Manmohan Singh, PV Narasimha Rao, and times that mattered

Shanmukha was a managing editor at the journal

What happened before the 1991 reforms?

It was 1969, and the Secretary-General of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) had just promoted a brilliant economist. But he was in for a rude shock when he saw that the newly promoted economist had just resigned after he felt his place belonged to his country. All the Secretary-General could tell him was, “Well, maybe you are right. Sometimes the wisest thing to do is to act very foolishly!” And thus, Dr. Manmohan Singh made his way back to India, to teach economics. His ideas and research caught the imagination of the Shri Haksar, who headed Indira Gandhi’s secretariat, and that led to his induction into the public administration, where he held positions like the Chief Economic Advisor and RBI Governor. Yet, Dr. Manmohan Singh’s entry into politics was rather dramatic.

PV Narasimha Rao was seriously contemplating retiring from active politics in 1991, and with the gruesome murder of Rajiv Gandhi, he was tasked with steering the Congress government. But why PV Narasimha Rao? He was not the first option; the then Vice-President Shankar Dayal Sharma was. But, Shankar Dayal Sharma politely declined the offer, and they turned to PV Narasimha Rao, a loyal Gandhi family supporter, with decades of political experience and acumen behind him. He had guided Rajiv Gandhi on various aspects of governance, was a close confidante of the Gandhi family, was respected and revered, and maintained cordial relations with the top brass of the Congress leadership always. Moreover, this was a chaotic moment for India.

“The darkest hour is always before the sunrise,” someone told. Probably this was India’s darkest hour after independence. India was reeling from high unemployment rates, a rapidly falling economic growth rate, changing leadership, and drying up of foreign exchange reserves running the risk of defaulting loan payments. And it was amidst this, that PV Narasimha Rao took charge as the Prime Minister of India. Once the leadership began to stabilize, he turned his focus towards economic stabilization.

The history of the Economic mess

For the first time in 18 years, India has posted a trade surplus for the month of June 2020. This meant that India exported more than it imported. But this was not the case in the lead up to 1991. And like many others say, “There was 1966 before 1991”. In a sense, the first whiffs of economic liberalization were to be felt in 1966 under the leadership of Indira Gandhi. India was experiencing serious hiccups in relation to an increasing trade deficit it was notching up. Since India was a relatively young nation that was still categorized as under-developed or least developed by the IMF, with an ever-increasing trade deficit and a big loan book, countries were beginning to impose tighter import regulations on India, as a result of declining confidence. Lower imports mean a lesser number of imported items going up for sale in India, and if the demand were to remain the same, the prices would increase, right. This phenomenon is called Inflation; when the prices of objects are higher than their intrinsic worth, due to lower availability in the free market. During this time, India’s food inflation was at 20%. The food crisis was to become more severe before it triggered the Green Revolution much later. But, during this time, the gap between imports and exports was rising.

So, in 1966, a committee set up, tasked with initiating reforms to pull India out of this crisis, led by a World Bank economist, suggested reducing the licensing system for industries in India, apart from many others. These included lowering the role of the public sector and giving the private sector more prominence. In hindsight, the most decisive recommendation of this committee was the devaluation of the Indian rupee to boost exports. What is devaluation, and how could it be the antidote to the economic crisis?

To explain this better, let me illustrate. Let’s assume that a dollar is equal to a rupee. A car being manufactured in India that costs Rs. 500,000 would also be $500,000 at this rate. During devaluation, the value of Indian rupee reduces. If Indian rupee were to be devalued by half in this example, it would mean that, while we Indians would pay the same 500,000 for this car, the US would pay us just $ 250,000 lakhs. So, it just got cheaper and much more attractive to other countries. They would demand more, and this would encourage our traders to export more. Couple this with costlier imports for us. For an object that we paid Rs. 100 previously, we would have to shell out Rs. 200 after the devaluation. So, we would now import less as it’s costlier. As we export more and import less, we could slowly offset the trade imbalances in a few years, hoping everything else remains constant. While this is theoretical, the implications from real-world applications are manifold.

In the real world, this did not pan out the way it was intended to. The Indian rupee was devalued by more than 35%; it went from Rs. 4.76 to Rs. 7.50 to 1 dollar. Coupled with this, the Defence sector’s allocation increased by 100% (remember there was India – Pakistan in 1965, leading to The Tashkent Declaration), and the Indian rural dried up as a severe drought scorched up the land.

What were the consequences?

The move was a massive disaster. It was one blow after another. This put an end to India’s ambitions to slowly open up the economy and liberalize. Coming back to power in the subsequent elections of 1967, this economic failure led Indira Gandhi to get back to controlling the market entirely. She nationalized banks, oil, coal, and introduced legislation and regulations that left foreign companies in India at a loss. Companies such as Coca Cola, IBM, and many more were forced to leave the country for good as India was going full steam in a bid to pump up its foreign exchange reserves and bring the economy back on track.

There were signs of India opening up again, under the leadership of Rajiv Gandhi. But it was being done slowly and very cautiously. The Indian economy was still growing at a slow pace; it was infamously called the ‘Hindu rate of Growth,’ mocking India’s economic situation. Rajiv Gandhi began to introduce ‘pro-business’ reforms, yet what India needed were not just ‘pro-business’ reforms but also ‘pro-market’ reforms. And this is exactly what PV Narasimha Rao and his freshly appointed finance minister Dr. Manmohan Singh identified – the need for ‘pro-market reforms.’ What is the difference, and why was it necessary?

What happened in the 1991 reforms?

In 1991, India had amassed loans to the tune of $72 billion, the third-highest in the world. We were dangerously close to being sucked into a vicious loan cycle. We were just short of getting declared bankrupt; it was said only a billion dollars lay in between. And PV Narasimha Rao, who took charge during this period, realized the need for a smart economist to head the Finance ministry. He picked up Dr. Manmohan Singh to become the finance minister and pulled out from obscurity, another brilliant economist, Pranab Mukherjee, who was appointed as the Deputy Chairperson of the Planning Commission. And they were on a fire-fighting mission to pull India back from the ‘brink.’ While there were many similarities that the lead up to 1991 has with the 1966 crisis, there were many other unique factors that built up.

How did 1991 happen?

While the problem of Balance of Payments was already solved with the rupee devaluation in 1966, what re-created this problem in the 1980s was the breach of contract in several of our rupee agreements with many countries. The erstwhile Soviet Union was a major trade partner, and we traded with them in rupees, which were a part of the agreements with this friendly nation. With the break up of the Soviet block into smaller countries, and also the formation of many other European countries led these agreements being dissolved.

1990 was also a pivotal year in global diplomacy. The Iraq – Kuwait tensions broke out into a full-fledged ‘Gulf Crisis.’ India depended on these countries for a bulk of the oil requirements, and the gulf crisis led to a drastic rise in prices, choking Indian finances. In a matter of 5 months, July 1990 to October 1990, the prices per barrel shot up from $15 to $35. To finance some of the payments, the government air-lifted 20 tonnes of gold to Zurich to receive a credit to the tune of a quarter billion dollars.

While all of these symptoms of economic illness did not manifest over-night, they were identified well in advance, but sufficient action could not be taken due to an on-going political crisis. The coalition government that was formed in 1989 saw 2 Prime Ministers; VP Singh and Chandrashekhar, in less than 2 years, by when India went to elections in mid-1991. During the elections, the Prime Ministerial face, Rajiv Gandhi, was murdered.

All of this led to a loss of confidence in India as a hub of business. This, along with a severe downgrading of India’s credit ratings by all credit rating agencies, led to foreign investors, NRIs, institutional investors, and others to pull their money out of the country.

Similar to 1966, countries began to impose import restrictions, and inflation began to jump. It was amidst all of this that PV Narasimha Rao and Dr. Manmohan Singh took over. In an interview with NDTV, Manmohan Singh said that he had propagated the idea of a measured liberalization and globalization of the Indian economy to Indira Gandhi in 1972 itself. Fate had other plans for him probably, for 20 years later, he had the opportunity to put his ideas into action.

The accidental Finance Minister

In a speech during the launch of his book “Changing India” in 2018, Dr. Manmohan Singh said that he was not just ‘The Accidental Prime Minister’ but also ‘The Accidental Finance Minister.’ Manmohan Singh, whose responsibilities were limited to the administration, entered the arena of politics all of sudden. He was heading the UGC (University Grants Commission) when he received a phone call from PV Narasimha Rao. Manmohan Singh had already received the PM’s advisor at his home the previous day and did not take seriously what was offered. The Prime Minister asked him to get ready and present himself for his swearing-in ceremony, which was a few hours away.

Curing the malady

What India needed at this point were not just financial reforms, but a comprehensive package, including a trade and industrial reforms to revive. And they were done. Before the new reforms were introduced, the Finance Minister and Prime Minister, in consultation with the then RBI Governor S Venkitaraman and his deputy C Rangarajan decided to devalue the rupee two times. The first, a minor devaluation, done on July 1st, was done by 9%, which was meant to perceive the political and public reaction. The second, which was scheduled for 5th July, Dr. Manmohan Singh said, almost did not happen, owing to the negative reaction from all, forcing the PM to seriously reconsider. The Prime Minister was adamant. He asked Dr. Singh to instruct the RBI to hold the second devaluation. However, by the time the call was placed to RBI, the devaluation was done.

Next up, P Chidambaram, the Minister of State for Commerce, announced the New Trade Policy (NTP) to simplify the regulations to import or export goods and encourage trade. This was followed by industrial reforms unveiled by PJ Kurien, the then Minister of State for Industries. It reduced the need to obtain industrial licenses to just 18 industry sectors, freeing up almost three-fourths industries from this back-breaking framework. The private sector was opened up and allowed to take on more responsibility, making the process of conducting business a little simpler at the same time.

The dawn of an Idea

The Finance Minister, Dr. Manmohan Singh, in a historic speech, launched the New Economic Policy, which opened the liberalized India ready to take on the world. There has been no looking back since then. India has grown leaps and bounds; went from the ‘Hindu rate of growth’ to ‘Tiger growth’ in reference to the Tiger economies, that witnessed rapid development, before India. Companies which had left India in the 1970s began to make a beeline to open up their businesses. Coca Cola jumped in almost immediately, and others followed suit. With more than $516 billion, India now boasts one of the world’s highest foreign exchange reserves. As India began to open up public sector companies that were established by Nehru to the private sector, leading to heavy criticism, it also led to better products within reach of the common person.

As the industries carefully nurtured by Nehru and his ideas of industrialization, which were slowly built up till then, were being privatized, many felt it would lead to the Indian market’s death. However, as Dr. Manmohan Singh said, what was created by Nehru and nurtured for those many years were absolutely critical for India to take full advantage of the 1991 reforms. The resilience and industrial-strength built, though not sufficient, helped India stand strong with the sudden flood of foreign players. After the term, PV Narasimha Rao was expelled from the party for having brought in serious changes in the way Congress functioned as a party; and the Congress deliberately discredited him for the success and economic turnaround achieved under his leadership. Manmohan Singh, for his unflinching loyalty to the Gandhi family, became India’s Prime Minister for a decade, and Congress attributed the success of the 1991 reforms solely to him to create an appealing image for the voters.

Every coin has two sides. Every decision has both positive and negative effects. What we need to understand is what outweighs the other. What about the 1991 reforms? Has it been a success? Has it achieved the intended outcomes? Has it been detrimental to India as a whole?

What happened after the 1991 reforms?

We have all been the recipients of the boons of the ‘91 reforms. India has seen an economic boom. The ‘91 reforms were an economic success, but that wasn’t the only aim. It definitely rescued India from the emergency that presented itself at that point. But did it create a ‘Frankenstein’ of manifold proportions that we are failing to wrestle and tame now? Though the decisions taken were measures to cure the economy, their results were not limited to that alone. If the flapping of a butterfly’s wings could turn up a storm on the opposite side of the world, these decisions would certainly have effects beyond imagination. Anyways, as I have already talked about its necessity and its many positives in the preceding article, I’ll try to list down some of its drawbacks.

Did something go wrong?

In this report by Oxfam India, the author Prof Himanshu from JNU writes, “What is particularly worrying in India’s case is that economic inequality is being added to a society that is already fractured along the lines of caste, religion, region, and gender.” The 91 reforms have not only added to the existing problem of economic inequality but also have accelerated the growing divide, sadly, with the deserved benefits not having trickled down to the real beneficiaries.

The trickling down effect! The economic policies that were introduced benefitted the industries, and it was the responsibility of these respective corporate beneficiaries to pass on these benefits. One way to explain this is through the changes in the minimum wage rates. For the 1st time, in 1948, the Indian government defined a minimum wage rate that was to be followed by every employer in the country. The aim of this minimum wage rate was to ensure that such an income rate would secure a basic standard of living for the worker; in terms of food, health, accommodation, education, and any contingency. In 1991, the minimum wage rate was Rs. 35.4, which increased to just Rs. 178 by the end of 2020, an increase of 5 times. Compare that to the 10 times increase in the GDP, from 27 thousand crores to 290 thousand crores. Their utility to the economy has increased, but their due from the economy has risen not equally. What is the use of increasing the minimum wage rates when the necessary steps to enforce them are not being done properly? It reflects poorly when 33% of all employees or 62 million workers are paid less than these limits, as per this report by the International Labour Organisation.

Another example of how these benefits could be passed down is through the formalization of labor and employee wage rates. Many organizations and companies continue to engage heavily in contractual and informal labor, despite being excessively dependent on them. If they were to be formalized, the employers would be expected to follow the Indian wage rates, and the workers would be eligible for many of the salary requisites like provident fund, life&medical insurance, and a dozen other allowances. It is sad that after all these decades of liberalization and privatization, more than three-fourths of the Indian economy are still in the informal sector.

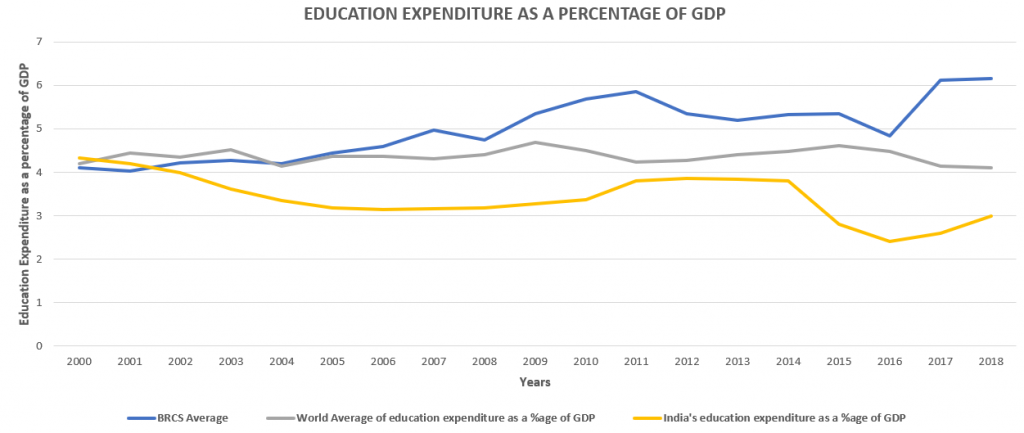

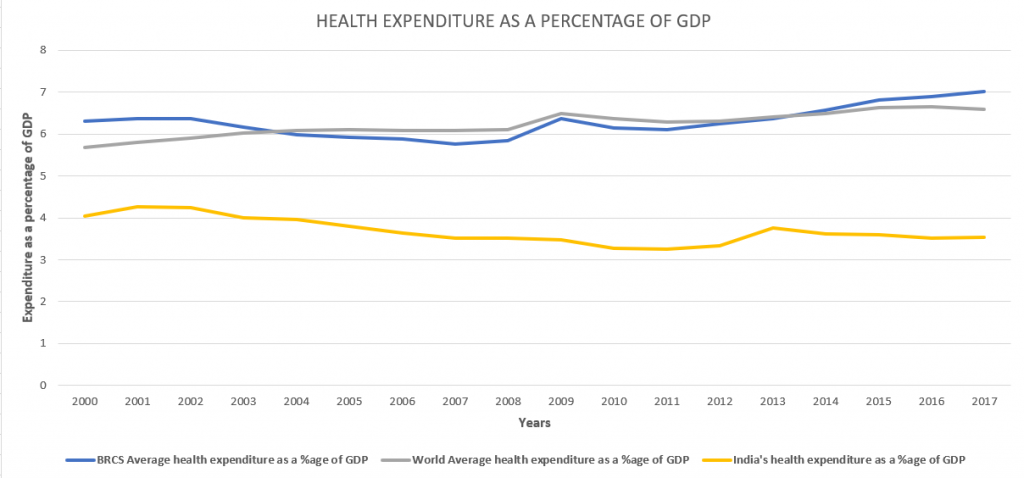

India might have sprinted in the growth race and is probably catching up with many of the world’s fast-developing economies. At the same time, we have lagged consistently in the Human Development Indices. Rising economic growth offers not just an increasing income amongst workers but also a higher budget at the disposal of the government to spend. While the incomes have not registered a respectable growth, what about the public services that the government is responsible for, into which it pours crores of rupees every single year; into education, healthcare, food, etc. The allocation of these fundamental public services has remained abysmally low. Datasets from the freely available databank of the World Bank group highlight these facts. India’s spending in the education sector, as shown in these charts has been lower in comparison to the rest of the world and especially in comparison with the BRICS nations (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa), countries with similar growth rates and economic stories. The same is the case with the healthcare sector.

While we have constantly tried to better ourselves and others in terms of ‘Ease of doing business,’ making it convenient for foreign companies to set up their presence in India, we’ve not tried to do the same for basic necessities like health, education and many others or ‘Ease of living.’ This can be proved from the fact that India is at 63rd position in ‘Ease of doing business’ while languishing at 129th rank in HDI (Human Development Indicators). The focus all through this golden period of growth after the 1991 reforms has continued to help businesses and the already privileged flourish, while the poor and needy continue to struggle for just living.

Bettering our ease of doing business is definitely not a mistake. But attaching equal importance to the groups at the bottom of the ladder is also much needed, and that is what has been avoided for long, probably. In their brilliant book, “An Uncertain Glory,” celebrated authors and economists, Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze, write, “Growth alone is unlikely to end these problems, at least not within a reasonable time frame, but it is certainly much easier to remedy such deficiencies in a growing economy.” An absolute treat to every mind curious, this book lays out the Indian economy in honest nakedness.

Simply put, I feel that these reforms and the adopted paths have helped pizzas and burgers reach the Indian shores rather than ensuring that basic food grains reach the mouths of the hungry poor. It helped the privileged Indian relish Pepsi and Coke, while the common Indian struggled to access potable drink that could be consumed. I have enjoyed all of these guilty pleasures myself, but traveling to the ground and seeing for myself how the benefits have trickled down has been a changing experience. I was born and grew up in rural India, but could not really comprehend and compare these economic differences until I reached Delhi to study post-graduation. It changed me. The story of that is for another day, though.

Bibliography:

- To the Brink and Back: India’s 1991 Story; Jairam Ramesh. September 2015.

- An Uncertain Glory: India and its contradictions; Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze.

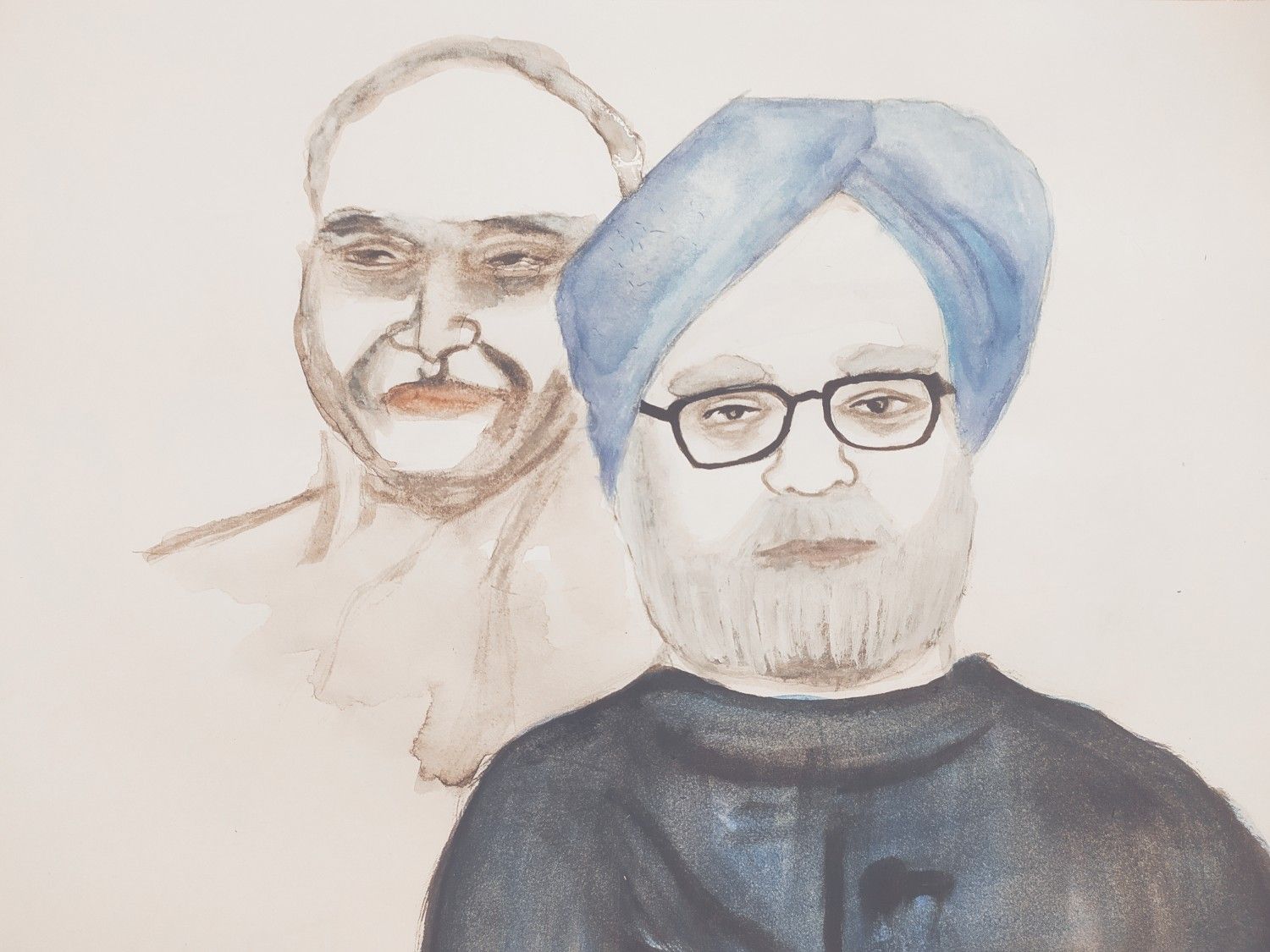

Featured Image Credits: Flickr

Good yarr

The way Indian economy was affected by Indian politics is well portrayed. I agree with you that the 1991 economic reforms did not bring the intended change. Thank you Shanmukha for bringing out such a interesting and enriching article.