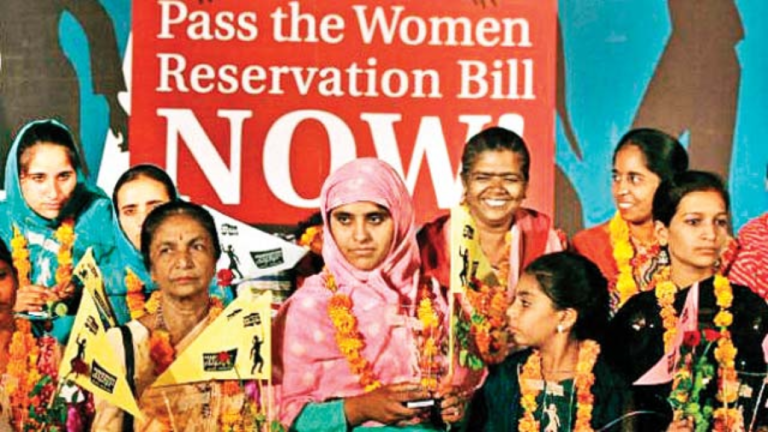

Women On Their Own: On the Women’s Reservation Bill

Dilip Simeon is a teacher and taught at many universities across India and the world

(This article was written in May 1997)

One of the memorable utterances of Sharad Yadav in his outburst against the women’s reservation bill was his scorn for the idea that balkati mahila (presumably he was not referring to sanyasins) could represent “our women”. This gave the game away, for it showed the deep insecurity among male politicians at the evaporation of their control over women. In this matter, the leaders of the OBCs are no different from communalists of every hue, with their notorious efforts to impose “traditional” norms upon “their” women. References to the physiognomy of one’s interlocutors are considered offensive in any civilized conversation. It is a telling commentary on the state of affairs that coarse behavior towards women on the part of a senior leader of the ruling party in Parliament arouses only mild demurral rather than outrage.

Fifty years after independence, women in the Indian parliament numbered 7% of the total, the highest being 8% in the 8th Lok Sabha. If this is not a shameful indicator of institutional infirmities, I don’t know what is. There has been a 47.6% increase in reported crimes against women between 1990 and 1995. In 1995 there were 4659 dowry murders (why are they called “dowry deaths”?), and 12,458 cases of rape. If the interests of “weaker sections” are safe in the hands of Yadav and Co., there is very little to show for it. The will to power of the OBC elite exists in inverse ratio to their capacity for statesmanship. This is unfortunate because the movement of the middle castes for political power has been one of the hopeful developments of recent decades. But their successes seem to have strengthened patriarchal forces within peasant communities – witness the recent cases of young women from the backward castes being murdered by their caste panchayats for choosing their own life partners. OBC leaders do not condemn such events, because social reform has always taken a back seat to political power. The demand for women’s representation has emerged not because of male goodwill but because of a global upsurge in women’s mobilization and the successes of the women’s movement in India over the past two decades. The fact that women forced two state governments to introduce prohibition (even though one of these has since backtracked), shows that they are capable of using democratic institutions to influence political events.

Half of the human race possesses characteristics of a disadvantaged minority, with social disabilities that show no sign of being eroded without institutional safeguards. Reservations for women have an explosive potential for transformation. An opinion poll in August 1996 showed a massive 75% support among women and men for such reservations. The experience of quotas in panchayats since 1993 has shown a groundswell of enthusiasm. A survey from Madhya Pradesh shows that the presence of women in panchayats led to greater urgency towards the provision of drinking water, the enforcement of the presence of schoolteachers, the provision of health facilities, legal literacy, and the protection of the environment. Dr. Vina Mazumdar has a similar assessment with regard to the experience of the Nari Vikas Sangha of West Bengal and other women’s mass organizations. Women representatives in localities she observes, tend to have an innate sense of responsibility and have demonstrated a strong awareness of issues such as communal violence and lawlessness, the harm done by chemical fertilizers, pesticides, and monoculture, and the availability of water. They also have an earthy understanding of social issues – Punjabi village women made a connection between alcoholism and the patriarchal upbringing of sons.

The demand for an OBC segment within the women’s reservation is intended to obtain reservations for OBC men under threat of sabotaging the Bill. The constitutional provision for SC/STs will remain in place within the women’s quota, but proportional reservations for OBCs and minorities will carry separate ramifications. There is no estimate for OBCs, as the last caste census took place in 1931. The Mandal recommendations were not about proportional estimates, since OBC’s number is well over 50% of the total population. As for minorities, a number of the Mandal castes are Muslim in any case – communal reservations in legislatures will raise a hornet’s nest. Another debate will completely sidetrack the question. Gender discrimination occurs in all castes and communities, and is autonomous of other forms of discrimination. Issues concerning women as a group exist apart from matters of ethnic identity. These range from dowry murder, female infanticide and domestic violence, to education, laws governing migrant labour and informal sector work, the availability of child care, maternity benefits, and the provision of toilet facilities in public places. Reservations are intended to correct historical injustices. The oppression of women is a historical injustice if ever there was one. The principle of the autonomy of gender-related issues and the human rights of women has to be brought home forcefully to those who control legislative institutions. Nothing prevents them from fielding OBC candidates for reserved seats. Aren’t they confident of the loyalty of “their” women?

National institutions tend to be distant from issues that concern localities. Yet a more equitable representation of women in legislatures might complement the panchayat reservation and correct this alienation. The presence of a bloc of women in Parliament will make legislators more amenable to amending laws that make rape trials humiliating for victims and more sensitive to issues that manifest the sub-human status of women. At the very least, it will reduce the number of goondas in legislatures and the expenditures incurred to guard persons from whom we need protection. In turn, the disabilities suffered by panchayats in terms of a lack of adequate powers might be overcome with greater administrative devolution – which will become easier with the presence of sympathetic MPs.

Why 33%? Questions about this “magical” figure have a snide ring. It is indeed arbitrary. But 33% is a sight better than 5% or 7 %, which is all that women may expect under the current dispensation. Indeed, 33% will be a major victory in the struggle for social democracy. Citing the tendency of male bus passengers to treat non-reserved seats as their preserve is frivolous – one does not remain in a bus for years, nor have the opportunity of arguing with one’s interlocutors. And surely the possibility of a more equitable distribution of seats in buses would brighten if there were a larger number of women demanding it?

Patriarchal oppression will not end with reservation, nor is thoroughgoing gender justice possible under the capitalist system. Capitalism is a seemingly objective mode of control over human labor which despite being muted by impersonal market forces, perpetuates violence, chauvinism and patriarchy. Nonetheless, combatting patriarchy in each of its bastions is necessary in the ongoing struggle for social democracy. The women’s movement in India is at a crossroads – the health of Indian democracy depends on its struggle for the Reservation Bill. A Lok Sabha elected on false promises is now seeking to extricate itself by procrastination. Mr Gujral should not hesitate to go to the country on the most far-reaching constitutional development since 1950. It will stamp him with the mark of a statesman and redeem the egalitarian promise of Indian democracy.

An afterthought. Take a shave, Sharadji. How long will you keep hiding behind the fungus?

Featured Image Credits: DNA India