Grave of the Fireflies: An anti-Hollywood war drama

[Spoilers]

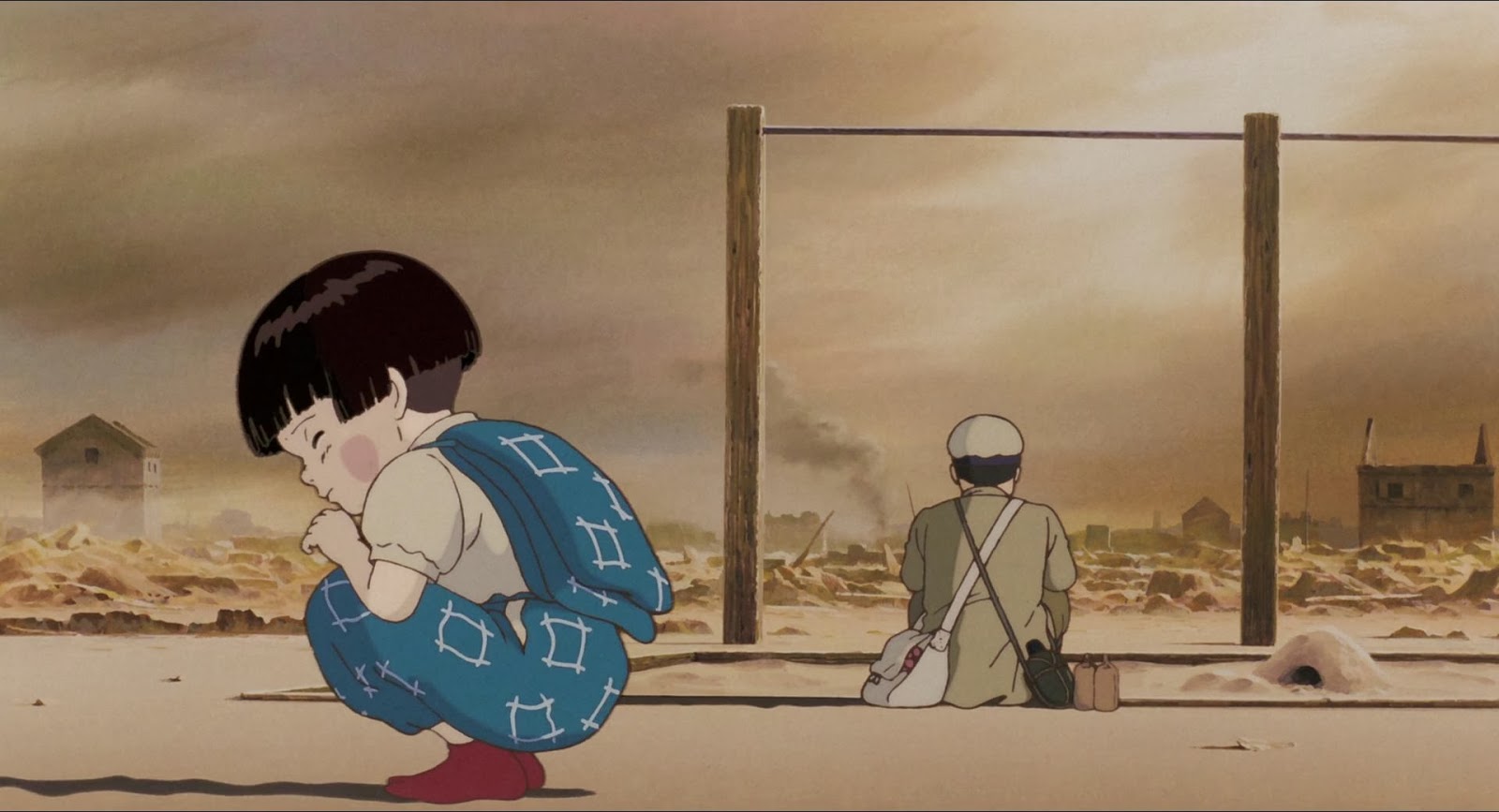

What can be more painful than seeing two orphans starved to death in an abandoned area- a perfectly fitting gesture, as I find it, and I’m sure most of you will agree once you see the movie, for one of the greatest anti-war films humankind has ever produced. Even the great American critic Roger Ebert was moved just about to tears after seeing this rare piece of gem. “Grave of the Fireflies is an emotional experience,” he writes, “so powerful that it forces a rethinking of animation.” Another US-based film critic Ernest Rister called it “the most profoundly human animated film ever.”

When it comes to dealing with a grim subject such as World War II and its negative impact on the innocent lives of the individuals living in that time, I have to admit that very few movies stand out as being as compelling as ‘Grave of the Fireflies’ with its simple and heartbreaking story of a brother and sister duo in 1945 Kobe, Japan. No matter how many times I watch the film, I still look at it with nothing but awe. The fact that the movie was released in 1988 makes it all the more important, with Studio Ghibli still being in its infancy.

A few years back, a somewhat similar film called Barefoot Gen (1983) was released, which quite literally showed the graphic images of people being turned into ashes as a result of nuclear bombing on the morning of August 6, 1945. These two and some other movies, for instance, ‘Who’s Left Behind’ (1991), were made, perhaps unconsciously, having a semblance of a near campaign that denigrated Japanese government’s war policies over the years. Isao Takahata, the director of Grave of Fireflies, is a survivor of the U.S. air raid as a child at his hometown during the second world war and has devoted his life to making realistic films, a characteristic that viewers hardly associate with animation. Takahata’s longtime partner Hayao Miyazaki, who is perhaps better known outside Japan, helped build the Studio Ghibli, where they both worked for years and gave marvelous results. Although Japan has more than just Studio Ghibli to offer. But for some selfish reasons, my focus here will be on Takahata and his magnum opus Grave of the Fireflies.

Now I know I can throw around some names here that belong to war genre. As it so happens, they are the Hollywood’s biggest hits, films like Schindler’s List, Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, Platoon, Paths of Glory, Saving Private Ryan, Full Metal Jacket- despite some of them being among my personal favorites, have failed to hit me on an emotional level. Hollywood often has a habit of taking such opportunities to glamorize the heroic tales of the competing nations. One can never call these stories heartfelt, with perhaps the only exception of Schindler’s List. Hollywood’s obsession with showcasing the victimization of soldiers alone is old and, if not far-fetched, then certainly far more received. The lives of the individuals or the public who suffered for no reason at all is something that Hollywood has problem addressing.

With Grave of the Fireflies, the voices of those very individuals who had probably no say in the war, come under the scanner to let the world hear a different story than to what people have become accustomed to hearing for so long. What makes this movie so great is its depiction of the murder of innocence, beautifully portrayed in appearance and the circumstances of economic and social injustice, by the two main characters Seita and Setsuko. The film is narrowly based on a short story of the same name by Akiyuki Nosaka, written in 1967. Though critics have often referred to it as an anti-war film, Takahata was skeptical of such claims insisting that the movie is only trying to convey an image of a failed life of a brother and a sister living in isolation. But since the film takes the context of the war, it’s hard to believe so. Moreover, Takahata and many other directors who witnessed the horrors of the war in one way or another, have always been critical of their administration, which led the country in a gruesome war against America.

The movie opens with Seita, who is also the narrator in the story, declaring himself to be dead (someone rightly said ‘Beginning is the end,’ I don’t know if Takahata intended this pun, but I wish he did). His freckled and fragile body lies on the railway station. For the convenience of the audience and also for the aptness of the title, Sieta and Setsuko are almost resurrected to take us through the poignant conditions that brought them to their disproportionate ending. We witness two sets of brothers and sisters. One is the narrator from an oasis of the afterlife and the other from a remote past and whose story concerns the plot of the film.

As the story shifts into its flashback gear, we are introduced to all the important characters of the story, Seita, and Setsuko. They are just preparing to leave their beloved home, as is their mother, to get to the shelter to be safe from the intermittent air raids. Soon we hear about the father too who, as it turns out, is already employed in the warfighting with the Enemy. The father’s whereabouts remain mysterious throughout the film, and whatever little is shown of him is only through Seita recalling his father’s memory. At a time like this, the father’s absence already makes the audience sympathize with the characters.

An unnamed lady soon tells Seita that his mother is fatally wounded in the same attack that he and his sister had managed to survive. Her unrecognizable body is dumped in a grave by the school. When Setsuko asks where her mother is, her brother tells her that their mother has been hurt, but she will be fine, and when it gets safer, they will go to meet her. From this point on, the movie never deviates from its treatment of the subject matter; in other words, it just keeps getting worse for our protagonists right till the end.

The two set out to stay at their aunt’s house; the only family left for them. Initially, the aunt is happy to let them stay with her family, but as time passes, she starts to taunt them for just one reason: they are not contributing to their country in any way while the rest of the family is doing something or the other. The vicious aunt does not care what age group they belong to, especially Setsuko, who is just four. Seita even writes to his father, but his letters are never returned. Ultimately both leave the aunt’s house to get settled in a place devoid of any human contact, a place where they couldn’t last for more than few weeks before Setsuko slowly succumbs to death because of malnutrition, as the doctor says in one scene “All this child needs is food.” Then within a matter of days, our narrator too endures a similar fate.

Discussions over the title of the film mostly take the stance that every single member of this family is kind of a firefly because like fireflies they all act as a light for one another when they have nothing else to rely on and just like fireflies all die so soon, the reference to which is made by Setsuko around halfway in the film when she tells Seita that she knows that her mother is in the grave. Then she turns to ask Seita, who still can’t find words to utter, “Why do fireflies have to die so soon?”. There could be countless other interpretations, depending on which incidents you have in mind, but it’s the one that sticks the most.

So that’s pretty much the gist of the film, and you may have noticed it has got a depressing ring to it. As I watched this animated feature (which by the way is an exciting story in itself because I never watched anime before, never thought they could unpack such a gripping narrative), I was immediately drawn to the story, curious at every minute what is going to happen as the story progresses. Something in the manner of its presentation, the tiny little details of everyday life that the director emphasizes on and how cleverly in just a few shots we also get to see the gory nature of war as the film’s backdrop; all of that adds to giving this anime a fine touch of reality. There were times when I wished that certain bad things should not befall on these two, but usually, the very same thing occurred moments later. Like in that final scene where I hoped that watermelon might save her from dying but it couldn’t. Instead, the narrator tells us, ” She never woke up,” and I felt a heaviness in my heart as I heard those words.

There have been many attempts to remake this film involving real people in it. Twice, once in 2005 and again in 2008, this project was brought to life. But neither of the two could match the quality of the original work. A consensus, apart from varied formative analyses constituted by the experts, is that some things can never be repeated, and it’s not a wrong belief either. If you check with any other great classics, were they recreated and received in the same breath as did the original? I would have to say hardly.

On the surface, this film is about survival, but when you look deeper, it says more. The film is a lesson in itself about the outcomes of the war and so much more. I can go on writing about it and still be not satisfied with myself. If you want to make sense of what I’ve been saying, I recommend that you check this film. I would be least surprised if you don’t want to go through it again once you are done watching, even though you absolutely adore the film.

Featured Image Credits: Critic after dark

Loved this movie……recommend some more