Prashant Kishor: India’s ‘Godfather’ grounded

Srinath is the Founding Editor of The ArmChair Journal. Currently at the University of Chicago, he is also an alumnus of IIT Madras, Ashoka University, Rishihood University and Purdue University.

Some states in India attract particular attention with respect to their state elections. One of these states is Bihar. Others, I believe, include Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Kerala, Tamil Nadu. Unlike elections in states like Jharkhand, Telangana, Odisha, somehow, the attention of the national media shifts disproportionately towards these elections whenever they happen. It appears as if the whole of India is interested in them, though I believe it is just a media bubble more than the national perception.

I was never particularly interested in them as every election is only as important as much for its people. But for professionals in political consulting, Bihar elections aroused curiosity for another reason. At this time, it was Prashant Kishor, the pioneer of the formal political consulting industry in India, contesting. I had referred to him a the ‘Godfather’ for his mysterious relationship with power as he supported many Chief Ministers to hold power.

A disclaimer

Political strategy always comes ahead of the actual event taking place. On the other hand, political analysis comes after the event is finished, with the advantage of hindsight. For example, many times, it is in hindsight that analysts see an electoral wave. Who would have credibly predicted a wave in the Maharashtra assembly elections 2024? Analysis is far easier compared to Strategy. This article is a simpler analysis. But an analysis about strategy.

As we don’t have access to what happens behind the curtains during elections, I would like to assume that the communication of Prashant Kishor for his pitch was intentional, rather than a compromise on his own autonomy – or that he was a b-team or a pawn in someone else’s hands. As much a strategist he was, I would like to assume that Prashant Kishor made full efforts to become the Chief Minister of Bihar as the best case scenario, though he may have packaged Jan Suraaj as a social movement rather than as an approach for political power. I would like to read this social positioning of Jan Suraaj as a strategic decision for political power, rather than as an advocacy effort, or a social movement for cultural or political change.

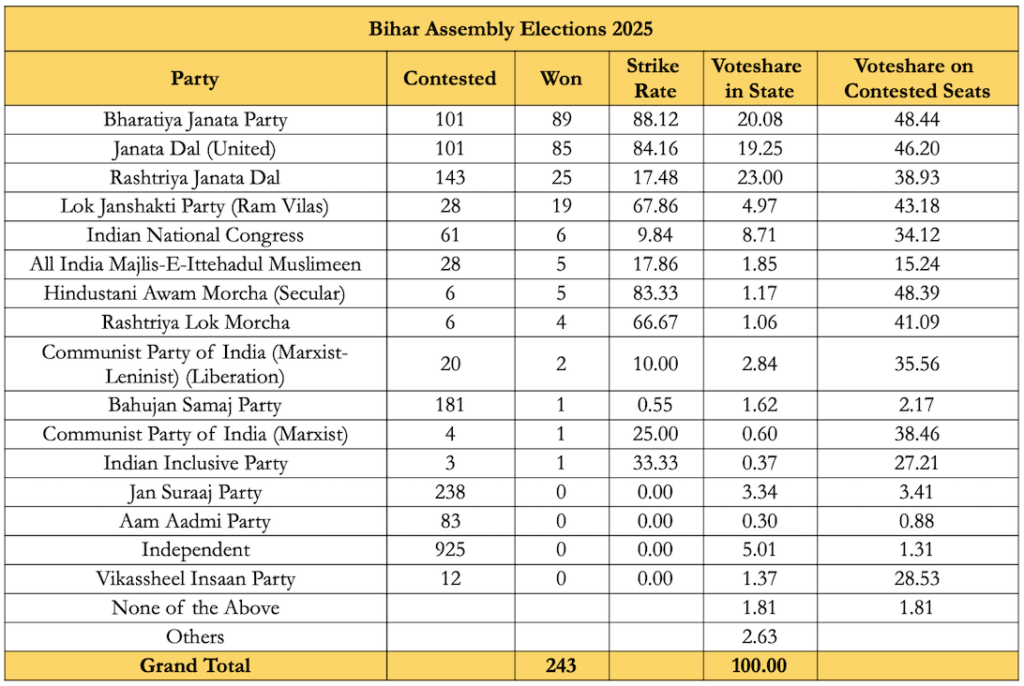

Facts first

To clarify facts first, Jan Suraaj Andolan was launched as a social movement on Oct 2nd 2022 on Gandhi Jayanti and the Jan Suraaj Party’s political campaign was launched 2 years later on Oct 2nd 2024. Bihar elections were conducted in the first half of Nov 2025. Prashant Kishor launched a padayatra to start this campaign covering over 3000 kms across the state. So, the campaign had close to 3 years to present itself to voters. Jan Suraaj Party got a vote share of 3.41% in Bihar assembly elections 2025.

Inadequacies in political communication

Generally, every election analysis can be summarized in a few factors concerning the main narratives (the communication part), the alliances, and the concrete benefits you can provide to people. We can consider the caste/religion/gender aspects to be included under communication as demography is generally part of the communication plans. While definitely the local cadre strength and party networks play their part, for the sake of this article, I would like to consider it not relevant for a new party like Jan Suraaj Party.

Communication is the most vital of all, because it directly talks to voters. If voters are impressed, it can improve the party’s negotiation for alliances at the time the election is close by, if required.

As Jan Suraaj Party did not keep any alliances towards the end, it means that it had no other option but to rely solely on communicating directly with voters. As it was not an incumbent party, it also had no option to demonstrate any direct concrete benefits to people like a pre-election DBT.

So, communication was the bedrock of JSP, if at all it had to make any impact, over and above the fact that it was a new entrant. In practice too, since the party relied heavily on central leadership and communication, it is only fair to comment about how strong the strengths are, rather than analyzing it based on how Prashant Kishor did not choose to play the game.

When you frame the debate as about “arsh par ya farsh par” (either high on sky or down on the ground), it was all about creating the tipping point where voters start tilting towards you. At the core of it was the ‘coordination problem’.

A new entrant’s ‘Coordination Problem’

A padyatra approach has the single biggest benefit of always being in news and occupying media space. Apart from connecting with local voters, every day is an opportunity to create news as the leader is among people. So, padyatra offers immense scope for communication at both local and state levels. However, while the platform and the person to communicate were present, it appears that the message to communicate wasn’t persuasive enough.

Prashant Kishor’s popularity as per surveys published before elections, on popular chief minister faces in Bihar, was among the leading popular faces, if we were to believe these surveys. However, many times, personal popularity does not translate to votes.

Coordination problem in game theory means that involved individuals (in this case, voters) do not take their best decision because they don’t trust the other voters to coordinate. Instead, they stick to traditional choices.

A case in point is the huge crowds for Pawan Kalyan in Andhra Pradesh where tens of thousands of people in many constituencies actually participated in his public meetings, while only a very few of them actually voted for his party in 2019.

Reasons people generally give to explain this phenomenon is that the supporters of Pawan Kalyan were minors without voting rights, or that the people just came to see him as he is a film star. However, this phenomenon is possible because the undecided voters, though they might look at the new leader favourably, actually do not vote because they believe the fellow voters are not going to vote for them – effectively making them believe the new leader is incapable of winning. This case is strengthened because of the earlier performance of Pawan Kalyan’s own brother, Chiranjeevi’s earlier electoral debacle in 2009. If Chiranjeevi himself could not form a government, Pawan Kalyan could not definitely have formed – thereby making their vote wasted.

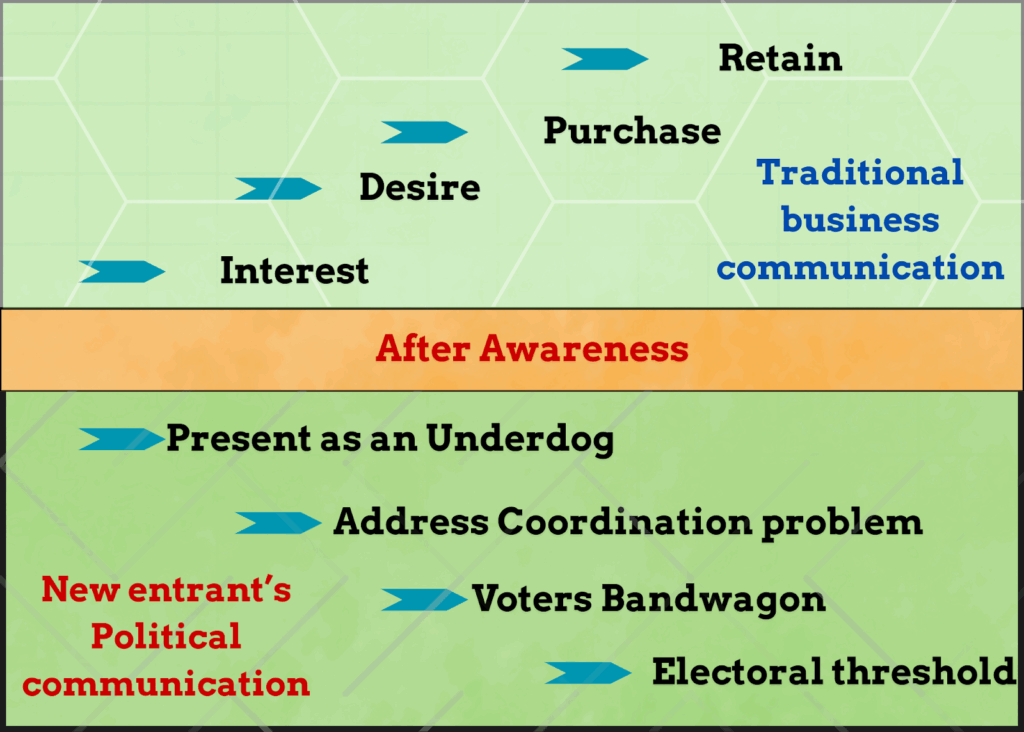

The perception that their vote becomes wasted, if the fellow voters do not vote for the new leader or if the fellow voters do not judge the new leader favourably means they stick to traditional choices. So, a big challenge for new entrants is to be able to address such perceptions when they know that they are reasonably popular.

The coordination problem is most effectively addressed when there are leaders who motivate individuals to make decisions by strengthening the individual’s will, rather than evaluating how others vote, or whether the leader has capacity to win.

Once the new leader addresses how to convert the votes of those supporters who look at him/her favourably, the next step is to move towards ‘bandwagon effect’ where even others who did not see the new leader as an option will start taking them seriously and find reasons to vote for them. An example of how a bandwagon effect is executed is when surveys are published in your favour in media channels. These favourable surveys give a reason for voters to take a decision as they want their vote to count and they exercise their vote to be on the winning side.

The following illustration shows a step-wise approach for the purpose of portraying different segments discussed above, though all of them could be parallelly acting many times.

For example, if credible surveys suggest that 15% of voters see you as a popular CM face, the next step is to ensure that a good part of these 15% actually vote for you. This can be achieved by addressing the coordination problem in these 15% voters by providing stronger reasons for them to vote for you. The next step is to convert/direct these 15% supporters towards becoming 25% supporters by creating a bandwagon effect through publishing surveys, increasing the communication reach of your messaging, testimonials, etc. Once there is a reasonable share of voters seriously considering voting for you, alliances in the final stages can help you cross the electoral thresholds you require to capture power.

If we hold that the voter behavior is mouldable beyond traditional party loyalties, or social identities like caste, gender, or religion, coordination problem is always a practical situation to address for all new leaders. In Prashant Kishor’s own words, close to 60% of Bihar’s voters wanted change – suggesting that the Bihar voter was probably mouldable.

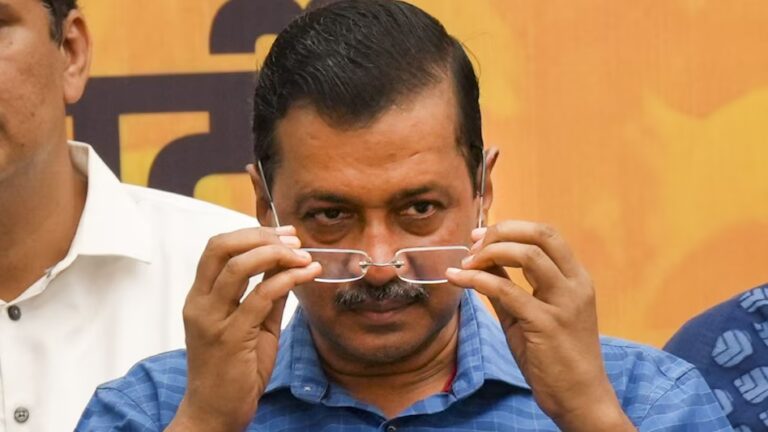

Kejriwal and the ‘Coordination Problem’

The most recent successful political entrant in India has been Arvind Kejriwal. On the back of the India Against Corruption (IAC) movement, Arvind Kejriwal rose to power in Delhi in 2013.

While Kejriwal’s success is generally discounted as being in an urban area, or stealing credit from the IAC movement, Kejriwal also demonstrated success that no one else has seen since then. Kejriwal’s success in 2013 is a case to discuss the ‘coordination problem’ because he provided voters with more reasons to vote, over and above holding a favourable opinion towards him.

Whether it is the contest against Narendra Modi in Varanasi, or Sheila Dixit in Delhi, Kejriwal had shown that he was bigger than what people could have perceived for a new entrant, by anchoring himself with leaders of larger size. Recently, this was also observed by a relatively smaller leader, Revanth Reddy’s contest against an incumbent chief minister, KCR, in Telangana.

Kejriwal gave two stronger reasons for voters to vote in 2013. One, he made himself look bigger than a general new entrant as he contested against the leading power figures of his times. This could make the voters perceive that this person is not insignificant for their vote to go to waste. Second, he made his supporters feel their vote mattered more, as his challenges are now difficult as his opponents are bigger people. So, they had to transfer their vote towards him, against the bigger powers and that their decision had value.

Kejriwal initially won 28 seats in his party’s debut in 2013 Delhi elections. He then called for a re-election to get larger support as voters are now more confident of joining the bandwagon to support him to form the government. This time, he got 67/70 seats in 2015, most possible as people wanted to join the ‘band wagon effect’ to be part of the winning side.

Interestingly, the recent claim by another new entrant, the popular movie star, Vijay under the TVK banner in Tamil Nadu that there were just two parties (DMK and TVK) in Tamil Nadu for this election is a way of saying that their vote for ADMK will get wasted. This line will lead to a ‘coordination problem’ among ADMK voters. If executed well with steps like poaching ADMK leaders into TVK, testimonials that suggest people transferring support from ADMK to TVK, etc., if a coordination problem is successfully created in Tamil Nadu, it reduces the leverage of ADMK in the coming elections, whether to contest alone, or to oppose Vijay as a CM face in case of an alliance led by TVK. This is always a good line for the TVK to pursue, as it has definite benefits.

To contest against the incumbent power center is always an opportunity for new entrants. While the new entrants may lose in that particular constituency, it can reap benefits in the overall performance of the party, as it makes the party relevant for people to consider while voting.

In the case of Jan Suraaj, the new entrant has not even contested the election, far from contesting against the biggest leaders of his state. This even makes the leader smaller than what they actually are, as it demonstrates a lack of political will.

Prashant Kishor gave an absurd reason that he could not campaign in the state if he focussed on his own constituency. This was probably the best opportunity he had to solidify his political relevance among voters. In case he actually contested, the vote share of Jan Suraaj Party could have been higher. In case he contested against the incumbent power centers he challenged, it could have been further higher. But the party ended up with a 3.41% vote share in contested seats.

The post election press conference by JSP leaders also highlights that people transferred their votes from JSP to NDA as they wanted to avoid a ‘Jungle Raaj’ under RJD again. This explanation only reflects the inability to address the coordination problem beforehand, and even deepening it further by Prashant Kishor’s decision of not contesting in the election.

Missing political conviction: Symptom of a larger problem?

An interesting feature of Jan Suraaj’s communication is an element of disinterestedness in political power. The construction of a social image for the party as an ‘andolan’ instead of providing a rationale to justify political power for social change could either be strategic with a long-term point of view, or a result of a personal elitist dilemma.

Another case in point is that of Loksatta Movement, led by a former bureaucrat Mr. Jayaprakash Narayan. Emphasis on idealism and ethics in politics, Loksatta Movement prides itself in being social since a long time before it took plunge into politics, after its leader announced stepping away after an electoral defeat. Loksatta continues to be a socio-political organization without a pursued focus on electoral politics. Jan Suraaj Party’s performance in Bihar is only slightly better than Lok Satta Party’s performance in combined Andhra Pradesh in 2009 with 2.04% vote share in the state.

It is possible that new entrants to politics also struggle to express a strong political rationale for their entry. This is probably because of the perception of selfishness associated with clinging to political power. This personal skepticism or mental dilemma towards judging themselves as selfish probably makes new entrants distance themselves from directly seeking political power for social change. In creating this distance, they also risk becoming elitist as they don’t want to ask for something as most new entrants perceive themselves to be doing a sacrifice, or leaving their personal luxuries to change society. The dilemma that they don’t want anything but they want political power makes it a bit tricky. If at all, they have only given up something they should have wanted.

Above this tendency to be selfless, technocrats with an inflated sense of achievement find it more challenging to ask something from the least fortunate in society. The electoral process demands that leaders have the capability to be humble. In seeking votes, is also an element where the new entrants realise that they need something that others possess. But when they perceive themselves highly, this humility may not come naturally to them. So, instead, they choose to expect or want people to realize their greatness and vote for them, rather than actually asking for something from people. They appeal to larger neutral ideals, to cleanse themselves of any personal vested interests.

This personality trait of perceiving themselves as above others could force them to adopt a more sanitized approach to how they perceive their pitch for political power even if their passion for social change is genuine, rather than taking a more direct entrepreneurial approach to own their political relevance. Hence, a social selfless mode is preferred when one is concerned about ‘wanting’ something to do social good.

Another form of technocrats, most bureaucrats fail in Indian politics, most probably because they were used all their lives to be respected by their office staff, or citizens who plead for their attention. They do not earn their worth by the virtue of their leadership, but by their bureaucratic authority. All of a sudden, if they have to ask something from those who always respected them, it is an existential nightmare for their personal worth. So, they expect common people to realize their achievements and entrust them with power.

This personality trait also affects how one leads. Especially, in democratic politics, leaders have to deal with people with differences and people who are themselves leaders in their own way. An inflated sense of oneself can make it distant to have a strong political justification for one’s social role. This could fundamentally affect how one sees a political outfit, thereby reducing its focus for electoral success, even when it is desired.

Way Forward: Avoiding the Self-Serving Bias

While it could have been a welcome change to see new entrants into Indian politics, it appears that Jan Suraaj failed both on the front of leadership as well as strategy.

Whether it is Arnab Goswami’s warning packaged as an advice, or Rajdeep Sardesai’s mocking modelled as reporting, the world wanted India’s foremost strategic advisor to be humbler. The new politician probably needs a leadership consultant as much as a strategy consultant.

Voters definitely do not make the best choice all the time. But if you were ready to accept their verdict when it was in your favour, you should be ready to accept it even when it is not. Self-serving bias is when you credit yourself for your successes, while you blame external factors for your failure.

This framing of their political presence as an opportunity for people to reform themselves, rather than seeking an opportunity from the people to change things is visible in Jan Suraaj’s X (twitter), after its loss, which reminds us of Prashant Kishor’s earlier speeches of advising people on whom to vote for, or why it is important to vote for good people. A self-serving bias is inbuilt in such a framing. A self serving bias does no good, than diverting leaders from their political missions. Only when the verdict of people is upheld, can accountability be placed on leaders to remind them of their political mission, rather than feeding their self-serving bias to feel great about themselves. It is important for new entrants to overcome this self-serving bias, in order for them to actually move towards change.

A party with Gandhian ideals need not be reminded of Gandhi’s popular quote:

“First, they ignore you;

Then, they laugh at you;

Then, they fight you;

Then, you win!”

Featured Image Credits: Financial Express