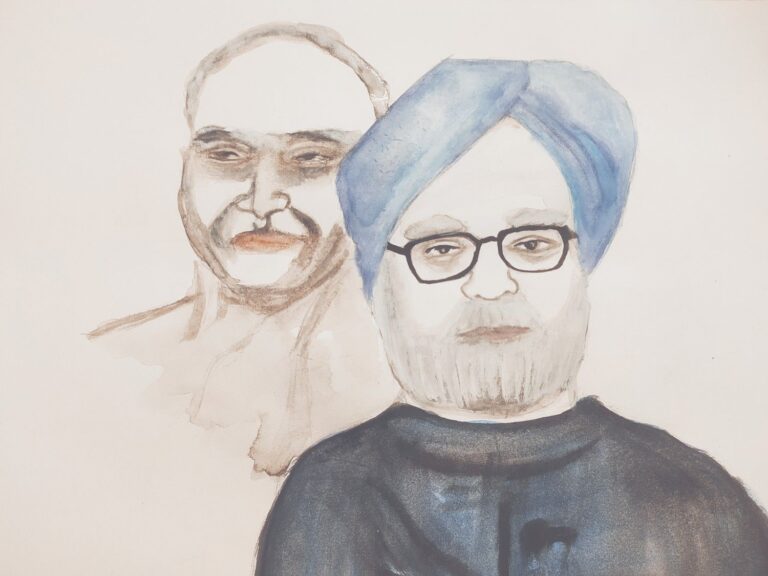

Journey Inwards with Jiddu Krishnamurti, Rabindranath Tagore and Avijit Pathak

Dr Jyoti teaches at the Department of Elementary Education, Gargi College, Delhi University. As part of her pedagogy, Dr Jyoti encourages her students to publish articles in the journal.

This personal essay walks a lane inwards with three great educationists. The vision of the three men provokes an understanding of what is wrong with prevailing schooling practices.

Education involves a search within. In this exploratory quest the three educational philosophers Jiddu Krishnamurti, Rabindranath Tagore and Avijit Pathak have walked the road less traveled. Walking with them in the spirit of a co-traveller enables one to shed the normative framework of what is defined as education in our contemporary society. These thinkers have rejected the prevailing schooling practices for the approach’s indifference to child nature, instrumental objectives, inability to seek higher ideals of life like becoming one with the world. This personal essay highlights how an inward journey with the three extraordinary educationists can develop a vision of a humanizing education. In this process one cannot resist rethinking educational practice or turning into a seeker oneself. This makes the inward walk important for teachers, students and anyone associated with education.

The key element of Krishnamurti’s educational theory is the belief in total awareness essential for a free mind. And the free mind is essential for the right kind of education which aims at an intelligent understanding of the world. He believed that human beings are always learning from their past which is only possible when they look inwards. It was Krishnamurti’s ‘search within’ that throws light on various aspects of human existence that make us human.reading his writings is a complete process of self-awareness. It creates a space for a reader as an individual in the social as well as political scenario. He says, “one cannot know of something unless the other is also present”for example, one cannot know of non-violence unless violence is known. Voicing out the socio-political issues in a habitual state of living, the solutions to those issues lie in total and continual awareness. He argues that all introspection is a form of retrospection. He distinguishes between the personal self and the individual self, a distinction which can be discerned through awareness. Personal self, he defines, is accidental “the circumstance of birth, the environment of upbringing, nationalism, class, and associated prejudices”. This has become the focus of the prevailing education system, with its hierarchies of class, disciplines and even examination marks. Children in contemporary society go to a graded school system depending on their social background. Within the school system they are stratified into hierarchies of subjects and by so called academic achievement markers like examination marks. Such an education merely seeks to train our minds without achieving completeness, integration of thought and being, or awareness of the self. According to Krishnamurti because of the absence of self-awareness in conventional education systems, independent thinking becomes extremely difficult. The tendency to follow convention and thereby get addicted to approval from others traps young students in a vicious cycle of homogeneity. The young become afraid to be different from the herd, something that kills the spirit of adventure. In this homogenizing process there is a tendency to be like your neighbor, or fellow student; which is no more than a drive to seek comfort and minimise conflict and being as much as possible like the others around us. He writes,

Life is pain, joy, beauty, love, ugliness, and when we understand it as a whole, at every level, that understanding creates its techniques. But the contrary is not true: technique can never bring about creative understanding. Present-day education is a complete failure because it has overemphasized technique (1).

To overcome the fear of ‘being different’ Krishnamurti suggests the path of seeking awareness which is entwined with revolt. This is not the revolt of the revolutionary Marxist but a far deeper but inner revolt. He distinguishes between the violent revolt and inner revolt advocating only the latter which is a profound psychological revolt of intelligence. It enables the young student to transcend established systems, orthodoxies and conditionings. The former can be a trap of falling for other orthodoxies, or, illusions that will again require revolt. The latter is an inner, intelligent revolt which according to him comes with self-awareness, self-knowledge while leading to self-realization.

To the first-initiated reader Krishnamurti’s insights may appear as ambiguous, abstract, and ideal. It may be difficult to agree with everything from his voluminous writings. The reader may be devoid of a mental schema to connect to his writings yet identify with the issues he highlights especially with reference to the current education system. This is the seed of self-awareness and inward journey with him. Whenever the alternate reality through his lens seems far-fetched, a young reader can connect with the realities of their own schooling. Many among us can recollect having been subject to passivity, where homogeneity was expected of young students despite their uniqueness which goes (un) noticed. The young often begin to lose confidence in sharing their views which may be unpopular in the school, thus developing hidden aspects of identity. These hidden aspects in fact constitute the essence of one’s being. The inward walk with Krishnamurti can bring such awareness to the fore even after several years. The rat race where marks are the cheese exhausts many students as a result of which the major part of their schooling is spent away in being unaware of the core self, something that can be overturned partly in this walk on the inner lane.

Bonding with Tagore

For Tagore the legend of eating the fruit of knowledge was not consonant with dwelling in paradise. According to him, the purpose of life that guides the object of education is to give man the unity of truth. Does the school allow young mind’s to experience this truth in its learning, curriculum and pedagogical practice? Tagore believed that children’s minds are sensitive to the influences of the great world to which they have been born. Their subconscious mind is active, and with it realizing the joy of knowing. This sensitive receptivity of their passive mind helps them, without their feeling of any strain, to master a language, that most complex and difficult instrument of expression, full of ideas that are indefinable and symbols that deal with abstractions; and through their natural gift of guessing they learn the meaning of words which we cannot explain. It may be easy for a child to know what the word ‘water’ means, but how difficult it must be for it to know what idea is associated with the simple word, ‘yesterday’. Yet easily they overcome innumerable such difficulties owing to the extraordinary sensitiveness of their subconscious mind. Their introduction to this great world of reality is easy, effortless and joyful because of this.

Our school system aims in the opposite direction with its examination oriented, mechanically regimented, and rote memorization driven classroom processes that are tightly framed with a time table and a school calendar. In co-travelling with Tagore’s writings on education one gains awareness of the innermost truth of how school does not allow students to experience the completeness of life but is merely an arrangement to provide lessons in so called subjects. He believes that nature by itself is the greatest teacher of young children and aches that his words cited below become the inner vision of school planners and administrators.

I believe that children should be surrounded with the things of nature which have their educational value. Their mind should be allowed to stumble on and be surprised at everything that happens in life today. The new tomorrow will stimulate their attention with new facts of life. But what happens in a school is, that every day at the same hour, the same book is brought and poured out for him. His attention is never hit by chance surprises from nature. (2).

The necessity of looking at young students as natural actors of their experience never comes out in school practices notwithstanding that,

In our childhood we imbibe our lessons with the aid of our whole body and mind, with all the senses fully active and eager. When we are sent to school, the doors of natural information are closed to us; our eyes see the letters, our ears hear the abstract lessons, not the perpetual stream of ideas which form the heart of nature, because the teachers in their wisdom think that these bring distraction, that they have no great purpose behind them (2).

It is in the inward walk with Tagore that a young student realizes how limited our school education with its narrow specialization of information-gathering solely through the intellect is. The pandemic campus closure further highlights how institutional arrangements for nature to educate students are absent in course curriculums. He urges that the human mind should be saturated with the idea that he is born in a natural world and is one with it. The confinement within the walls of urban homes and the farcical online information based lessons represent no such harmony with the world. It is an education that is as far away as could be from his vision of education as that which does not merely give us information but makes our life in harmony with all existence.

‘I am large. I contain multitudes.’ Synthesis of ideas

Avijit Pathak is a contemporary educationist unlike both Krishnamurti and Tagore. He is different also since he is a professional sociologist and a formal academician. Yet in his theorization of education he also rejects the prevailing school system for the same reasons as Krishnamurti and Tagore: ambivalence to the deeper meaning and significance of life and its distortion into artificial hierarchies that breed alienation, competition and discontent among the young. The much ado of the examination regime on school systems, the clearly-defined stratification between the various streams of study based on hegemony of particular disciplines like science and technology, and linking of academic achievement with market prospects; are some of the elements of the school system that Pathak critiques. He considers examinations as training in regimentation, memorizing and mindless drilling aimed at evolving a ruthless efficiency in answering a given number of questions with speed. He writes,

Exams…promote a cult of quantification which devalues a child’s specificity, quantitative distinctness and uniqueness. Exams are supposedly ‘neutral’ having a uniform/ universal scale through which a child is evaluated, quantifies and hierarchized. But then, it should not be forgotten that each child has her own distinctive experience of learning. One may be inclined to abstract theorization; another may feel comfortable with concrete life-experiences. (3).

He further argues,

One may have a high degree of oral articulation; another may have a good writing skill. One may be oriented to mathematical reasoning, and another to poetic sensibility. All these differences are, however, eliminated, and at the day of judgment- the day of final examination at the end of the year- a set of questions manufactured by anonymous experts is distributed amongst all, and children, irrespective of their specificities and socio-cultural locations, are ranked through a uniform scale. (3).

His educational philosophy advocates junking an exam-centric approach to education which reinforces the duality of success and failure in favor of something that not only truly challenges children but also is life-affirming. He synthesizes ideas about the human condition and the role of education in it. It is as if he translates Walt Whitman’s sentences, “I am large. I contain multitudes” into a vision of education. Elaborating this he writes,

Exam-centric education breeds fear, envy and superiority/ inferiority complex. In a way, it legitimizes hyper-competitiveness as a way of life; it is inherently against the spirit of reciprocity, symmetry and cooperation. Hence, its ‘successful’ products-the bunch of ‘toppers’ and ‘gold medalists’- tend to be egoistic. The art of relatednessness, humility, the ethos of sharing, and trust in the innate possibility uniqueness of every human soul-we do not allow our children to develop these qualities. (4).

According to Pathak education involves a moral quest which is possible only by celebrating the vocation of teaching, a celebration that recalls what is forgotten within. He imagines education beyond the parameters of a schooled society. For education to have meaning it is essential that it connects the self with knowledge of the world as also with the knowledge that is presented as a school curriculum. This participation of the self in the process of knowing is not different from what Krishnamurti calls self-awareness and regards as the essence of education. He himself walks with Tagore in quest of an education in which the ultimate truth is not in the intellect or material possessions but illumination of the mind (5). He probes into the dynamics of formal education not only as a teacher with sustained engagement with critical pedagogy and life-affirming education, or even as a sociologist undertaking a penetrating socio-philosophical and pedagogic inquiry into the dynamics of discipline, freedom, creativity, and education but also in the spirit of a wanderer (6). Motivated by the belief that discipline is intrinsic, he further critiques the repeated drills, passivity, destruction of imagination, and fear evoking the nature of practicing discipline in our education system.

Walking an inward lane while supporting his stance with personal and general instances; his ideas can generate metanoia. For instance, he points out how cricket is hardly appreciated for being the game it is, instead, it is reduced to a war zone with negative emotions completely taking over if the ‘enemy’ nations play better. The rise in normalcy thereafter witnesses mob violence, herd mentality, aggression, helplessness before markets, and media-directed needs. In the anecdotes shared by him of a PCM (physics, chemistry, mathematics) student and students from Kota, their parents, and the surroundings, Many of the readers can see their past at those vulnerable ends, confiding and rebelling those homogenous boundaries, leading to the euphoria of success and the stigma of failure. Such an education runs the risk of turning young students into narcissistic conquerors rather than seekers. (7).

Any seeker can rediscover herself as a student and as a teacher in walking with the three educationists. In this context it is noteworthy that Avijit Pathak uses ‘she/her’, while Tagore and Krishnamurti use ‘him/his’ as general pronouns. This poem presented by the principal of an American high school to new teachers in his school as they started their first day of the new school year resonates as an aspiration for the future of school education.

Dear Teacher

I am a survivor of a concentration camp. My eyes saw what no man should witness:

Gas chambers built by learned engineers.

Children poisoned by educated physicians.

Infants killed by trained nurses.

Women and babies shot and burned by high school and college graduates.

So, I am suspicious of education.

My request is: Help your students become human. Your efforts must never produce learned monsters, skilled psychopaths, educated Eichmanns.

Reading, writing, and arithmetic are important only if they serve to make our children more human. (7).

References

- Krishnamurti, Jiddu. 2014. Education and the Significance of Life. Chennai: KFI.

- Tagore, Rabindranath. 1996. “My School.” In The English Writings of Rabindranath Tagore, edited by Sahitya Academy. Vol. 2. N.p.: Sahitya Academy

- Pathak, Avijit. 2009. Education and Moral Quest. New Delhi: Aakar Books.

- Pathak, Avijit. 2021. ‘Let’s go out of syllabus’, The Indian Express, April 28 2021.

- Pathak, Avijit. 2021. ‘In troubled times, walk with the poet’, The Indian Express, May 9, 2018.

- Pathak, Avijit. 2020. “Rethinking the practice of education.” In Culture, Politics and the Aesthetics of living, New Delhi: Aakar Books.

- Ginott, Haim. 1972. ‘Teacher and Child’ In Congruent Communications New York : MacMillan also cited in Mitchell, J. ‘Children of the Holocaust’, The English Journal , Oct., 1980, Vol. 69, No. 7 (Oct., 1980), pp. 14-18 accessed at https://www.jstor.org/stable/817398 on June 29, 2021.

- Pathak, Avijit. 2021. ‘From narcissistic conquerors to seekers’, The Indian Express, July 3, 2021.

The article is insightful and compells the reader to rethink and reflect on many daily life practices of present education system. It is very well spotlighting aspects related to mechanization and routinization of otherwise ought to be the most curious and natural activity for the children – learning. The narrative is woven around two well established educational theories giving the reader a substantial thought to ponder upon further connecting it to the intriguing speaker of present day- Dr pathak.

Amazing read !!

Congratulations to Dr Raina and Samriddhi for the well written piece of work.

I can’t describe in words the richness of this article. Highly detailed and insightful analysis. Thank you for providing with this beautiful article.

Enjoyed going through this article very much. Beautifully penned down.