Encounter and the value of Myth

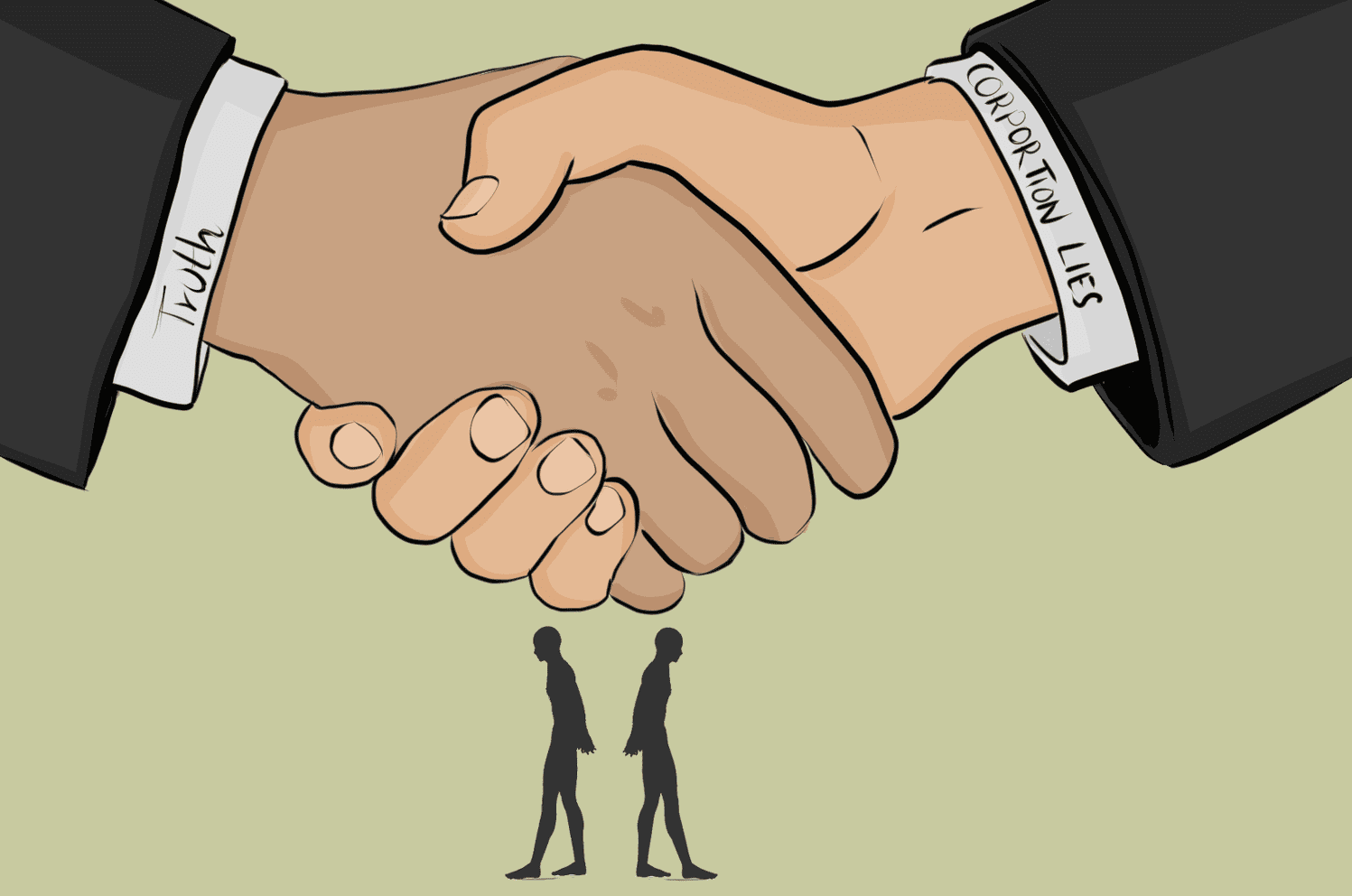

Humanity depends on moral norms and positive values such as truth, honesty, cooperation for its persistence, and yet it thrives on immorality, untruth, corruption, and conflict. However, these two sets of values, though, may seem antagonistic, do not always pose distinct extreme options. Rather, lies need to be told as truth many times. It can’t stand on its own always, and that is reflective of its moral emptiness, though it may have high utility in certain circumstances or even generally in society. A deft act of corruption requires a peculiar kind of honesty between the actors, which ensures that they’ll divide the benefits fairly and be transparent with each other. Similarly, even two warring camps need to cooperate on the adoption of some mutually acceptable norms of the warfare, be it the Mahabharata war or modern conflicts between nuclear states. Therefore it can be reasonably argued that all sorts of immoralities or aberrations require some moral framework or the guise of morality for their public justification.

Inversing hierarchy of values

As the popular theory of origins of society and politics propounds, a range of social and political institutions were contracted out amongst people when the competition and conflict stemming from unequal strengths made peaceful communal living impossible. Consequently, political apparatus, namely Courts, police, and political parties, appeared to ensure cooperation and peace by the means of bloodless resolution of conflicts existing in society. This political system established another set of ethical-legal codes such as procedural justice, law and order, and human rights, which were meant to minimize the excesses that may be arbitrarily targeted against some powerless individuals or sections of society.

The utility of these principles has, in the past years, come under severe debate from above and below, which has seen a declining belief in lazy courtrooms, groups overtaking law to punish ‘offenders,’ and a contest between human rights of the ‘civilians’ and that of armed forces.’ Populist leaders across countries have managed to inverse the hierarchy between means and ends, procedures and outcomes, and significantly between truth and narrative. Thus it is no longer puzzling to realize that while American newspapers and Indian fact-check websites are employing their energies counting fake claims by respective top leadership, the leaders are themselves busy on new scripts. Truth or falsity of the dominant narrative doesn’t affect its validity as long as it’s appealing to the newly awakened sentiments or senses of the people. These scripts thrive on the psychological want of satisfaction to the frustrations that have been produced partly by the failures of procedural democracy in delivering justice, civic education, and worth to the individuals. Myth owes a lot for its desirability in identity-crises ridden society to the failure to incorporate truth and justice in a successful mechanism of public welfare.

Procedures, efficiency, and justice

Thus outrage over Delhi gang-rape case of 2013 and sheer impatience over the delay in the hanging of Ajmal Kasab were manifestations of eroded public faith in the efficiency of police order and judicial system as well as it provided a space where the delegitimized state could bargain for its legitimacy by offering the masses a sense of participation in governance, though that didn’t happen, and even in justice delivery through mob action. On its part, the judiciary tried to accelerate its working by establishing fast-track courts, but neither infrastructure nor judicial appointments could be fast-tracked. At the same time, when the judiciary was failing, the executive was remarkably successful in valorising the army and police, demonising offenders and perceived offenders, and politicising potential threats posed by the ‘surplus’ population. Thus, the state and its people came to an implicit understanding that offenders need to be neutralised to contain the threats that may arise or have arisen regardless of the legal procedures and constitutional moralities that are perceived to have obstructed, for a long time, the road to security and justice. Indeed it was that feeling of participation in eliminating ‘rapists’ that was evident in cheering for and garlanding of the policemen after they had shot four rape accused in Hyderabad dead in December 2019. In turn, it is this active consent that encourages Police and politicians to adopt a short-cut to win support and legitimacy by deploying force directly to the alleged people.

Need to retain the Myth of Law

The Hyderabad encounter last year encouraged several demands from families of rape victims across states to shoot their culprits in a similar fashion, which further added to the power of the police, which had already flexed its muscles on anti-CAA protestors earlier. However, Hyderabad was an opportunity for the police to sharpen the art of playing to the gallery. In fact, the recent encounters can be merited for their ‘untruth value’ if nothing else. The charm of the event lies solely in the apparent falsity of the story, which makes it enigmatic else it could easily have been staged a little better and realistically. Further, these encounters are a perfect blend of an unreal story with real punishment and satisfaction of retributive justice.

Nevertheless, it’s tempting to ponder that in spite being aware that the people, the state itself, and the media, all would be only smiling at the incredible stories of flat and punctured tires leading to more than five encounters in a week, why is there a need to stage the encounters and dress them as accidents, when there already seems to be acceptance of extra-judicial killings as fair punishment. The only plausible explanation for this duality seems to me is that there is still that wide consensus on the need to retain the myth of law and procedure for large and diverse countries like ours, or even smaller societies cannot function in the absence of procedural uniformities and predictability. The norm is, to tell the truth, follow the law, and be honest. And excuses cannot be justified in institutional language though celebrated covertly.

This opportunistic excuse from law, whether by the masses or by state institutions and backed through the consent of each other, is dangerous for both. For the identity of the targets of a mob, punishment, as well as police excesses, may not remain the same and such that both can always agree upon. ‘Nationalised’ vision should rid of its hypermetropia to see around in immediate localities the bare living testimonies of police excesses. The Policemen will also need to understand that the breakdown of the order can hit them equally, and someone like Inspector Subodh Kumar Singh would fall target of street violence. Therefore this secret coalition of comforting conspiracies is threatening for both people and state though the targets; the arguments and the cheer-leaders will change with time.

References:

- Lewandowsky Stephan, ‘Why people vote for politicians they know are liars’ , The Conversation. December 19, 2019

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia