—freedom to explore the world, express themselves, and nurture their creativity. It reinforces the concern that schools today prioritize information overload over fostering a child’s natural abilities. Education has become a race: who scores the highest, earns the most qualifications, or secures the best job. It has strayed from its true essence—gaining knowledge and building skills.

Sharing with my experience-

While teaching tuition to a 4th-grade student, I noticed his syllabus included competitive exam questions (general knowledge, mathematics, reasoning). When I asked about it, he replied, “I need to memorize these questions to clear my exams and outperform my friend with better marks.” This statement made me pause and reflect: Is our education system fair to a child’s natural instincts? In today’s fast-paced 21st-century world, are we forcing children into a relentless competition too early?

Why don’t we allow children to play freely, explore nature, and develop their own curiosity about the world and themselves? Sadly, our classrooms are structured to confine them, restricting their freedom to grow into inquisitive individuals. Instead of letting them spread their wings, we place them in a metaphorical cage, limiting their understanding of the world to a controlled, predefined narrative.

I truly appreciated this article by Rabindranath Tagore, along with the insightful reflections shared by Jyoti Raina ma’am and co-author Ayushi Sharma. Their emphasis on the need to rethink our education system is both relevant and thought-provoking.

– Devanshi

This article presents a compelling critique of contemporary education systems through the lens of Rabindranath Tagore’s pedagogical philosophy, offering thought-provoking insights into the disconnect between modern education and the natural world. Drawing on Tagore’s writings, such as The Parrot’s Training, the authors emphasize the detrimental effects of rigid, exam-focused systems on students’ individuality and holistic growth.

From my perspective, the article effectively highlights Tagore’s nature-centric and experiential approach to education, which feels especially relevant in today’s urban schools. Tagore’s critique of intellectualism at the expense of emotional, social, and spiritual development is strikingly evident in many schools I’ve observed. For instance, one of the authors shares an internship experience at a state-run Delhi school, where students were confined to classrooms despite the presence of a lush garden. This reminded me of my own disheartening experiences during school visits, where children seemed detached from their surroundings, restricted by rigid schedules, and focused solely on rote learning. It’s impossible not to think of the metaphor of the caged parrot from Tagore’s story—students appear to be deprived of meaningful exploration and organic learning.

The article also delves into the broader issues of prioritizing safety, discipline, and academic performance over experiential learning. While these practices may stem from good intentions, they end up limiting students’ opportunities to connect with their environment. I find this critique particularly relevant when reflecting on how modern education emphasizes measurable outcomes—standardized tests and rankings—often at the expense of fostering curiosity, creativity, and holistic development.

One of the most compelling aspects of the article is its discussion of institutions like Santiniketan, which continue to embody Tagore’s vision. These schools demonstrate the viability of an alternative approach, integrating nature into the learning process and nurturing interconnectedness. However, the article doesn’t shy away from acknowledging the challenges of scaling such models. The entrenched focus on exams, urbanization, and rigid curricula present significant barriers. Even though Tagore’s ideas are part of teacher training courses, their influence on mainstream education remains limited.

What I appreciated most about the article is its blend of personal anecdotes, literary analysis, and historical references, which together make a convincing case for revisiting Tagore’s philosophy. It left me questioning the direction of contemporary education and inspired by the possibilities of integrating nature and human values into learning.

It also made me want to explore further: How can nature-based education be effectively implemented in different geographical settings? How can teacher training programs be improved to bridge the gap between theory and practice regarding nature-based learning?

The article critiques rigid, examination-driven education systems, contrasting them with Tagore’s vision of holistic, nature-centered learning. It highlights the restrictive practices in schools, such as limiting access to gardens, and emphasizes the need to nurture children’s curiosity and individuality by integrating experiential, nature-based education to foster their overall development.

“A thought-provoking article that highlights Rabindranath Tagore’s profound appreciation for nature and its role in shaping our lives. You have beautifully woven together Tagore’s philosophy and writings to create a compelling narrative that underscores the importance of reconnecting with nature. A must-read article for anyone interested in exploring the intersections of nature, education, and personal growth.”

The article critiques the rigidity of contemporary education, which prioritizes examinations and information-heavy curricula over holistic development. Also, Drawing from Tagore’s The Parrot’s Training, it highlights the flaws of an education system that suppresses a child’s natural tendencies, likened to clipping a bird’s wings. The authors share their school internship experience, describing how students were confined to classrooms and barred from interacting with natural surroundings, even when beneficial for learning. Under the guidance of Jyoti Raina, Ayushi and her co-authors highlight the importance of rethinking education to blend academic rigor with experiential learning and a deeper connection to nature.