The Reluctant God

Revanth is somebody who is either a hermit who has made his hostel room his haven or a wanderlust who has hit the road. When he is not reading books, about books, or talking about them he is engrossed in classic Telugu films.

Preface

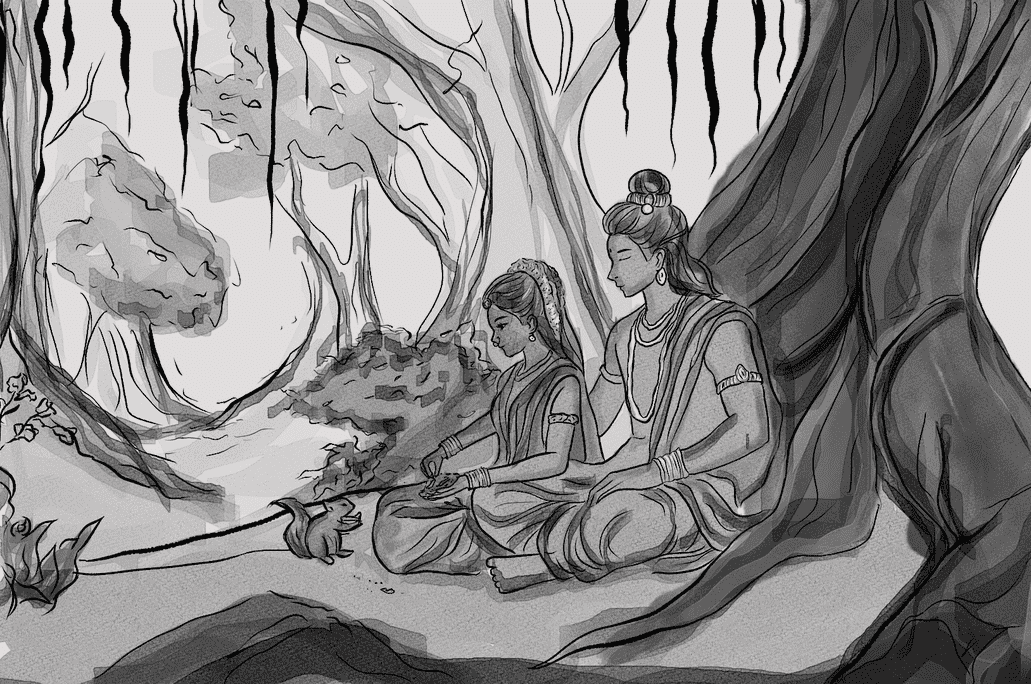

For every person, their Ramayana. In every Ramayana, its own Rama. There are hence, to me, more than AK Ramanujan’s “Three Hundred Ramayanas” and there are millions of Ramas. Likewise my Rama too. The zeitgeist of now is one where one Rama has steamrolled over these millions and mine too. In the immediate aftermath of the consecration of Rama Lalla in Ayodhya on January 22, and in view of what is destined to be a catastrophic fallout in coming years for India’s democracy, political health, culture, and even Hindu religion, this short story lets my Rama speak. He is seated in an unnamed forest grove with his wife Sita – an air that he is most comfortable in. In the conversation between the two and the ensuing breezes of their thoughts, I wonder how the present moment of frenzied excitement over a gigantic construction of a temple and humiliation of a faith can amount to the humility and thoughtfulness by the many Ramayanas. The theme of the manifold (Rama)yanas becomes the method of this story. In so many ways Rama has been made to reckon with the greyness of his life – like in Bhavabhuti’s play Uttararamacharitam. In still others his simple living in the forest is extolled and often in contrast to the splendour of palatial Ayodhya – not least in Valmiki himself, but also as I depict here, Kamban’s Tamil Iramavataram. I invoke several poets for their unflinching conviction that love of Rama was only to be felt in the acts of feelings of the humble: Tulsidas in Ramacharitmanas and in this short story, the Telugu songwriters Kancharla Gopanna and Tyagayya. I invoke also moments in the Ramayana where Rama has or in my view ought to meditate on the complexity of his life – the killing of Vali for Sugriva, the repeated ordeals Sita is made to undergo, and the killing of Shambuka for the sake of maintaining the Varna order. Finally, moderns Kaifi Azmsi and Gandhi make their entrances and exits in my short story. The point of this story is not that the answer to faith is faith; instead, as DR Nagaraj masterfully argued in the context of Dalit politics, the reclamation or even reimagination of narrative and culture is imperative for the building of a movement. I do not claim that in any way this is a first, but it is certainly a plea to and an attempt at precisely such an imagination.

“Devi there is an imposition upon me,” Rama said with not a twitch in his visage. From the corner of his eye, just for a moment – even before the moment could feel that rustle – he gazed at the now-large furry squirrel, fattened by all the wild berries and nuts that Sita fed it, as he prepared to part from it. All things that had been wild, meaning all things that Rama resided in were to retreat. There were passionate calls from a new world. “Imposition?” Sita pressed quizzically, “one I am unaware of?”. She continued, “and not imposed upon me!” “Well, that is the odour of the Age, love. Even in the greetings people offered to each other, they dared not to separate us but in this new home that I am set to enter, you shall not be. They say I am to be a five-year old boy, a child in his natal home – a home chained to some mysterious coordinates set by Valmiki.” The squirrel gently perched onto Sita’s fingers, dropping a few grains from its mouth, salivated and all. Sita smirked with wise candour and remarked somewhat unintelligibly, “Separation has been the essence of our love,” as if speaking to the wind; after all as she sat humiliated across the ocean, Rama had said to the wind: blow, touch her and touch me too for therein I shall feel her gentle touch. She was now preparing, already. But that day when Rama revelled being aware that they two breathe the same air, he had before him, Hanuman, the son of the wind. Would he play messenger too? Or would Venkatanatha’s Hamsa do the trick for Sita? Do these beings even listen to the ladies? Will Rama’s new home let even a wisp of these messengers touch her husband? Behind the cloister of silence, as Sita spiralled like Kalachakra, Rama’s nagging cut the loop and asked for attention.

“I will not feel at home there,” he spelled. “Why do you say that, dear?” she asks as if innocent, as if unknowing. “Was it Kamban?” he asks framing his chin with a cupped hand for a bit – “yes, yes it was him – who so well captured our moments at Chitrakuta, the threshold of our long honeymoon in the wilderness.” Sita welcomed a smile – she knew of course where Rama was going, perhaps even better than him. “When I likened the shed slough of snakes quivering on long bamboo branches to the triumphant, haughty flags of Ayodhya, it was not mere consolation, my heart! I relish the wilderness like my soul, like my – let me just say, you! Yes, you. I relish the forest in all its untamed brilliance, its verdant splendour, its charm like I adore you. After all are you not Fortune herself, and a shoot from the earth.”

Sita was amused about how this new invitation may after all be another exile for her husband, who was famously an exile par excellence, a somewhat byname for exile if one will. Kaifi Azmi was correct, she thought: the day the Mughal building was torn down, was indeed their “second exile”. That very moment she had imagined placing the poet’s face on her laps, caressing it – like he was her son. Not too far after all this imagination was from Valmiki’s own words with them in Tulsi. Lauding Rama’s alacrity to tear down webbed leaves to make roof, and trunks of lofty trees to build huts in the rugged jungle, Valmiki could not, on Rama’s request find any one spot for the residence of Rama. After much thought, “ears”, he said – ears of those who heard Rama’s tale with eagerness. Eyes – of those who seek his image, but also hands and legs – of those who will to do good in his name. All of these were also paths of gallivanting around images and names. Valmiki was right, Sita thought to herself when he tried to locate Rama in the minds of those who thought about him. But she wished she could make a correction; he of course would live in the minds of those who thought of the blemishes for Rama thinks of them too, even today. As he sweeps the ground for every night she slept on the stone-bed in the Ashoka orchard, and stitches her fragmented garments for every morning that she changed from bark to bark. Thinking of all this, Sita nearly said – now look where you are headed. But what lover would she be if she pierced into a blister of misery.

Instead, she remarked with glassy widened eyes, “Oh Rama, think about the day you entered Ayodhya from Lanka. Is this not a mere re-enactment of that epochal date?” Rama nodded his head gently, as his long nail scratched the surface of a rock. He stared for a few moments at his dark hand and then like a spark resumed: “Yes indeed I remember that day Sita. Victorious, we were, no doubt but recollect how Bharata arranged a welcome party for us. As much as the people of Kosala were in merry, I was surrounded by something of a different register. We two brothers shed the moss of homelessness, hunger, and misery with the haircuts we got from the royal barbers. Meanwhile, I was guarded by noble beings like Jambavan. What a philosopher he was! Am I anything near him?” Sita inched a little closer to him, her bangles jingling gently as she slid and her garments shuffling subtly. The self-aware smallness of Rama drew Sita’s love without end. “And there is Sugriva. We were comrades in guilt, Sita. We both won our territory and consort back, but we bore the weight of regret. And then Hanuma – what to say of his enthusiasm for marital affection.” Sita’s palm was now on Rama’s; her hand was her own bridge. She desired no oceans to be leapt over. The blue god turned to Sita whose face was affectionately now close to his, and said: “Darling, I must say that on that day, underneath the hard skull and skin of victory were the sweet juices of meditation.” Both Rama and Sita let out pathetic chuckles. “Now see,” said Rama, “I am being ushered in like a prince with unwanted pomp and suffocating dazzle and worse! I am being held by Ego by my hands so I do not lose my way. Where, Sita, is all the sagacity that our tale is written with?” Now almost agitated, Rama wailed, “I denied throughout my life my godhood, no matter who or how many urged. And now, now look! I am now merely nodding to the godhood of a few men.”

Sita shrouded Rama’s back with her arching arm. She placed her chin on his shoulder, looked at his wiry hair and large ears. But then looked through them and into the puddles of his words. Indeed, Rama was right. He had been all along, the god of the meek, the lean, the helpless, the pleading, poor, and always, the protector of the gently patient. Why, it all began with her. She ran her fingers on her thick, long oiled plait – decorated with garlands of marigold and remembered these locks in their disheveled year. Had she not merely waited? What to say of Ahalya, who waited not like, but as a rock. The love that Rama was wrapped in by Shabari made even Sita jealous, and it had always been the love of such souls that had moved Rama. She also remembered the shackled Gopanna as he cried to Rama and Tyagaraja in his pleas to rescue him. They could both not have assumed less about themselves. Sita thought – Rama was right about one other thing. To those that Rama was dear, they could not picture him apart from her. And they could not picture her apart from themselves. She was one of them – they had all been girlfriends and wives who waited for him patiently. And now as they waited, they sent petitions to her. Gopanna nudged Sita, “O Sita, my mother, tell him to rescue me – when the soul of the world, the beloved of Sri has his solace with you…” Tyagayya had not strayed from this supplicatory register but one song, though, she had always been specially pleased by: “You have become a king by grasping the hand of our Janaki!” Yes, how right Rama just had been. A palatial shrine for Rama without her, an oddity. A perversity indeed. She could not also avoid thinking of that lean man who preferred to “walk alone”. His last breath was apparently fizzled out for her husband. Was he not another entle faster? Till such a fast, in service of an “enemy”-state had forced the embarrassingly named “Nose ring-Ram” to rob him of his life.

By now, Rama had slowly freed himself from the clutches of love and exposed himself to the breeze. As if to drag him back to his condition of being bound to her, Sita called out to him. “Then tell me dear, why do they do this? Why are you called into this house?” Promptly he replied, “It’s the popular will they say. This is what the people want.” Sita paused for a moment and in a few small steps, trailed her husband. She let an uncomfortable silence, somewhat uncomfortable even for her, parse the earth. “Is that not what you abide by? You wish to please your people, do you not?” Rama reckoned himself, the himself of that moment fortunate for he had turned away from her – the other side. For now. She was right. A new ruler had put Rama’s political philosophy into practice. What Rama had been taught as the ethic of the Solar Dynasty and what he had sought to emulate, somewhat uncreatively he was now realising, someone had followed like a textbook. Only the king of yore had done it at the expense of living peacefully with his wife, and executing his duty towards her, as her wedded partner. He had forced her into the wilderness, which he had just some time ago spoken of with honeyed lips. Many a night would be spent sleepless fearing if Sita had been ravished by tigers – yet he remained aloof from her. How many times he had had to sit before the guilt of his doing. Why, as Bhavabhuti in whose ink, Rama’s stone-heart had bloomed like flower, made Vasanta say: “Was ill-repute really worse than the misery of suffering away from his wife and spending every waking moment – every moment that is – being anxious for her?”

There was a word of defence still for Rama: no he had not merely put people’s word to the fore. He had not been a populist. It was not enough, in other words, if the lot approved of him; everyone was to be made happy. Not one, that is, was to remain displeased. While he indulged in that thought, his own conscience reminded him that he imposed not displeasure but death in all its severity upon a young man, whom despite being his subject and a like-son to this like-father, he had once slain. Shambuka – that name pinches Rama. He had apparently sworn himself so much to Varna – and the trappings of birth that a man, learned and pious as he may be, born to a Shudra could as much as be a transgression of laws of nature, a cosmic pest, an ethical epidemic. And extinguished, he was – by the hands of Rama. Every time modern Indians sang, “Ram, praised by the heaven-gone Shambuka”, the fiber of irony grasped and strangled like a noose. Rama recounted that he had been praised by a man he had killed; only a devotee could go only as far as to rhetorically and euphemistically say, “heaven-gone” and not kicked by force into that heaven. Rama was a moral jigsaw. He was apparently the hologram of Dharma but pursuing the theory meant being an ever-suffering practitioner of what would only prove later to be ills.

Rama now asked himself: had the guilt that swirled around him even dawned in meagre measures to the millions who were now throwing open, very fiercely, this invitation? Did not his tale beg to be a journey not merely of devotion but one of feeling and thoughtful meditation? Once again Rama looked behind at Sita, still stoic, the keeper of his conscience, and also its most brutal victim. History seemed to hiss at him – with the cries of thousands across his land that had lain their lives for the making of his new home. His housewarming if you will, his consecration was being written with blood. He knew not what precisely to say after having slain demon after demon and occasionally offering the present of death even to his devotee. The jigsaw that he was perhaps had not given him the strength to refuse. His own chequered history seemed to give a nod to war, and his own ethics pleasing even to those who were on the wrong.

The jigsaw had to make strides into the new house. Apparently, it was the prerogative; the imposition that he had begun his protest with. Sita, his victim and wife knew nature well; she was born to it, lived with it, passed through it, and rested finally in it. And the rules of nature that she knew dictated that Rama had to go. The past of Rama meant that in his present, this fresh somewhat sullied palace was to be his unwilling home. And those that knew him so well would have to watch.

The jigsaw made strides, alone. Leaving his world behind, he found a new home.

Featured Image Credits: Navbharat Times