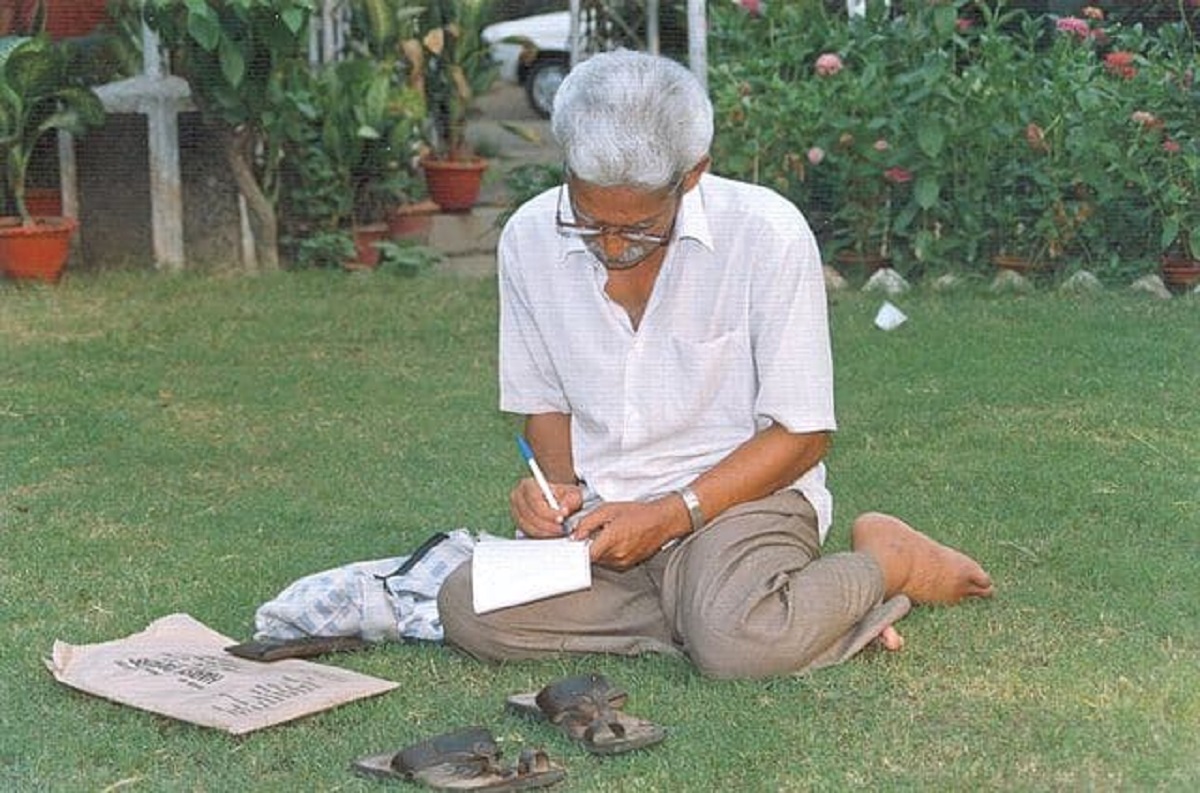

Poet Varavara Rao – A Chained Passion

Revanth is somebody who is either a hermit who has made his hostel room his haven or a wanderlust who has hit the road. When he is not reading books, about books, or talking about them he is engrossed in classic Telugu films.

Playwright Bertolt Brecht, wrote in his ‘Life of Galileo’, “Unhappy the land that is in need of heroes.” Our moment in our nation’s career has churned month after month, a hero from civil society – and unhappy, it is truly. For some time it was the Dalit critic Anand Teltumbde and then, Safoora Zargar and now, as he is reluctantly placed in hospital (having tested Covid-positive), it is Varavara Rao, the life-long Maoist sympathizer, and Civil rights activist. To much of the country which was – for the greater part of his active political life – oblivious of his thrust, he has become more or less the face of the state’s all-powerful, crude and thirsty grip, with little moral considerations, as its unfortunate victim. I have, in this short introduction, described him with a few qualifiers. But two serve him the best, and capture his breadth of imagination- compassion, and virtually his raison d’etre. He has been, in that above-said greater part of his active political life, a poet in captivity.

Pendyala Varavara Rao was born to a middle-class Brahmin family in Warangal. His passion was never lukewarm; just reading his writings can be an immersive experience instantly. His enchantment with the Marxist creed of thought began with no less a historical moment than the uprising of Naxalbari and closer home, the rebellion in the Ghats of Srikakulam. Varavara Rao, who had served as a school teacher and had been running the literary journal Srujana for his Saahithee Mitrulu (Friends of Literature) society turned one of the co-founders of the acclaimed organisation VIRASAM (‘Viplava Rachayitala Sangham’ or Association of Revolutionary Writers), which featured also, Mahakavi Srirangam Srinivasarao (popularly known by his nickname Sri Sri). As a critic, translator, and explainer, he has penned several anthologies of poetry, novels, and works of social and political theory.

In the troubled history of Maoism in South India, due to his affinity to Maoist groups, he has been their default emissary in public and urban life. Naxalbari was not only a high tide point for ideologues and progressives like Varavara Rao but also in the history of Indian criminal procedure. The state has attempted to repress the Naxalite threat and establish law and order. This attempt has unleashed several laws, which in their loosest interpretation (also the most usual kind of interpretation) are nothing short of draconian, including: the UAPA (Unlawful Activities Prevention Act), TADA (Terrorist and Disruptive Activities Prevention Act), and MISA (Maintenance of Internal Security Act). On account of these acts, he has faced many charges over the years including terrorism during the emergency, the Secunderabad Conspiracy Case, and currently the Elgar Parishad Case. He is said to have schemed an assassination attempt on the Prime Minister in the congregation preceding the ‘Bhima-Koregaon Violence’ incident. As a result of these various charges, he has by now spent nearly ten years in prison and many countless hours of court hearings. As he writes in his memoir ‘Captive Imagination’, “life imprisonment [is] interpreted as imprisonment for life.”

Varavara Rao has a vision that is all-engulfing. Sri Sri famously wrote in his poem ‘Rukkulu’ (a term for poetic offering from where also comes ‘Rigveda’), usually translated to English as ‘Poetics’: “Teeny, Weeny Pups/ Eeny, Meeny Ships/ Sheeny Shiny Soaps/ All world silent and noisy/ Is material for Poesy.” Sri Sri’s wisdom would surely have rubbed onto Varavara Rao in his time at Virasam. Rao, of course, meditates on comrades and the repression that they face by way of the shackle, bars, and the gun, but also the ills of parliamentarianism, America’s war against Iraq, the governments of Chandrababu Naidu, and K Chandrasekhar Rao, Nala-Damayanti and the Ramayana, the tune of Chaudhvin ka Chand, and the 1951 Telugu film Malliswari. Disparate entities become to one another objects and standards of simile. Read, for example, this line from his ‘Captive Imagination’ that describes the censorship of letters that flow to and from the world of the prison.

Love’s message reaching second-hand is not unique to me after all. It happens when people lose power. It happened to Rama and Sita and to Nala and Damayanti, to all those who were objects of either the anger of the state or its mercy and also to the yakshas and yakshinis, and to Malli and Nagaraju.

And he breaks into a poem on the pain of captivity and distance from one’s loved ones:

The doors of your heart still untouched by feeling,

Letters gleaming with desire,

Currents flashing over my body from your eyes.

What shall I say to you that can be sullied by other hands?

Freedom is Rao’s greatest calling and much of his poetry is a painting of liberty in its pure crystallised form or the lack thereof. His most well-known metaphor for the freedom in being was the ocean, Samudram.

“What shall I say of the ocean that I witnessed

Hear in the eyes of my television

And see, while your ear rests on my chest

Listen to that conversation-

Of the ocean and my recorder on the tape

Listen

While my blood echoes

The exhale of the ocean

And listen

As my pants shuttle

The faith of the sea” (Translation mine)

The imagery of this poem thickly resonates with its inverse, the poem that is in circulation with the title ‘Bard’ that depicts the shrillness of state repression. Like Varavara Rao’s blood and the sea, Samudram speaks with Bard.

When timeless morality is in place

And as pitch-black clouds of time strangle the throat,

Neither blood trickles nor tears drop.

Raindrops surge into a storm.

Absorbing mother’s tears of sorrow…

But in the torrent of unfreedom there was still hope and Bard goes on:

The poet’s musical message

Escapes the prison walls.

The throat emits a tune.

The tune turns into an anthem of freedom. (Translated by my friend Chaitanya Suraj)

Varavara Rao’s credentials and loyalty to the Marxist-Maoist strand cannot be understated. In articles, poems, speeches, and interviews, he has consistently iterated his faith in ‘scientific socialism’ as it were. He saw in Marx’s study of historical phenomena, some essential truths. Poem after poem, this allegiance is resounding. As if a bounce-off from Bard, the Reflection too talks about the mettle in dissent but appears to differ in that class struggle which will live on, independent of the individual’s pen.

I did not supply the explosives

Nor ideas for that matter

It was you who trod with iron heels

Upon the anthill

And from the trampled earth

Sprouted the ideas of vengeance

…

When the victory drum started beating

In the heart of the masses

You mistook it for a person and trained your guns

Revolution echoed from all horizons. (Translated by K Balagopal)

Or consider this, where both the peasant-worker revolution and its colour paint the sky as well, the sky which in an earlier poem, cast itself upon the world.

Oh Enemy,

One fine morning in the wee hour,

After tying behind the back

The hands that fought for sunrise

After blindfolding the eyes

That looked for sunrise

After putting the noose around the throat

That spoke for sunrise

After pulling the trigger

You turn that side

Only to find the sky blood red

In that crimson lap

Someone’s eyes have just opened (Translated by N Venugopal)

Varavara Rao must be applauded for the versatility in his work. While in Samudram he appears to speak in the level of the abstract, as a romantic afloat and a part of nature, all of his poetry was a response to particular incidents. Some incidents spoke louder than others in the poems that they were inspired from. One well-known example of such a poem is titled Butcher. In 1985, a Muslim butcher in Kamareddy, Telangana testified the brutal harassment of a young man by police for protesting against a particular ‘fake encounter’.

I am a vendor of flesh

If you want to call me a butcher

Then that is as you wish

I kill animals daily

I cut their flesh and sell it

Blood to me is a familiar sight

But

It was on that day that I saw

The real meaning of being a butcher,

That young boy blood congealed

In the fear that had gathered in my eyes

His voice went dumb

With the words that would not leave my lips

While always having affirmed his belief in an armed struggle, a fraternity of all beings was essential to Varavara Rao. There was always peace in sight, and a struggle must culminate in civility. This is not unheard of even in the Marxist tradition. In 1923, Leon Trotsky (now reviled among conservative Marxist circles) went as far as to write an article titled ‘Civility and niceness as a necessary lubricant in Daily relations’. And how, would such civility be cultivated between warring factions. The answer, I think, lay to Varavara Rao in nuance. One ought to march alongside the Adivasi but the struggle was not against the policeman, but instead a state apparatus which flings CRPF personnel that it has at its disposal. In the Telugu newspaper Andhrajyothi, he described prevalent rhetoric around the Naxal question in 2006, in an article titled ‘Will the human essence sustain?’: “If you are not with CoBRA, you are with the Maoist. If you do not justify police activity, you justify Maoist menace…” Varavara Rao saw George Bush’s “You’re either with us or against us” as a convenient motif to explain the public imagination of all dissident movements. Hence Baghdad was a common setting for his poetry.

In the Telugu poem titled ‘The Crescent upon Baghdad’, he placed the poignant stanza:

I like Arab fanaticism more than American democracy

A year and a half ago

Sixty years of American occupation

When I said I shall try,

You said that I am a defender of Bin Laden

When I declared that I detest Internation Monetary Fundamentalism

No, you said

That I sympathise with Islamic Fundamentalism

You say again today, “Yes,” in Saddam’s words,

“That criminal George Bush and his son George W Bush

Shall fall to doom.”

Having read these verses from Varavara Rao, it is not hard to see why government after government chose to incarcerate him. His words are shrill, like the force of the state; and they shock, and scandalise. They tread the roads that few other writers may dare to. In an earlier paragraph I pointed out an irony between his two poems of ‘Reflection’ and ‘Bard’ since in one, the individual is minimal, while in the other, the poet’s voice is omnipotent. The resolution lay in the later lines of Reflection. Varavara Rao seems to have written about himself when he chose to break the wall between person and community, literature and movement.

The enemy fears the poet,

Incarcerates them,

Sentences them to death.

But by then, the poet is already breathing

among the masses, in the form of their message.

“You don’t arrest Voltaire.”

Charles De Gaulle on Jean Paul Sartre’s arrest in the Civil Disobedience of 1968.

Featured Image Credits: Pen

Views expressed are the personal views of the author