Re-shaping Women’s Agency: Silenced Voices within the Periphery of Northeast India

Cihnnita Baruah is a Doctoral Candidate at the Centre for the Study of Law and Governance, Jawaharlal Nehru University. Her area of interest is social movements, identity politics, gender, and media. Pratisha Borborah is Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Cotton University. She is also a Doctoral Candidate at Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Read out this Theel for me”]

Ethnography refers to the collection of experiences, narratives from the field that lies behind theories or stories that remain unheard. With the advancement of social sciences in India, new areas of women’ studies have formed ground from diverse contexts. Gender issues are looked upon from intersectional perspectives to understand how different categories like religion, culture, politics and economy are shaping women’s agency. Different narratives are seen and analysed from the lens of historical complexities, societal construction of inequalities, biographies, etc. It is in this context, that this paper looks into how political and economic spaces that reflect and promises women’s empowerment need an in-depth sociological imagination.

Amartya Sen defines agency as the freedom that an individual exercise, and because of this, they can do and achieve goals which they feel is important for them. Within the discourse of social science research, the agency is synonymously analysed with being a person. It is interchangeably used with other concepts such as freedom, autonomy, rationality and moral authority. In fact, even in analysing women’s history — agency, activism and organisation are constant themes. Both individually and collectively analysed, these variables make up to be important elements and provide a valuable framework for examining the life and cultural experience of women. Analysing women’s history through the lens of agency provides us with a holistic understanding and leads us to consider specific ways by which women have organised themselves and have taken part as activists to challenge, resist, overthrow or gain entrance to social structures and institutions that had ignored, exclude, disadvantage or penalise them. It is important to find out the functionality of these forms of agencies in the present context. In this framework, this article is an attempt to question this idea of agency through narratives, and the struggles and challenges faced by women in this process. Assam in the North-Eastern part of India in the study here.

There is an abundance of literature in India which tests the number of programs actively working towards understanding the shift in gender norms (informal rules that impose expectations about behaviour dependent on gender) or improved women’s agency (their ability to define and act on goals), role in decisions making and also participation and engagement in the economic structure. Here, the authors are presenting two different scenarios reflecting on how despite women’s participation, their voices are quiet.

This points towards two questions:

- What is ‘agency of women’ in reality at the grassroot level?

- How does women’s agency gets reformulated within different social structures?

The first setting is a weekly market in Assam. This is a market situated in a Karbi village in the capital city of Assam run by the Karbi community. Karbi is an ethnic community in Assam found both in the hills and plains. Weekly markets are known for the maximum presence of women as vendors. They are traditional markets that still exist in different parts of the region. Vendors (tribal and non-tribal) mostly women travel from rural to urban areas every week to sell their commodities. These markets reflect how women are given a space for building up their own identity and independence. They bring their own choice of commodities, sometimes the traditional clothes they weave on their own. But there is a blurred line between these women locating their agency and the patriarchal expectations upon them. First, this market is completely run by men. No Karbi women are allowed to be a part of the market association, even though this market has a huge number of women vendors. Secondly, some vendors coming to the market to sell their commodities is not a choice they look for. Instead, it is a responsibility they need to take for their family. As Barry Barnes writes, “There is clearly a strong link between ‘choice’ and ‘responsibility’”. These women although tend to choose to be a part of the market, their choices are always determined by societal and family responsibilities. Whether it is the choice of work, timing, process etc, her kind of work is determined by what kind of responsibilities she has to offer. While the local Karbi women of the village are expected to be with the children and family rather than spending time being associated with market authorities, women vendors coming to the market need to be a part of the informal labour for their family. These stories implicate how public/private spaces construct women’s agency.

Agency is not a fixed category rather it is the study of women’s mobility that reflects the dichotomy of gendered spaces and its impact on the agency. Thus, contestation of space and gender has become one of the important concerns for understanding both urban and rural, formal and informal sectors, etc. It not only explains the division of labour in our society but also the construction of identity, status and spatial power and inequality. Interestingly, in spite of the fact that women come out of their household to earn for their family, ‘headship’ remains under the male member. Most of the women being uneducated are dependent upon the male members for any financial decisions. These women have no bank accounts or any other financial savings, making them vulnerable every day. In spite of the fact that they are the sole earning members of the family, headship goes to the male without being questioned. This brings to the debate that Bourdieu reflects upon ‘structure’ and ‘agency’. How these women reflect upon their agency is not just based on mental construction, rather it is a social habitus that shapes her experience in everyday life. Women accepting the fact that finances need to be seen by the male member explains how “a gendered view of the world is stored in our habitus; the habitus is profoundly and inescapably shaped by a pattern of classification that constructs male and female as polar opposites”. Thus, external structures are internalised in the habitus. Nevertheless, there are multiple structures within societies and the relationship of the individual to these structures influences the agency of an individual.

The history of Northeast India is one of the struggles for ethnic self-determination by the different indigenous communities residing here. The Sixth Schedule which is in operation in this region allows for the formation of Autonomous District Councils. Autonomy is expected to act as a platform for percolation of the ethos of democracy to the grassroots level. As such it is supposed to take into consideration the aspirations and demands of all the members of society. Thus, the second scenario where we can analyse agency is within an autonomous setup. In this context, we can look into the case of the Bodo women and their participation and representation in the political setup.

The Bodo women have shown an active involvement towards the cause of the movement and other activities. However, the social structure of Bodo society is primarily patriarchal with very few elements of matriarchy. In the Bodo society, women have considerable authority in certain social and domestic affairs. Further, even in terms of participation of Bodo women in the political field it too began around early 1974-75 with the beginning of the language movement (also referred to as Roman Script movement). In addition, the formation of the women organization i.e. the All Bodo Women Welfare Federation (ABWWF) acted as an important platform which encouraged greater participation on part of the women. This forum inspired women to take part in various social and other allied activities and also encouraged them to take active roles in the political fields. Thus, the Bodo women were also seen to be equally active along with their male counterparts.

However, a closer analysis highlights that women have not received due recognition, mostly because of the societal patriarchal structure of the Bodo society, which acts as a hindrance towards the development of Bodo women. Especially, after the signing of the Bodoland Territorial Council Accord in 2003, divisions appeared within the political sphere too. The elections displayed a power struggle amongst the already fragmented community. Issues arose regarding the selection of candidates. The All Bodo Women’s Welfare Forum (ABWWF) was forced to take a backseat during the elections, and not a single women candidate could contest for the Bodoland Territorial Council elections, barring the fact that ABWWF had played a pivotal role in the Bodo Movement. Erstwhile women cadres of the ruling political party and founding members of ABWWF expressed their displeasure with this discrepancy and pointed out that women were denied leadership positions, irrespective of their service for the cause of the movement.

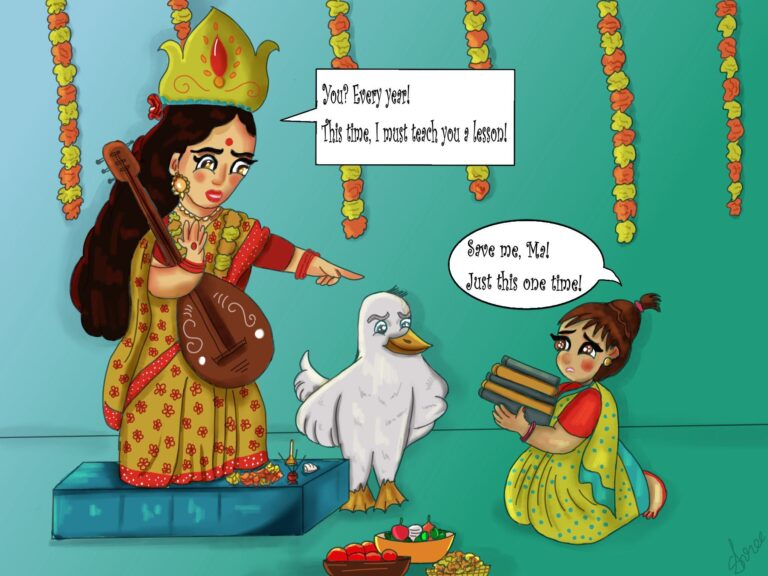

Further, another hindrance to exercise women’s agency arises due to the nexus of tradition and modernity. Women are entrusted with the role of a ‘culture preservator’, highlighting how regarding issues of cultural preservation, the question of gender equality takes a back seat. There are also instances where the Bodo society, which still questions the practice of exogamy and perceives inter-caste marriages to be an infringement to their cultural values, outcast families because of those marriages.

Thus, women’s empowerment is a multi-dimensional concept located at the intersection of tradition and modernity, and the constraints and possibilities that emerge within this nexus. Modernity and tradition have always had an entangled relationship. The dialectics of tradition and modernity in a way seem to confine Indian women. Culture as we commonly understand in the context of India is close to tradition while modernity manifests itself with various changes in the lives and activities of an individual. Women are more or less seen as the representative of Indian culture. As time passed, the responsibility of maintaining the uniqueness of culture was bestowed upon women. The conduct of women regarding morals about proper deeds has been central to social concern. Categorical thinking of modern women as good and bad according to their activities exists in every society of India. As such, controlling and monitoring of women’s movement and behaviour has always existed in society. This sense of control can be partly blamed for the emergence of the categories of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ woman, which is one of the worst forms of violence that exists in almost every society, justified in the name of culture, tradition and identity.

The control and monitoring faced by women is not only an assault on women, but it also restricts the freedom of women in a public space. In the societies of Bodo and Karbi, women are recognised as a symbolic representation of culture and ethnic identity. Issues raised for women’s individual agency are treated as a matter of negotiation or as a rebellion which questions the existing norms of class, gender and other social constructs that mediate, but do not necessarily ultimately determine, access to authority and power. Thus, one needs to closely analyse agency while trying to comprehend the sense of empowerment and representation that women seek.

An analysis of the society through narratives points out that although technically these women may appear to be living around in an environment free of certain social evils like dowry, female infanticide, but in reality, it erects a false notion of gender emancipation as women are still the victims of gender-based violence. A closer analysis is required to comprehend the exercise of agency by women in tradition, modernity and nationalism.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons