India after Independence: A New and Divided Nation

India gained independence in August 1947 and immediately faced enormous challenges. Partition brought 8 million refugees from what is now Pakistan. These people needed food and work. Then there were the princely states, controlled by maharajas or nawabs, who had to be convinced to join the new nation. Refugees and princely nations’ concerns must be addressed quickly. Ultimately, the new nation needed to build a government that met its inhabitants’ goals and aspirations.

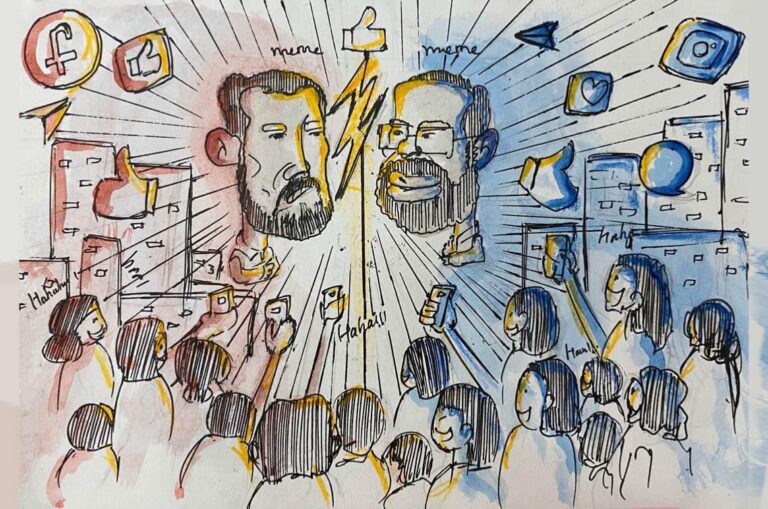

In 1947, India had a population of 345 million. It was split. The high and lower castes, as well as the dominant Hindu population and other religious Indians, were divided. A wide diversity of languages, fashions, cuisines, and occupations were spoken in this large territory. How could they be forced to live in harmony inside one nation?

The development issue was added to the unity issue. During independence, most Indians lived in villages. Farmers and peasants relied on rain. If crops failed, barbers, carpenters, weavers, and other service providers were underpaid. Factory workers lived in slums with little access to education and healthcare. Clearly, more agricultural output and new job-creating enterprises were required to pull the fledgling nation’s inhabitants out of poverty.

We needed both. If India’s divides are not addressed, violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims, for example, may erupt. Conversely, if economic development does not benefit the majority, it may increase existing disparities – such as between the affluent and the poor, urban and rural areas, and India’s prosperous and laggard regions.

A Constitution is Written

Between December 1946 and November 1949, about 300 Indians met to discuss the country’s political destiny. The “Constituent Assembly” met in New Delhi, despite the fact that representatives came from all over India and political parties. The Indian Constitution was adopted on January 26, 1950.

The Constitution established universal adult franchise. All Indians over 21 can vote in state and national elections. Indians have never before been empowered to pick their own leaders. Other countries, including the UK and the US, gave this freedom gradually. Initially, only males with property could vote. Then came educated men. Working-class males gained the right to vote after a long fight. Women acquired the right to vote in the US and the UK after a long fight. However, India opted to grant this right to all people immediately after independence, regardless of gender, class, or education.

The Constitution also promised all people equality before the law, regardless of caste or religion. Some Indians wanted for a Hindu-based administration and for India to be run as a Hindu state. On one hand, Pakistan was created to protect and advance the interests of a certain religious community, Muslims. However, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru believed India could not and should not become a “Hindu Pakistan.”

Aside from Muslims, India has large Sikh and Christian populations, as well as Parsi and Jains. They would enjoy the same rights as Hindus under the new Constitution, including equal access to government and private sector jobs and legal protections.

Third, the Constitution benefited the poorest and most vulnerable Indians. “Slur and stain on India’s rightful name” was untouchability. Previously only accessible to the wealthy, Hindu temples now welcome everybody. After much discussion, the Constituent Assembly proposed a specific number of parliamentary seats and government posts for people of the lowest castes. Some claim that Untouchable (Harijan) candidates did not score high enough to be accepted into the renowned Indian Administrative Service. According to H.J. Khandekar, a member of the Constituent Assembly, the higher castes were responsible for the Harijans’ “current unfitness.” Khandekar said to his more fortunate colleagues:

The Scheduled Tribes, like the previous Untouchables, had seat and position reservations. These Indians, like the Scheduled Castes, were denied and discriminated. People were denied modern healthcare and education while foreigners seized their lands and woods. In the Constitution’s increased rights, this was compensated.

The Constituent Assembly debated the central government’s authority vs. state governments for days. Some members believe the Centre’s interests should come first. Only a strong Centre could “think and prepare for the country’s total well-being,” it was maintained. Others felt provinces should have more power and autonomy. Mysore member expressed concern that “democracy is concentrated in Delhi and not allowed to work in the same meaning and spirit throughout the country.” In the words of a Madras member, “provincial governments should have main responsibility for the wellbeing of their people.”

For example, taxes, defence, and foreign affairs would be solely the responsibility of the Centre; education and health would be primarily the responsibility of the states.

Language was another hot topic in the Constituent Assembly. Many members felt the English language, along with the British, should be eliminated from India. They suggested Hindi in its place. Those who did not speak Hindi had a different perspective. T.T. Krishnamachari warned the Assembly on behalf of the South’s people, some of whom threatened to leave India if Hindi was enforced. To resolve the issue, the government agreed to utilise English in courts, government operations, and inter-state communications.

Many Indians helped draught the Constitution. Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, who led the Drafting Committee and oversaw the document’s finalisation, made the most significant contribution. Dr. Ambedkar emphasised economic and social democracy in his farewell address to the Constituent Assembly. Allowing individuals to vote would not eliminate other inequities, such as wealth disparity or caste disparity. He predicted that India’s new Constitution will bring contradictions. We shall have equality in politics, but disparity in social and economic life. We shall recognise one person, one vote, and one value in politics. Because of our social and economic system, we will continue to reject the concept of one person, one worth.

The Nation, Seventy Five Years on

In August 2021, India will begin a year-long celebration of 75 years of independence, with programmes and initiatives highlighting “development, governance, technology, reform, progress, and policy.” The Prime Minister’s Office has begun a detailed planning process for the 75th anniversary of Indian Independence. Prime Minister from Red Fort is expected to kick off the year-long spectacular celebrations on August 15, 2021. In order to highlight India’s “development, governance, technology reforms, progress and policy”, all federal ministries and departments were invited to pick ten projects.

Among the initiatives on the table are energy efficient street lighting, command and control centres in all 100 smart cities, garbage-free 2,022 cities, and migrant worker skilling. The ministries have planned projects to be finished by August 2022 and launched by Modi. In its 75th year, the Smart City Mission has selected 163 projects totaling Rs 20,404 crore. The Swachh Bharat Mission plans to declare 2,022 cities ODF++ by 2022.

There will also be a Global Tech Festival to highlight all technologies utilised in India, lake restoration projects, river front development, smart schools, and digital libraries.

The culture ministry will coordinate activities at India Gate, special marathons, and cultural nights in cities that fought for India’s independence. One possibility is a special session of parliament at the newly built Parliament building. The ultimate plan determines. “The new Parliament building should be finished by August 2022,” a senior source engaged in the planning discussions told ET. “Sure, the winter session will be there. There may be a special session first.”

India will mark 75 years of independence. How has the country fared? And how well has it lived up to its founding ideals?

We may be proud of India’s continued unity and democracy. Many foreign commentators believed India would not be able to exist as a single nation, and that each area or linguistic group would want to create its own nation. Others predicted military control. Since Independence, there have been thirteen general elections and hundreds of state and local elections. A free press and an independent judiciary exist. Finally, diverse languages and beliefs have not hindered national unity.

However, significant divides exist. Despite constitutional protections, the Dalits, or Untouchables, endure violence and prejudice. Many rural Indians are denied access to water, temples, parks, and other public sites. Despite the Constitution’s secular principles, religious organisations have clashed in numerous states. Above all, as many analysts have noticed, the wealth gap has widened. Economic progress has benefitted some areas of India and some Indians. They own big mansions, eat at costly restaurants, send their kids to pricey private schools, and travel abroad frequently. Meanwhile, many more remain poor. They can’t afford to send their kids to school because they live in slums or in rural villages on poor land.

Equality before the law is recognised in the Constitution, but not in reality. The Republic of India has not been a tremendous success by its own standards. But it hasn’t been a success.

References

- Chandra, B. (2016). India’s Struggle for Independence: 1857 to 1947, Penguin Random House India, Penguin India.

- Bansal, S. (2018). Post-Independence India, McGraw Hill Education.

- Kulkarni, A. (2021). Post-Independence India: Consolidation and Reorganisation, Oak Bridge Publications.

Disclaimer: I certify that this is my original piece of writing neither published nor in the consideration of any publication. This is exclusive to “The ArmChair Journal.”