Freedom at Midnight: Revisiting Gandhi and his vision of India

Dr Sipoy Sarveswar teaches Anthropology at University of Hyderabad. He writes on political and cultural issues in South Asia.

One of my friends referred to the book Freedom at Midnight by Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre for me to read. I also thought it is a good idea to read the book, especially when we are nearing yet another anniversary of India’s freedom from British colonial rule. While I was at it, one of my students expressed her opinion about the book, that it is more of a tribute to Lord Mountbatten- the last Viceroy of British India and First Governor-General of Free India. I also felt, she was right, and authors seem to focus on India and its masses, especially from the ‘western supremacy’ and illustrate the conditions that prevailed at that time with a hint of racism.

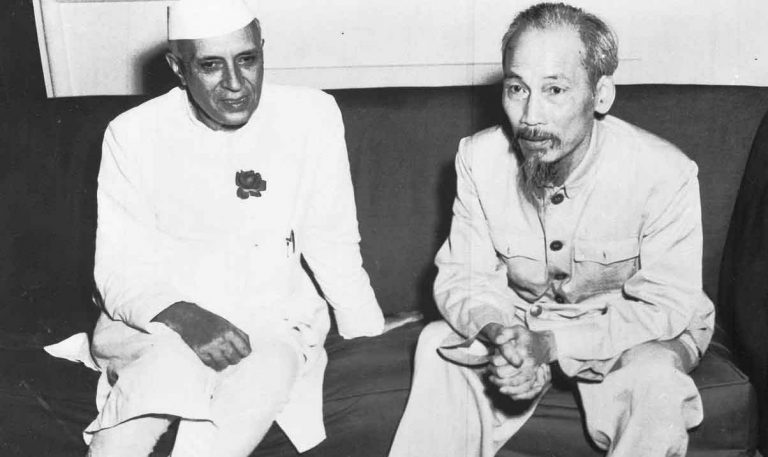

However, I asked myself, will it be justifiable for me to write otherwise, the contrary to what their research suggests? Definitely not. The book was captivating for one particular reason- the details are provided as anecdotes for the readers to understand the situation better. The book justifiably discusses the four main characters at the time of British departure from the Indian subcontinent- Mountbatten, Gandhi, Nehru, and Jinnah.

This book also serves as an important source to revisit Gandhi to understand his principle of non-violence, his commitment to his philosophy, and his vision of India. It would be a tribute to the ‘great soul’ to recall what he stood and died for, especially in the changing political scenario of the nation.

The book introduces Gandhi- 77-year-old man ‘who had done more to topple the British Empire than any man alive,’ from his visits to take his non-violence philosophy to the communal riots affected Srirampur, Noakhali of Bengal in January 1947. He was there to preach non-violence and offer himself for the mobs that are killing each other based on religion. This is a frenzy of communal hatred fanned by the Jinnah’s Direct Action Day call on 16th August 1946. The ‘Moslem League’ leader Jinnah employed the direct action day to pressure the Congress and the British to agree for his demand for a separate country for the Muslims- Pakistan. The idea of Pakistan was formulated by Rahamat Ali, which was rejected as an impossible dream by Jinnah but later came to own the idea and succeed in pressurizing the Congress and British to divide the subcontinent into two, through extreme violence. When Mountbatten suggested, he does not see another option, but to partition India, the apostle of nonviolence-Gandhi remarked ‘over my dead body. So long as I am alive. I will never agree to the partition of India’. One day one of the villagers unable to understand what Gandhi was doing in Noakhali instead of negotiating with Jinnah and the Moslem League remonstrated with him for wasting his time.

‘A leader,’ Gandhi replied, ‘is only a reflection of the people he leads.’ The people had first to be lead to make peace among themselves. Then, he said ‘their desire to live together in peaceful neighbourliness will be reflected by their leaders’

With the pressure to depart from India at the earliest and the Jinnah’s insistence on having a separate nation for the Muslims and feeling dejected to convince his disciples about his alternative plan, Gandhi was not only heard, but his beloved country was to be subjected to partition. Gandhi, fearing his actions and words might lead to the eruption of communal riot had to concede his defeat.

With Jinnah threatening violence and the ‘destruction of India,’ the leaders had to agree for the partition plan. However, the real problem and the aftermath of partition-the largest exodus and violence the world witnessed, resulted from a lack of careful planning and time given to the people to accept their new reality. Mountbatten being in-charge mustered his two great armies- one with 55,000 troops and one with Gandhi and sent them to Punjab and Bengal, respectively. Gandhi agreed to go to Bengal and try to prevent the communal violence upon the request of Mountbatten and also another Muslim leader-Suhrawardy from Bengal, who had actively mobilized Muslims against Hindus during the Direct action day. The Hindus of the Bengal felt Gandhi was trying to protect Muslims and rebuked him ‘go save Hindus in Noakhali,’ ‘save Hindus, not Moslems,’ and ‘traitor of the Hindus.’ Gandhi replied, he had assurance from the Muslim leaders that not even single Hindu will be harmed, and if they did, he would take up fast unto death. He also stated, ‘you wish to do me ill, and so I am coming to you.’

Unable to understand the untethered commitment to his principle and willingness to risk his own life to save the people from killing each other, the people of Bengal have succumbed to his magic and laid their weapons under his feet. The same cannot be said to the Punjab, where the army’s professional troop was deployed to monitor the exodus triggered by the partition. Once he convinced that the Bengal had passed the most testing time, he made his journey to Delhi, as India’s capital is getting out of control. With the communal hatred reining senses, the Hindu and Sikh migrants from Pakistan and the displaced Muslim population in and around Delhi resided in the refugee camps.

To bring sense to his fellow Indians, for the last time in his life Gandhi yet again put himself in the forefront by employing the most lethal weapon in his non-violent quiver- Fast unto death. The hatred filled Indians responded with slogans of ‘let Gandhi die.’ With his un-shattered dedication for the cause at hand, the Mahatma put himself at just an inch away from death through fasting. The hatred was defeated by the unending love of the advocate of peace.

His conditions to stop his fast were met, one of which paid Pakistan their money due to them as per the partition agreement. The then Indian government delayed it, fearing Pakistan may use to buy arms that will be used against the Indian soldiers. To make Mahatma stop his fasting, the Indian government released the money, saving Pakistan from bankruptcy.

Another condition Gandhi had laid down for ending his fast was that the festival celebrated at the Quwaat-Ul-Islam should go on unimpeded. To his surprise, Gandhi witnessed the fruits of his fast at the festival.

‘Hindus and Sikhs who, a fortnight before, would have welcomed Moslems to Mehrauli with daggers and kirpans, stood at the entrance to the mosque decorating the arriving pilgrims with garlands of marigolds and rose petals. Inside, other Sikhs had set up little stalls at which they offered pilgrims free cups of tea. Mingling with that enormous, fraternal crowd of Moslems, Sikhs, and Hindus, his hands-on Manu and Abha’s shoulders, Gandhi was moved almost to tears’.

For his actions, words, and firm beliefs, Gandhi was labeled as ‘anti-national’ and finally killed by the Right-wing fanatic- Nathuram Godse, for opposing the idea of Hindu India. Gandhi envisioned India, where people from across the religions would live in harmony and spread his message of non-violence and peace. He preached, practiced, and finally died for his vision of India. It would be appropriate to end this tribute to Mahatma with what Hindustan Standard published after his gruesome murder.

‘Gandhiji has been killed by his own people for whose redemption he lived. This second crucifixion in the history of the world has been enacted on a Friday – the same day, Jesus was done to death one thousand nine hundred and fifteen years ago. Father, forgive us.’

Featured Image Credits: Needpix