How the Telangana police encounter killed Disha forever

Srinath is the Founding Editor of The ArmChair Journal. Currently at the University of Chicago, he is also an alumnus of IIT Madras, Ashoka University, Rishihood University and Purdue University.

Several years ago, the SP of Warangal headed an operation that killed three men in an encounter. Those men were charged by the police to have poured acid on a lady. A few days ago, the same policeman also headed the encounter, which shot the four accused in rape case of Disha.

Let us now go back to the times when India hit Balakot in Pakistan. This is where the intimacy between politics and truth becomes evident in a perfect manner. When India apparently struck its target, the debate was fierce both on social media and on hard ground. Both the countries held their political positions, as to insult their opponents. India said it hit the targets as planned while displaying ignorance about whether they killed the terrorists, and Pakistan said India hit some trees in Pakistan and raised environmental concerns.

When we do not know the truth and display an urgency to take political positions, we have the flexibility to weave our own stories. The mere reason that truth is not clear means we can recreate the scene in our imaginations, which suit our political beliefs and stay comfortable in our cocoons. Media helps us with all possible facts to facilitate imaginations. We also had independent researchers who used satellite-enabled sophisticated technologies like the Google Maps to see how pictures of the target changed before and after the attack, as apparent from the carefully extracted screenshots- so as to prove that something was surely demolished.

One’s political identity is matured when one is able to create such stories in more such situations and answer the questions asked by common sense. We are now experts at holding our political positions without any skepticism. Some of us believed a lot of terrorists got killed when the Balakot attacks happened. The position that we take when the truth is blurred is a political position. Our political values make us create stories that match them. One should only wait for a situation where the truth is blurred to identify anyone’s political inclination.

As such, the performance of politics sees truth as a distraction. In other words, politics cannot exist where truth exists. Politics become irrelevant in situations of truth. If everything is clear, where is the scope for discussion, and thereby politics? If we look at it differently, the pursuit of politics itself is to understand some truth so that we can lead the lives that we deserve. That’s why we allow politics in good faith, after all. This particular feature of politics is essential in democratic affairs, and this also makes consensus easier.

However, we cannot survive in politics if we become irrelevant. Hence, more is the situation where the truth is not known; more is the vibrancy of democracy. Political parties can thrive by feeding their version of stories to the partisan audience. Pratap Bhanu Mehta countered the arguments that we have entered a post-truth era, by saying, politics has always been post-truth. What it means is that the mere reason why politics was possible is also the evidence that the truth was not clear. If politics has always been there, that means truth in such a situation has never been clear. Or, truth kills politics. Conversely, we can observe that politics can kill truth if there is an incentive in it.

Hence, to survive in politics means to look for situations where the truth is not clear. In fact, one’s survival or self-preservation is also an incentive for one to destroy more and more truth.

When the victim Disha was raped and murdered in the outskirts of Hyderabad, the victim’s dead body was also burnt. This is nothing but an effort to destroy any possibility of evidence of rape, and the consequences of it. This is an effort to blur the truth so that the perpetrators can weave stories and explain their positions. One of the accused, Arif, told his parents after reaching home that he killed a woman on a scooty when he was crossing the road in his lorry.

In this process, like several Indians could argue that our loyalty to the nation was under question if we did not believe that the IAF hit the target, Arif also offered a story so that those who had faith in him would find truth in it.

This was the first act of politics in the incident. The accused narrated stories to their parents after reaching home so as to gain their sympathy or mislead them, if at all.

These politics failed as soon as the truth was being established through techniques like the post-mortem examination. Once the truth was out in the media, the reaction was outrageous. Arif’s politics was not possible anymore. His parents wanted to disown him too. People surrounded the police station in agony to kill the four accused at Shadnagar.

Students protested, and people called for the death penalty to be imposed. The parents of the accused also expressed their opinions to kill their son at the same site where the victim was raped. However, laws existed to deal with this situation, and ‘due process’ was also expected to be followed. Fast track courts were expected to deliver justice soon. The chief minister assured the same.

People were impatient, outrageous, and wanted to execute the rapists. To lynch them publicly was also an option to be considered. Many supported it, ‘educated’ or not. However, no one popularly called for an encounter, though everyone wanted to lynch.

During all this, the protests were legitimate. There were a lot of opinions calling for harsher punishments for rapists with quicker justice delivery. The anger was justified. The protests appeared to care about women.

All through, women were seen as the victims, and we wanted reforms all across to improve justice delivery and improvement in social structures. We wanted children to be educated well so that they do not commit rapes or any form of sexual harassment, and we also wanted parents to teach better moralities to their children. We reminded ourselves of the ‘Indian’ culture, which always respected women in various forms. We even wondered why she did not call the police by dialing a simple ‘100’.

The act of rape was seen as if only the four individuals were responsible as they were the perpetrators of rape. The victim, also seen as an individual, should have resorted to safety measures to protect herself from these perpetrators. Even when the state was doing everything, she was not smart enough to make use of them. Isn’t it?

Though we can immediately attribute the cause of rape to those four, we can infer from the last call Disha made, that the rape had a context in it. In her last call (translated into English here), when Disha was suggested to go to the toll gate, she was afraid that everyone who would pass by the gate, would stare at her. The ‘everyone’ she was referring to, was nothing but men. Disha’s sister even confronted Disha questioning her why she had left so late at night in the first place? Even this, she tried to answer, saying she was not able to find time in her routine. Disha, too, was fighting with herself to make sure it was not her fault.

It is not just that four men raped her. The whole of patriarchy and restrictions on women made the context possible, such that Disha doubted her act of coming out at such a time of night as wrong. Disha was also afraid she would be objectified as usual if she stood at the Tollgate. She was searching for a physical and metaphysical space to be free from those four ‘ghosts.’ She wanted to negotiate a position to justify herself, even at the cost of avoiding society. Rapists merely formed the extended family of patriarchy, which could be taken support from, anytime.

The gist of the protests in this situation was that several bad men raped a weak, vulnerable, divine woman; and good men must deliver justice. However, the way justice was delivered makes us feel it was sheer power at play. If it was so, whose power was it?

Good men had an obligation on them to prove their goodness, after all, which good man did not worry about the safety of women and women empowerment? Several good men could easily feel they must eliminate the bad men within them to preserve their goodness.

Who knows? Whether the good men from the upper classes were hurt when the lower-class men raped their daughters. Who knows whether it was an act of revenge by the good men from the upper classes to show the loafers of lower classes their place saying the law does not come in their way, or whether the accused tried to flee.

Who delivered justice, and by whom? Who secured it? Was this a justice delivered to the upper-class male ego that was hurt? Was it the justice delivered by patriarchy in its own masculine way? Did the government succumb to populism, and was the encounter just like another freebie to comfort the masses? Who would execute the system which had its stake in it?

Since everyone celebrated it alike, was it a justice delivered by society as a whole? Why would women celebrate at all if it was patriarchal justice delivered? After all, why did Disha’s sister confront her in the last call, like every man, about why she left so late at night?

It was a kind of justice delivered by men across all times- a powerful masculine one, which in turn, they used to keep women too oppressed- which created the very context for the rape. The state was there to expose the politics of Arif, who is there to expose the politics of state?

The police encounter was the second act of politics in the incident. In a single stroke, it killed all truth, which could pose these questions. Unintentionally, it was an effort that tried to avoid the consequences of accepting the truth of patriarchy, like the story created by Arif towards self-preservation. It was patriarchy’s attempt to preserve itself. The police behaved just like the Arif. The male-like government failed the women once more. The matter is finished.

Disha was still alive in the protests as a hope for change. The encounter killed Disha again, and this time forever. We need to wait for true justice to happen until every ‘man’ within us is held in the trial. Till then, we can weave our stories to justify our political positions.

Who knows? The police encounter eleven years ago was responsible for today’s rape, too, as long as it delivered justice the male way and preserved patriarchy.

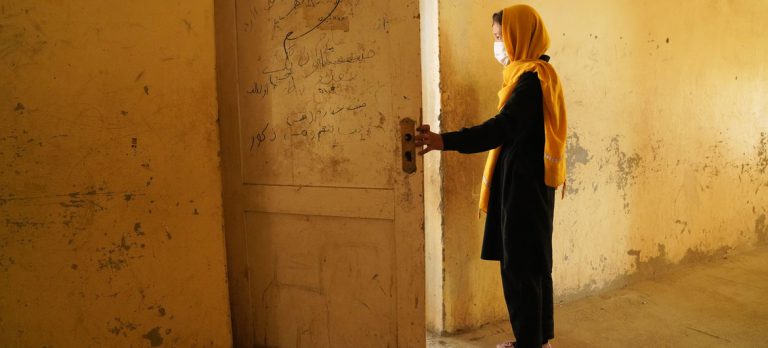

Featured Image Credits: Hindustan Times

I dont quite understand what you mean about the legitimacy of what her sister said. Are you saying that one should not feel concern for the safety of a woman going out late at night or even otherwise? I understand your idea: women should be able to go out anywhere at any time of day and night, and if they cannot or if they have to confine themselves out of danger, then that is the sign of patriarchal society. Ok, but there is something absolutely ridiculous in this idealism. There is danger out there, pining for and taking a lofty position against it misses the point completely. Tell me personally. Suppose a woman friend of yours gets stuck in a sticky situation. Are you not going to judge the purpose of going out? And, if not in the real case but this imagined one you feel she need not have, is your concern or question illegitimate? I dont think so. This infinite purity of intention on your part runs against genuine concern. At a personal level, it is more than proper to ask a close one.

Sure, it is patriarchy, but something is missing if you make it a general concept. It is not the same patriarchy as traditional patriarchy, and analysing it requires more than a general denunciation of it. Making rape solely a women’s problem also is an underestimation. There is more to it. Why do you want to keep men out of the struggle against sexual violence?

And what do you mean when you say attention was diverted from the rape itself? Attention, however flawed, was on justice. Should it not be so? I think it should be at practical level, instead of going on and on piously about the perils of women and expressing anger at helplessness. Justice had to be extra-judicial because Law formulated for traditional patriarchal society is not keeping up with the changed context. I read it as a symptom of this, and also an an attempt to shift ground, almost as desperation. Recognition of this element, rather than introducing class-caste questions and lamenting the deflection from ‘real’ topic, is for me the most crucial lesson from this case.

Don’t underestimate the support the killings received from ordinary people.

Srinath,

Yes, such politics could be undesirable for you. But you have to take a more refined view of politics as the conflict between different versions of ‘truth’ rather than retain truth for yourself and deny it to others. And by all means, it will require a far nuanced effort to analyse why what are lies according to you is passing as the most dominant version of the truth today. You are immature in calling it undesirable and leaving it there. There is no simple truth that we can all reach to if only we clear away the layers of lies. What is ‘post truth politics’? It is when traditional legitimacy of hierarchy can no longer function and politics turns from warfare and position maneouvering to a fight for domination in representational space. Don’t underestimate the fracture in ‘truth’ as undesirable. That IS politics today.

Also, I’m interested in how according to you ‘justice delivered by society as a whole’ should have looked in this case? If not like this, then what exactly should have happened?

Also, I am not aware of Arif’s confession to his parents. Anyway, I dont understand how you found politics there. If he did give it a spin and tell them, then it only shows that he was disturbed and guilt got the better of him, considering it was before he was arrested and had no reason to tell them beforehand.

I would like to first bring to your attention that I made a few edits to the article, which were not reflected due to technical issues. The edited part now shows this:

“The gist of the protests in this situation was that several bad men raped a weak, vulnerable, divine woman; and good men must deliver justice. However, the way justice was delivered makes us feel it was sheer power at play. If it was so, whose power was it?

Good men had an obligation on them to prove their goodness, after all, which good man did not worry about the safety of women and women empowerment? Several good men could easily feel they must eliminate the bad men within them to preserve their goodness.”

Coming back to your comment:

Thanks Rajdeep, for sharing the reference of Carl Schmitt. I would surely find time to go through.

My attempt was to show the similarity between the way Arif played politics, and patriarchy played politics, both towards self-preservation. As such, I do not aspire for a position where politics is undesirable, or that the only aim of politics is to kill truth. I was highlighting the possibility that politics could kill truth for its self-preservation. In this context, the encounter appeared to be a sheer display of power beyond normal law. If it was so, and since the evidence was not possible, it created a ground for political positions to interpret the action of the police- or the intention behind power.

One such interpretation is the possibility of class differences propelling it. By definition, it can’t be truth. I have not superimposed class difference on the rape as such, but only on the events surrounding it. Rather than taking a position sympathizing with the lower classes, my aim was to highlight the possibility of the question itself and nothing more. The question gains its legitimacy from the day of encounter, and prior to it, it would have sounded stupid.

In fact, what is closer to my position is that there was no focus on rape at all in the way events unfolded. The encounter took the context away from rape, and it was just good men versus bad men, while superimposing bad men and the lower classes. As it happened, this was not an issue about women, or their oppression at all. At max, women were sidelined.

Coming back to your remark, “you will be stuck with politics as obliteration of truth,” I do not think this is closer to my inclinations. I can just admit that politics can obliterate truth for their own survival- and to the extent it is possible, such particular politics could be undesirable.

On this: “Also, this case leaped up from its particularity and became a universal container of injustice in society.”

I agree. However, as what followed: I do not think this was a justice delivered by the society as a whole- though almost everyone celebrated it popularly. To say it is so, is to see the question by Disha’s sister asking her why she had gone out at such a time of night- as legitimate.

What do you think?

Take time to read carl scmitt’s concept of the political and try to understand the Friend-Enemy distinction that is at the base of politics. Otherwise, with your ‘skepticism’, you will be stuck with politics as obliteration of truth. There is no independent standing of facts, there is always an interpretation to present the facts, and the conflicting presentations IS politics. There is no single identity of politics as obliteration of truth, and its survival does not depend solely on creating untruth. This will only lead you to a notion of politics as something undesirable, getting in the way of something better. This is completely wrong, and for this reason your analysis suffers from a vague notion of ‘us’ the thoughtful people against the rapidity of faulty interpretations stemming from partisanship. This, I would suggest, is obliteration of politics. Do you really want to hold on to such a position?

Also, this case leaped up from its particularity and became a universal container of injustice in society. It may have its faults, but parroting Rule of Law and ‘this is a complex situation’ is more of an avoidance of what is quite clear. When Law was harsh, popular sentiment tended towards humanist sympathy, but now that Law is humanitarian, popular sentiment is naturally going to turn hostile. Should rapists be killed? Should there be different punishments according to social background of rapists?There may be a class dimension to rape, but to superimpose that dimension on the case itself is wrong approach. This overflow of sympathy for the disadvantaged has missed its target, or is rather too casually used to deflect from the basic problem of the rape. If you want to analyse currently existing patriarchy, do a serious theoretical analysis and do not use this case and that case to forward vague ideas that only create more resentment towards intellectuals.