Feasibility of virtual education in India

A pandemic-induced paradigm shift is visible in India’s pedagogical system. India and the world at large have embarked on opening up the education sector, envisaging a transition from offline to a technology-driven online teaching-learning process. According to UNESCO, the education of 1.26 billion children or 70 percent of children in the world got interrupted.

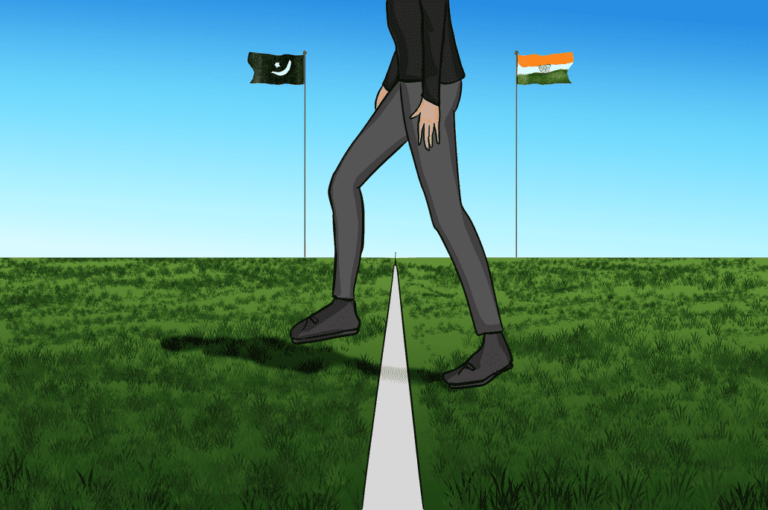

On March 16, 2020, the Indian Central government announced a nationwide shut down of schools and colleges to contain the global pandemic. Indefinite hiatus in the learning process is a blow to it (41 percent of India’s population are from the less than 18 age category), and policymakers and experts are left with the only option to adopt – a virtual model during the unabated penetration of a lethal pestilence. The breakneck spread of COVID19 since its outbreak in January is making the ‘old normal’ a distant dream to fetch. Traditional educational practice characterized by protracted examination is also susceptible to change. India’s education sector is on the verge of an overall structural change, which was an age-old demand from various stakeholders (criticized for following an examination system and not a holistic education system). Technology-driven pedagogy was already on the policymaker’s table and not just a pandemic induced shift. In the 11th five-year plan, the National Mission on Education cited the vitality of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) in education. But egalitarians suspect India’s mettle to craft an ‘inclusive online platform.’ Multiple obstacles lurk in the system making online education a discriminatory exercise. There exists an incongruity between the Indian system and virtual education as a viable option.

Fairness of paradigm shift-a litmus test:

Fairness is integral to any democratic establishment. A litmus test to gauge the fairness of paradigm shift is inevitable to confirm its feasibility. Unhindered access to the internet is the requisite technological input to facilitate the flawless implementation of the online teaching-learning process. But facts and figures demonstrate profound inequality in terms of internet accessibility in India. To cite the data of the National Sample Survey as a part of the survey on education (2017), only 24 percent of India’s households have access to the internet. As per the Ministry of Statistics’ Household Social Consumption on Education in India’ report (2017-2018), for 14.9 percent of rural households, the internet is an accessible commodity compared to 42 percent of urban households. The polarization of India into urban and rural is evident. Urban citizen’s technological prerogatives exacerbate the rural-urban digital divide. Rural laggardness fueled by state inaction to ameliorate the internet outreach in the region deprives the majority of citizens’ right to education’ in a pandemic hit scenario. Gender inequality is patent in the sphere of internet connectivity. The same report of the Ministry of Statistics shows a wide gap in the women-men internet accessibility ratio. While 67 percent of men have access to the internet, only 33 percent of women, which is less than the halfway mark of the opposite gender, enjoy the privilege of internet connectivity. In rural areas, the gap is alarming, with a ratio of 28 (women) to 72 (men). General rural opinion trivializing education as regressive input for women would aggravate the gender gap during pandemic (the majority of the family would expedite the marriage of young girls living in rural India).

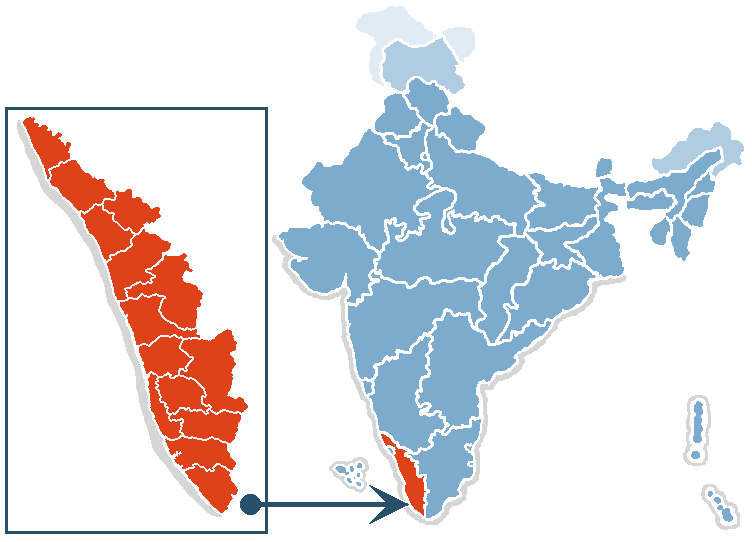

State and region-wise asymmetry in terms of internet connectivity are also apprehensive. Metropolises like Delhi and Mumbai have 2-3 crore connectivity. Unlike the metropolises, the hilly areas of North East India have only 4.3 lakh connectivity. There is a severe imbalance in state wise connectivity data. In the state of Kerala, 51 percent of rural households have accessibility, but only 23 percent enjoy connectivity at home. Among 30 percent of the connected rural households in the state of Andhra Pradesh, only 2 percent are likely to have access at home. Coming to the states of West Bengal and Bihar, the figures are shocking as only 7 percent and 8 percent have access to the internet. Since August 5, 2019, the divided territory of Jammu Kashmir is deprived of internet connectivity. Internet shutdown has caused a dangerous learning gap, and the education sector is on the brink of total debilitation. Though in ‘Anuradha Basin v/s Union of India case, the apex court ordered the restoration of the internet, the government laxity ensured 2G internet only in exclusive zones. The legal battle for internet connectivity for Kashmir is going on (foundation for media professionals filed a petition claiming that it had been eight months since the web was restricted in J&K, and now the combination of lockdown and pandemic had made internet dispossession even more unconscionable) with minuscule hope. Explicit exposition of state-region wise imbalance vis a vis to internet connection is a setback to the coveted project of ‘inclusive and equitable virtual pedagogy model.’

Access to gadgets is equally vital to successfully carry out online education. Chhattisgarh government has launched the ‘padhai tuhar dwar’ (education at your doorstep) portal to unravel the learning crisis created by the pandemic.” We have no smartphone or computers at home. So, I used our neighbors’ phone to register on the portal”, Dolly, a tenth class student in a government school in the state’s Raigarh district said. A teacher hailing from Chhattisgarh’s Jashpur district betokens the difficult nature of the portal’s workability by saying: “Class teachers have to make sure that every student in their class is registered on the portal. But most students either do not have access to a smartphone or have poor connectivity. We could not even reach a lot of students on their registered numbers.”

Being the chief driving force of the teaching-learning process, teachers’ accessibility to necessary mediums of communication is also a matter of concern. According to the Centre for Research, Innovation and Action Research, “90 percent of women teachers have access to smartphones, but only some 40 percent have access to laptops.” Broadcast based learning is another facet of virtual education. Classes streaming through the pan Indian e vidya program (classes for I to XII is available in 12 DTH channels), and Kite Victors in Kerala are perfect examples of broadcast-oriented learning platforms. Unequal distribution of electricity (only 47 percent have electricity accessibility or more than 12 hours) and unavailability of television for all makes this a futile exercise. India’s higher education is also in limbo. IIT developed the Learner-Central massive online course model that can’t revolutionize the system because the technological gap is too wide.

A study conducted by the University of Hyderabad revealed that the majority of students have no proper access to the internet. Universities and colleges have started online admission procedures, which is uncertain in nature. Indian student exclusive QS IGAUGE report titled ‘COVID19- a wake-up call for telecom service providers’ states that ‘the infrastructure in terms of technology in India has not achieved a state of quality to ensure the sound delivery of online classes to students across the country.’

Apart from technological disparity, various other maladies come in the way of easy access to online education. International labor organization estimates that 40 crore informal workers are vulnerable to fall into penury during the lockdown. Vivid images of trudging migrants, loss of livelihood, hunger, etc. blurs the hope of education among the suffering population. Malnourishment of children in the deprived section increased as the mid-meal ended with the closure of schools. An image portraying the plight of 15 children from Bihar’s Bhagalpur village prompted the state government to take brisk action. After the picture went viral and the National Human Rights Commission’s solicitous notice, the state government ordered the release of 5kg of ration and Rs358 of DTB (direct transfer benefit) to their guardians.

To intensify the adversity, some private, as well as public institutions have asked fees from the students for the facilities they can’t access from their home (e.g., Fees structure of the Central University of Pondicherry for the current semester include sport, library facilities, etc.). Above mentioned problems negatively impact the holistic development of children. Comparative scrutiny reveals that the digital divide vis a vis to rural-urban, men-women-transgender, inter-state, inter-regional, public-private institutions would make online education a commodity available exclusively for the privileged category.

Content Learning to Cognitive Skilling:

The Indian education system is mainly characterized by rote learning and a proctored examination. In this trajectory of syllabus-oriented content learning, children may lag behind acquiring basic cognitive abilities. According to the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), 2019 surveying 26 rural districts in 24 states, only 16 percent of children in class I read at a prescribed level. Forty percent cannot recognize letters, and 41 percent can recognize two-digit numbers. Infrastructural gaps in government schools are exposed as the report states that 41 percent of children read in private schools compared to 19 percent in government schools. ASER, 2019 suggests the educational institutions (especially those of the primary level) to focus on play-based activities that build memory. Reasoning and problem-solving abilities are more productive than an early focus on content knowledge. 4 important C’s- communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity are absent in online learning approaches. The Teacher and peer group’s physical presence is inevitable to ensure the active engagement of children in classroom activities. Sometimes, illiterate parents and siblings cannot compensate for the physical absence of teachers and peers in the online learning process. This works in favor of children coming from a literate and skilled background, mainly comprising the urban middle class. A supportive system called ‘Magic Pen’ introduced by a Kerala legislator from Pattambi constituency to enrich and enhance children with new ideas beyond the defined syllabus is laudable.

Central Board of Secondary Education’s (CBSE) selective removal of topics such as federalism, citizenship, secularism, nationalism, etc. from class XI textbook in the name of syllabus shortening policy is portentous. The government’s repugnant decision would generate a posterity oblivious of India’s democratic ethos and values and stunt the social-political development of the student community.

Way Forward

University Grant Commission’s insistence on conducting final year examination is presumptuous. Incessant deliberations and discussions about reopening schools with adequate safety measures to prevent a possible learning gap are irrelevant. The only thing the government and other stakeholders can do is to strengthen the sector with adequate infrastructural and faculty capacities to meet the demands of 15 lakhs schools and 5000 higher education institutions in a pandemic stricken India. A Harvard Global Education Innovation initiative, HundreEd, the OECD Directorate for Education and Skills, and World Bank Group Education Global Practice has formed a collaborative support system to provide countries with information and resources to tackle knowledge crises worldwide.

Collective toil steered by multiple stakeholders (government, NGO, civil societies) is the need of the hour to bridge the technological gap. Parikarma Humanity Foundation, a Bangalore based NGO which works for the education of children at an informal settlement, collected spare smartphones and used them to create a virtual school for 2000 children in 87 slum communities. Active engagement of NGOs, civil society, and proper allocation of CSR funds can reverse the narrative and dwindle the elusivity of inclusive virtual education platforms. Most importantly, educational institutions should refrain from asking a hefty amount as fees and fill the income gap suffered by teachers.

The decentralization of education can mark a positive impact. Devolving the onus of education to local governing bodies would make the teaching-learning process more workable and beneficial. Panchayat or locality wise mobilization of teachers, educated youth, parents, etc., heeding the pandemic situation to impart knowledge into the children would prove productive. This can effectively work if children are divided into age-wise small groups and assemble in a locality, maintaining government prescribed safety measures and guidelines to hear ideas, classes and indulge in activities (without breaching social distancing norms) given by volunteers. Such initiatives can enhance and enlarge the cognitive skills and understanding. It’s a perfect time for the autodidacts, university, and college students to sharpen their skills by reading, writings, and other novel activities and augment their understanding of the world. Effective assessment criteria are the other important dilemma annoying the authorities. Unlike foreign universities, the Indian system is infertile to implant open book examinations. Potent tools to measure students’ skills and achievements should be devised. Emulation of slow university movement can bring back novelty and ease student pressure in Indian institutions. To conclude, the government and other stakeholders in the sector should rectify all those hitches and ensure equitable distribution of knowledge among the student community during the global pandemic.

Featured Image Credits: Shanmukha Sai Uppala