Childhood in contemporary India

“Children are living beings- more living than grown-up people who have built shells of habitat around themselves”

Rabindranath Thakur

Childhood is the age through which socialization takes place to develop, transform and mould children into social actors. Though childhood is a natural stage lived by every individual, the ideas, norms, regulations and also the perception of childhood is contextual as they vary across time and society. How a particular society conceives of childhood is socially determined and varies distinctively from any other society. As in the context of India, owing to its diverseness in terms of language, cultural values, practices and beliefs, the notion of childhood is also manifold. There is no singular static understanding of childhood in India, again the definition of childhood here is a variable which changes with the different stratifications present in our country. Caste, class, ethnic, religious, regional and gender identity intersect with each other and form a particular discourse to define childhood and also the symbols associated with it. The expectations, the paths chosen and the goals defined for children by adults also depend on this diverse understanding of childhood. In these ways, the children who are virtually excluded from the public space are transmitted into social participants, carrying on their social identities through the acquisition of cultural capital under constant surveillance. The adult society shapes the goals for the children and design childhood in a way to create the future society as they envision it.

The experience of childhood also varies at every mile within the territory of India and has changed a lot in the contemporary times. Parental resources and one’s position in society can be identified as the major determinants of particular experience of childhood. India being a third-world country with the history of colonial hegemony; is still stricken by social milieu such as poverty, unemployment, and illiteracy and they have particular roles and ways of shaping the childhood experiences. Again, the concept of childhood is also politically created depending on contemporary ways of thinking.

There are also diverse topics related to childhood among which I have chosen the ways childhood is regulated through the process of socialization, specifically gender socialization and the crisis that distorts childhood experiences, for the purpose of this article.

Transmission of children into social actors

Socialization is an active and continuous process through which social norms are internalized (The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology, P.- 363). Although socialization is a life-long process, primary socialization mainly takes place at an intensified rate during childhood, a very crucial stage when the accepted rules and regulations are learnt, internalized and habitualized. It is the holistic process which links the individual to the collective life by moulding one into cooperation with social requirements (Nelly, 2007). In this process children witness a shift from internal regulation to external regulation through affective exchanges with primary care-givers whereby they develop the ability to understand other’s emotions and deliver their actions accordingly. Through parental validation, children undergo formation of conscience and internalize prohibitions by checking-back to the emotional expression of their parents as the guide of their conduct.

The process of socialization based on the aims and goals of a society transforms a child into a particular being. Here I would like to discuss one of Pierre Bourdieu’s themes (1930), the ‘habitus’ which according to him is the internalized disposition related to one’s socialization depending on the particular social milieu, that is the intersection of class, race and gender. It is something which is embodied and learnt through socialization on the basis of one’s particular social milieu, which in turn motivates one’s attitudes and ways of doing things in the “field” or the structured manner in which one thinks, feels and acts (Jenkins, 1992). So, it can be said that a child is socialized in particular ways depending on their social position, by which they embody particular attitudes or behaviours, which work at the level of mind and affect how they think, feel and act and therefore in certain ways would determine the particular type of adult they will become.

In contemporary India with the change in the structure of family and authority, there has also been a change in the socialization process of the children. Now preschools and schools play a more prominent role in this process and there has been an increase in the pressure of the parents of middle-class families to admit their children to renowned prestigious schools for which training starts at a very early age. Again, in this advanced stage of capitalism owing to the rapid process of commodification, children are socialized in particular ways by the family, school and the state, as the next generation of the workers through education.

Her childhood and his childhood

“One is not born, but rather becomes a woman” (Beauvoir, 1949). We are made gendered beings by living in the society and performing our accepted gender roles as created by the social institutions. Gender socialization is one of the earliest and powerful processes by which an individual’s identity as a particular gendered being is developed by living in the society and participating in the social institutions which later on shape their life choices and aspirations. In the Indian context there are various such institutions but here I would like to discuss primarily the role of family in shaping children’s gender identity.

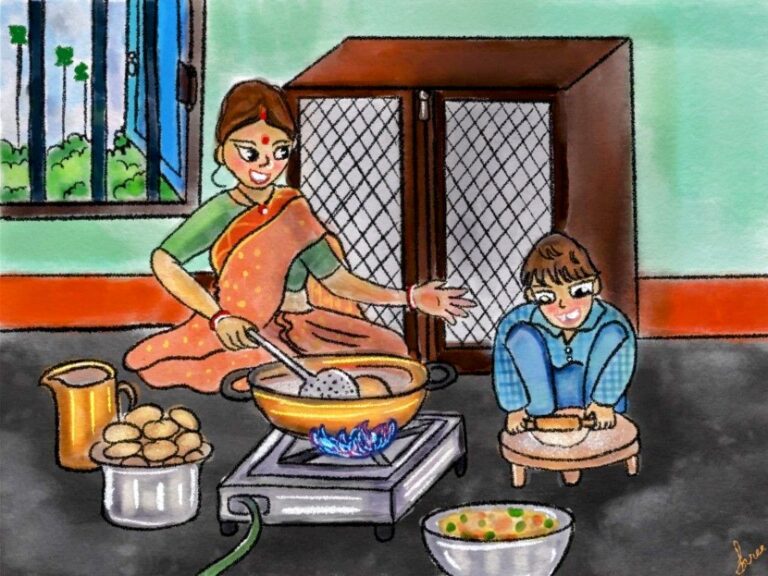

Though sex ratio of India has improved in the contemporary times as per the census of 2021 (1020 females to every male) in comparison to the census of 2011, gender inequality is very much imbibed in the consciousness of the people here. A girl child in the predominantly patrilineal and patriarchal society of India experiences a completely different childhood than a boychild, where she is prepared to become a wife and a mother. Socially created and widely accepted female traits such as politeness, submissiveness, caring etc. are developed in a girl child through the process of socialization by training her gender performance in her everyday life. Similarly, the traits of hegemonic masculinity are demanded from the boys and are imbibed by them as the society wants to maintain its structure and reproduce its practices on the next generation

Family plays a major role in gender socialization. Since childhood the members of a family emphasize particular roles and attitudes on the basis of one’s gender. Children often come across several comments in the family on the basis of their gender which act as very powerful messages which lay the foundation of how young people will view their future career options and also affect their self-perception. Here I myself being a member of a Bengali middle-class family would like to cite some personal observations to explain the role of family in the socialization process, which although might be very contextual, will act as an example. In my house, I have two cousins, a girl (three years) and a boy (four years) and I have observed that the expectation of the family from each of them is very different and they are praised or scolded for different activities, for instance the girl is expected to perform many of her activities (like eating, bathing and other random activities) on her own and are remotely praised if she manages to perform them correctly whereas such exceptions are very low in case of the boy. Both of them have developed a pretty clear conception of the gender they belong to and a detailed observation of their activities, the games they play and their narratives would show that they perform their roles accordingly.

Often parents have different attitudes towards their daughters and sons and also have different expectations from them, which affect their self-confidence. Girl children are often considered to be a burden for a family, especially in certain specific regions of India. Female infanticide is still in practice as 17 infanticide cases are reported in the state of Tamil Nadu in the year 2020, followed by the state of Maharashtra with ten cases of infanticide that year (Statista Research Department, 2021). Such unwantedness affects the childhood of girl-children and they are also discriminated against in the household or are provided with a smaller share of food and other resources. Daughter’s academic qualifications are not given much attention by the parents, as in the words of Leela Dube (2001), girls in Indian patrilineal families are perceived as, ‘transferable’, ‘a guest in the parental home’ or a ‘bird of passage’, thus investing for the education of a girl, who after marriage would belong to another lineage is often not seen as a very rational idea and thus the main focus is on teaching her household activities thereby preparing her for marriage. But with the evidence of some amount of ethnographic findings, I would like to share that such trends are changing in contemporary middle-class and also lower-class families as the parents now are considering and investing on their education. Academic qualifications of girl children are also being emphasized by the parents who now want their daughters to be employed but more or less marriage remains to be the final destination of the female population. On the other hand, sons being considered to be the gift of the family are socialized in a way so that they can undertake the economic responsibilities of the family later on. Such expectations of becoming the future bread-earner of the family often pressurizes them and takes away the essence of their childhood.

Other agents such as educational institutions, media and peer groups also act in definitive ways to shape a particular childhood through regulations, monitoring, representation and exchange.

The lost childhood

Now in this section of my article, I would like to bring out some of the issues related to contemporary India which have led to the childhood crisis. Childhood, as already being discussed, is not a homogenous experience for every individual. There is compartmentalization of childhood into different sectors and for many, experiences of childhood bring in traumas and taboos which they carry through-out the life.

Child-labor is one such broadly practised issue in the Indian context which destroys millions of childhoods thus demolishing the future of the individuals as well as affecting the development of India in the long run. India, the world’s largest democracy, ironically has the most robust legal framework in terms of protecting the children from the vagaries of the labor market and still has the highest incidence of child-labor in the world (Mangla, 2009).

Inequalities, lack of educational opportunities, slow demographic transition, tradition and cultural expectations all contribute to the persistence of child-labor in India. As per Census of 2011, among the total child population of India in the age group of 5-14 years, 3.9% that is 10.1 million are working either as main or marginalized workers (Fact sheet, 2017). It has also recorded that more than 42.7 million children in India are out of school. This rate has even increased ever since the pandemic which had led to the nation-wide lockdown and has totally ruined the socio-economic condition of the country. It has further widened the inequality of the society in terms of access and significant dropouts from schools took place leading to an increase in the illiteracy rate. Drop-out rates are higher among female students throughout India (UNICEF, India). As per a poll conducted by UNICEF on International Women’s Day 2022, it was reported that at least 38% of respondents knew of a girl who had dropped out of school, while 33% respondents said that the girls who had dropped out of school were engaged in domestic work. 25% of respondents also reported that the girls who had dropped out had got married. Such practices like child-labor, child-trafficking and child-marriage impede the children, the future of India, from gaining the skills and education needed to gain opportunities of a decent life. Thus, very often, children in the Indian context being unable to meet the socially and culturally defined goals through the institutionalized means, fall prey to deviant activities (Merton, 1938). Children being pressurized by the social structures sometimes search for solutions in drugs thus leading to juvenile delinquency.

Malnutrition among children is another such problem which disturbs the holistic growth (both mental and physical) required during childhood and makes childhood more vulnerable. The experience of malnutrition in India has further increased, owing to the pandemic, as suggested by recent studies, around 115 million children in India are at a risk of malnutrition in the present situation. (Singh, 2021). Physical abuse is also a very common experience of children in contemporary India which brings in a long-term effect on their mental growth and identity formation. This along with the issues rising from over pressurization of children by parents, lack of freedom and voice, competition with peers, effect of exposure to the encoded version of mass media further mechanizes childhood, mainly in middle-class families of India. The sentence used by Ellen Keg in his book, “Century of the Child” (1909) can be mentioned in this context- “Instead of the century of a child we got the century of the child professional”. Such competitions take away the fluidity and innocence of childhood often leading to chronic depression among children.

Conclusion

Proper development of a child cannot take place in isolation, so the pandemic has further affected the growth of children in India by also distancing them from the open fields and blue skies. All these crises demand a detailed study in the field of child’s rights. Childhood is a crucial stage which forms the roots on which the whole life of an individual depends. Thus, childhood needs to be protected from both extreme luxury and extreme crisis and it also needs to be sheltered from abuse, violence and all the negative consequences as we carry on childhood memories throughout our life. And also depending on the socialization and internalization in the childhood days we form the conception of ourselves which though may change over the course of life, the basic understandings remain the same. Thus, the creation of a proper fluid pedagogy is very much required where the children will receive space and autonomy to develop and will also learn to question and think independently. The agency of children should never be curbed through constant restraints and at the same time there should be some effort by the Indian government to provide a homogenous childhood to the children where everyone will receive equal access to resources irrespective of any stratification so that they could have equal opportunities of development.

References

- Stromquist, Nelly, P. 2015. Gender Socialization in Schools: A cross-national comparison. Unites Nations Educational, Scientific a Renold, E. (2001). “Square-Girls,” Femininity and the Negotiation of Academic Success in the Primary School. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 27(5): 577-588.

- Dube, Leela. 2001. Anthropological Exploration in Gender. New Delhi Thousand Oaks London, Sage Publication.

- Jenkins, R. (1992). Pierre Bourdieu. London: Routledge.

- Beauvoir, S. (1986). The Second Sex. New York: Vintage Books

- Mayall, B. (2000). The sociology of childhood in relation to children’s rights. Int’l J. Child. Rts., 8, 243.

- Kochanska, G. (1993). Toward a synthesis of parental socialization and child temperament in early development of conscience. Child development, 64(2), 325-347.

- Abercrombie, N., Hill, S., & Turner, B. S. (1986). The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology. London: Penguin.

- Haralambos, M., & Holborn, M. (2000). Sociology: Themes and Perspectives. London: Collins.

- Kochanska, G. (1993). Toward a synthesis of parental socialization and child temperament in early development of conscience. Child development, 64(2), 325-347.

- The children who quietly dropped out of school. Link

- Increase in school dropout rates for girl child is alarming, states UNICEF India. Link

- India’s Sex Ratio Stands At 1,020 Females Per 1,000 Males: Economic Survey: Link

It gave me a solid perspective of childhood in India. The concept of childhood depends on the culture of the society is one of the strongest arguments made by the author. In additions to this appreciation, the author successfully depicted that, the gender socialization starts from an early age, differentiating ‘his childhood’ from ‘her childhood’.