Ashoka University- Of the elite, for the elite, by the elite

Srinath is the Founding Editor of The ArmChair Journal. Currently at the University of Chicago, he is also an alumnus of IIT Madras, Ashoka University, Rishihood University and Purdue University.

Ashoka University is a philanthropic success and I was part of the Young India Fellowship (YIF) cohort of 2018-19. I greatly benefited from its philanthropic model as I received a full-tuition scholarship, and the administration provided me with a laptop when the one I had stopped functioning. To get to the point straight, my concern for this essay is not to present another rosy picture of the university, but to highlight hibernating criticism on some matters. There are already enough valid perspectives on how successful the university is, and I would not add much to that.

Before I begin, I owe an apology to my friends, batchmates, and other stakeholders who might be offended by this essay. Though my experiences are limited to the YIF program, my hunch is that matters I would highlight are worse among the undergraduate students who occupied more space on campus.

There are many great things about Ashoka University. Academically, Ashoka is made of star professors. On a pleasant morning on my way to the mess, I saw Prof. Sudipta Kaviraj crossing the lawns. I thought I was mistaken. At Hyderabad Central University (HCU), a visit from Prof. Kaviraj attracted students who attended his lecture like flocks of sheep and the auditorium itself was too small a place to hold us. At Ashoka, his presence was casual among many stalwarts. I later learned from a friend that Prof. Kaviraj also taught a course at the university. While Prof. Pratap Bhanu Mehta was the Vice-Chancellor, many big names of India’s intellectual landscape had visited the campus during the year: Yogendra Yadav, Rajeev Bhargava, Ramachandra Guha, Subramanium Swamy, and so on. It was not rare to see the former Chief Election Commissioner S. Y. Qureshi standing in the long queue for food in the mess.

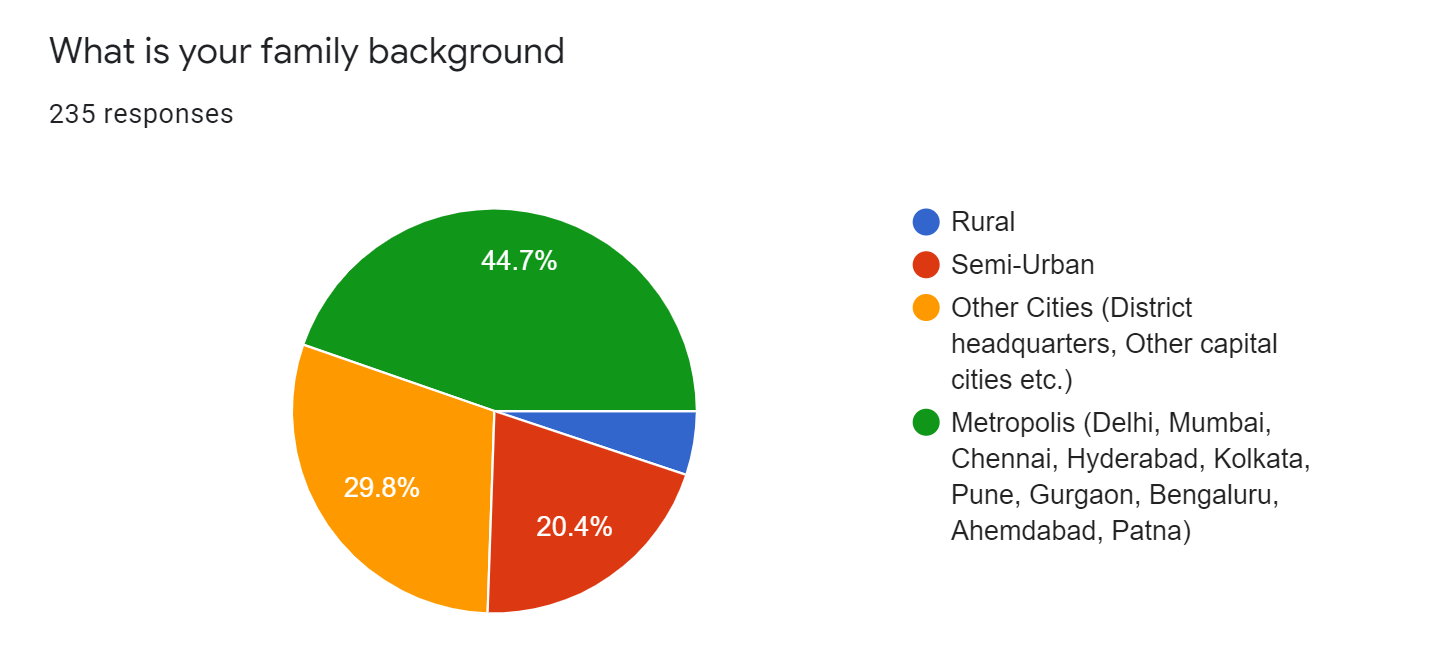

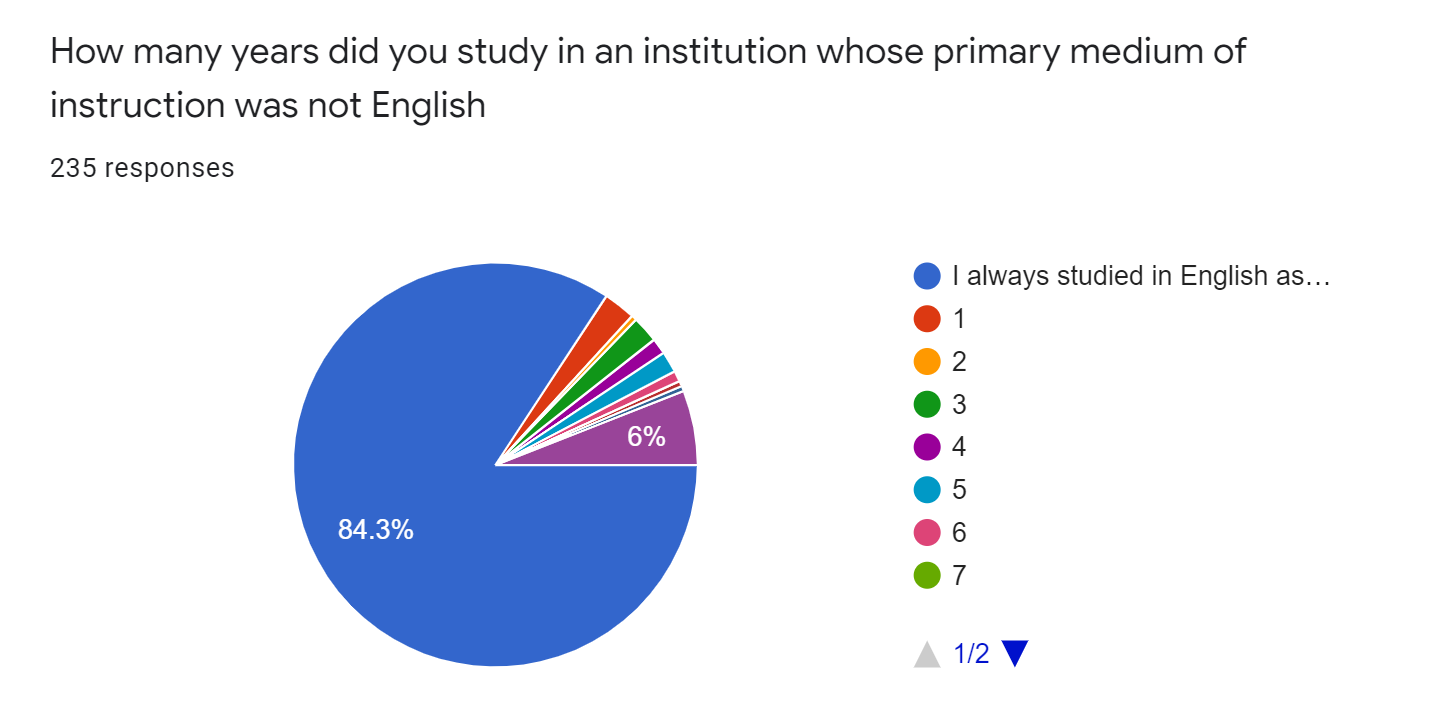

The star faculty, liberal culture, students from elite backgrounds and student-friendly administration were the norm. The university’s target customer was someone who was excellent at English, came from a reasonably rich family, upper-caste, uncompromising, and had aspirations of infinite freedom only the elite could dream of. Hence, the fee was too high even for an above-average Indian family to dream about. Scholarships were given of course, but it is only debatable if they served the best purpose. By targeting such a set of students/families, the university saves some foreign exchange for India and also maintains its liberal culture. It promises the standards of well-established Ivy League institutions at local comforts and prices.

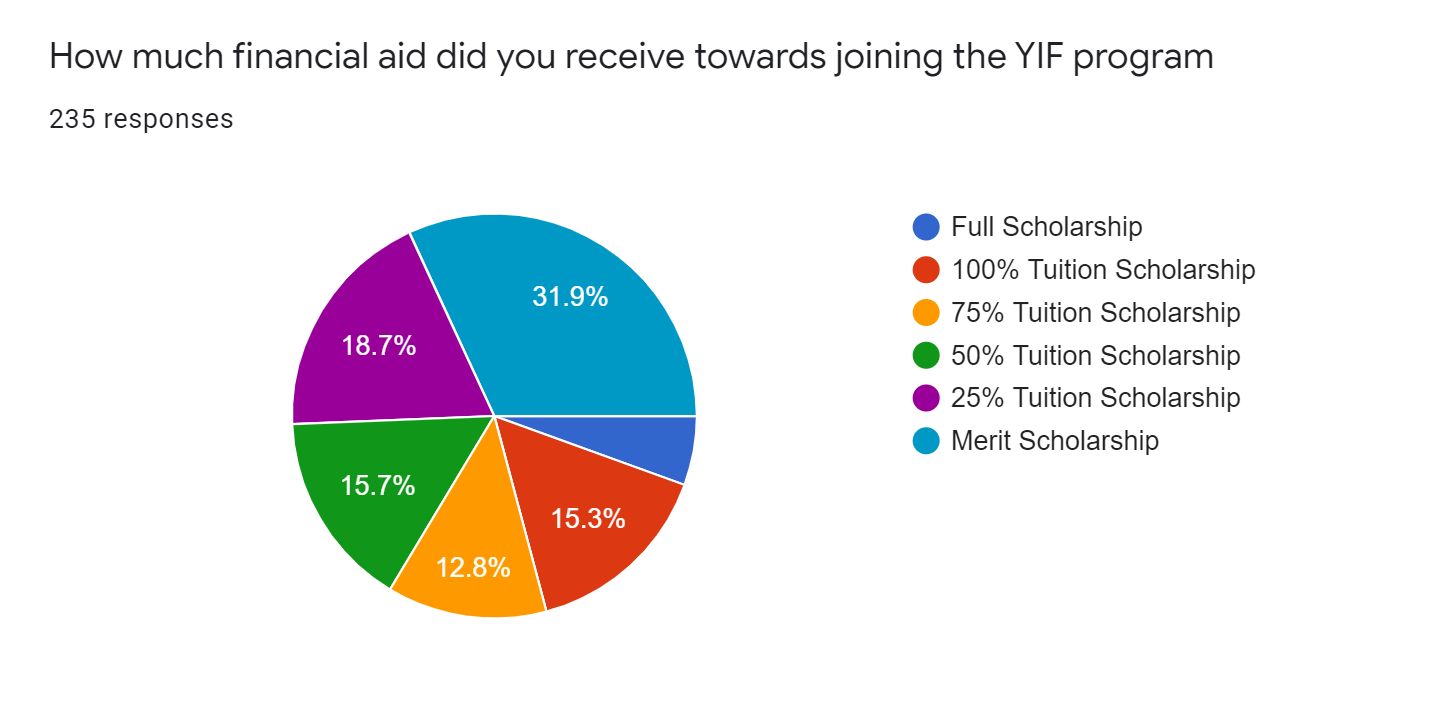

However, the situation appears grim on several vital matters that I would take up towards the end. Our cohort had participated in a survey with indicators on inclusivity and diversity of the batch. The survey was passed on to us from the previous batch. 235 fellows had responded out of 290. While the PG Diploma in Liberal Arts program boasts of diversity- it is limited to the likes of diversity between a commerce graduate and an arts graduate; Fellows with work experience and Fellows without and the ilk. Here are some charts to introduce you to our cohort. I do not claim objectivity in the survey of any manner, but just sense. Take it with a pinch of salt.

Philanthropy and Equality of Opportunity

In one of the conferences I attended at HCU as a student of political science, a professor observed that Capitalism keeps coming back. It is an amoeba that reshaped itself to address all concerns while preserving its basic qualities which could be summarized as individuality, self-interest, profit maximization, competition, meritocracy, right to property, and engagement of labour through an unequal contract–more or less, the features of the markets.

Capitalism suggests forwarding great ideas. Through market competition, best ideas are those that fuel progress and innovation. A layman like me can also understand most of the markets through supply-demand curves. The system appears to respond to criticism against it and keeps resisting or postponing reforms including that of justice. Start-up culture, incubation support, venture capitalist funding, easier access to credit, workers holding ownership in companies through shares are all innovations aimed towards preserving the system and realizing its potential. While capitalism pretends to listen to all criticism and stays vigilant to preserve its basic features, its opposition is almost always found guilty of lack of an alternate proposal which makes the opposition appear as if critiques are aimed at collective poverty, and hindered progress.

If you say poverty, neoliberalism says it generates more wealth and enlarges the pie. If you say climate change, it says technological innovation. For consumerism, it says individual choice. If you say caste, it started saying Dalit capitalism. Sometimes, it marches in the name of pragmatism. For self-interest and greed, it says human nature. If you said economic inequality, it gives you philanthropy. Philanthropy makes us feel as if neoliberalism cares about society as much as it does about the individuals.

Philanthropy has helped millions of people across the globe. An important feature is that it is subjective to the individual donor, while capitalism is a structure nurtured over generations, if not centuries. When philanthropy becomes structural and is determined by rules rather than being voluntary, it becomes another form of taxation. Hence, philanthropy can only exist as a voluntary feature, as a choice made by the individual. Though voluntary, whenever a philanthropist donates their riches, capitalism takes credit for the ‘good’ deed as the generation of such wealth was possible only through capitalism.

The dynamism of capitalism keeps distorting equality of opportunity in various ways: the unequal contract shared between the worker and the owner, for the owner to capture the surplus of all labour; the right to property individuals are entitled to, as part of their dynasty; and the ability of markets to commoditize everything towards making accessibility difficult for many. If not checked, these barriers amount to failure of neoliberalism itself, due to the easily identifiable differences in the opportunity for all it guarantees. Hence, the purpose of philanthropy must be to mitigate these distortions, by targeting such sections which are denied opportunities. Whether the philanthropy of Ashoka addresses these is debatable.

Higher education and private institutions

Since private higher education raises funds from tuition fees, the growth of private universities is a rising concern in equal access to higher education. Only the rich get benefitted from private education that is designed to cater to markets. The same group has controlled the means of production across generations. Hence, the only way lower classes can dream of social mobility is through acquiring skill. When access to higher education is denied, they are left with no means to attain any skill. More private education means more differences in skills obtained across classes. The system becomes self-serving and neoliberalism becomes a private affair of nepotism and dynasticism, aggravating class divides and inequalities.

Ashoka University is seen as a philanthropic success by bringing many industrialists together. It seems to correct the faults of privatized higher education by raising some of its funds through philanthropy, rather than from tuition fees. The argument that private higher education does not provide equal access to everyone is dealt with in this arrangement, to some extent. However, when we look at the eliteness of our cohort, the university sounds like an arrangement the rich made for themselves to not let their children go abroad, instead bring the faculty back to India for quality education. It sounds like a home tuition centre within the country for the elite. Its philanthropy appears to gather the support of the elite, as it solves their problems. An elite innovative solution for elite problems.

Further, the upper-caste nature of the institution also means that whatever scholarships are offered through philanthropy, benefits students from the ‘general’ category disproportionately. Students from the lower castes cannot even imagine to apply as the fee charged despite scholarships is exponentially exorbitant. The campus is sanitized of caste issues as there is little to no representation of students from lower castes. It must be observed that close to 28% of ‘agents of social change’ were not even aware of their caste identity. Meritocratic nature of the institution might also be because the philanthropists might not appreciate the presence of students from lower castes, for their understanding of merit could be blind to privilege.

Many of the liberal professors at Ashoka criticize the BJP for their exclusive nationalism, without acknowledging the exclusive education the university perpetrates. I always wondered how professors of such high esteem agreed to teach at the university. Justice is always perceived to be a hurdle when we are preoccupied with progress.

Philanthropy does not acknowledge oppression

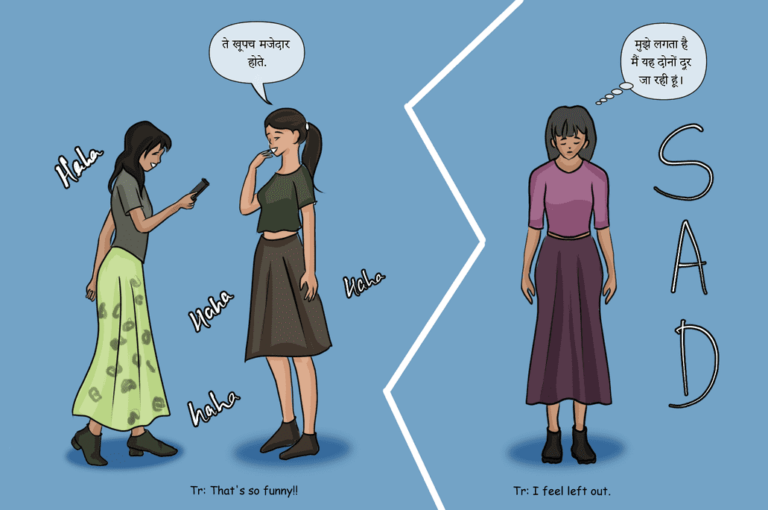

The Ashoka University campus is one filled with love. It was the most liberal of the three universities I attended in terms of sexual freedom. During Autumn, as the plants greeted the seasonal change with colorful flowers, the undergraduate students of Ashoka, often responded with exchanging kisses in little open spaces. Gender and sexual expression were paid relatively higher attention on campus, both in terms of knowledge, and practice. There was no other USP for the campus culture except sexual freedom. On most other fronts: college fests, politics, or even campus lingo, it lacked culture as the campus was young, and culture takes time to grow.

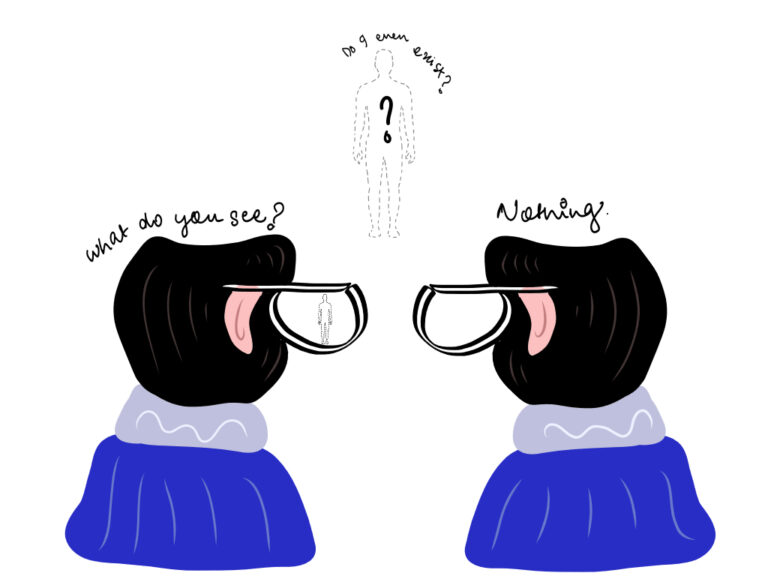

However, experiencing freedom at Ashoka was not easy. The little campus was maintained thoroughly and everything was meticulously planned. Strict routines were followed at the mess and canteens, for gardening, classes, laundry, air-conditioning, and almost every activity one could imagine. I felt most of the time that Fellows were out of imaginative capacities to talk on any matter–not because we reached our limits of imagination every time we tried to, but because we could not imagine anything out of campus affairs. Any conversation would inevitably be anchored to something already existing/happening. Packed schedules functioned more towards stopping imagination rather than enhancing it. Minds felt hijacked and creativity had an invisible ceiling. Surveillance would not be needed, when a meticulously planned routine was enforced. The liberal arts university simulated a corporate work environment rather than nurturing a place of freedom and imagination.

It is important to doubt that the origin of philanthropy is not in capitalism. The campus had a peculiar love for the offices of the underprivileged- the guard bhaiya/didi who kept everyone safe, the janitor who cleaned the toilet commode, the attendant who helped to arrange mics/logistics. The campus did not love the person, or the human, but only the ‘guard bhaiya/didi’, or the ‘janitor’, or the ‘attendant’ as such- the offices of the underprivileged. It even had a little farm and a community who sold vegetables in ‘Ashoka Farmers Market’. No one really loves professions like professors, engineers, academicians, doctors, and so on- they are instead, respected and aspired for, as much as they are loved. I could not feel this peculiar love in other universities not run by philanthropy but by the government, funds raised through taxation. What explains the reason for this love? Existence of such an unsolicited love meant that there was an acknowledgement that something was wrong. However, since both philanthropy and love happened at the level of the subject, both of them do not seem to acknowledge the existence of exploiting structures. Both love and philanthropy could be results of individuals imagining themselves as discrete units, rather than as a part of a structure- as neoliberalism dictates. As individuals, each one does their bit with good intentions.

When the target customers are shifted to other groups like students from lower-income or lower-caste families, we can only doubt whether the support from philanthropic elites would still exist. The idea would be unsettling their privileges, which they misattribute to their merit. Opposition to such a change in target customers would mean the denial of social structures that influence social relations. It also means to justify the structure and their own privilege, which the structures of capitalism and caste make them read as merit.

The university’s denial of equality of access makes it part of the problem. Support of the powerful elite who excelled in the system means it aggravates the functioning of the distorting system. In times to come, Ashoka University could become a world-class research institution. But it would also remain as a university of the elite, for the elite, and by the elite. If Ashoka University is accepted in its current form and looked at as a model to be replicated for many other universities like Krea University, such an acceptance is the final nail in the coffin for social justice and economic equality.

If India is yet to have its ‘Truth and Reconciliation Commission’ for its exclusionary structures, only time will tell what side of history Ashoka University would choose to ally with.

*The author likes to thank Deepish, Abhinaya, Anirudh, George, Siddartha, Irina, and Santhosh for obliging to proofread/improvise the writeup.

*Views expressed are personal opinions of the author. They do not represent the views of the YIF batch, or the platform.

*Author’s learnings from several courses at the YIF are also incorporated in the writeup.

Featured Image Credits: Parnoshree, Tanmay Parasramka

Very good written story. It will be useful to everyone who usess it, including me. Keep up the good work – i will definitely read more posts.

It seems that the university is caste blind in thinking about philanthropy. Out of the 250 something students who have responded, 85% are general.

Your opinion somehow either lacks specific data or contradicts the data you have provided for us.

1) Existence of such an unsolicited love meant that there was an acknowledgement that something was wrong

This is a very troubling observation from you. May i know the basis of this observation ? First time in my life I have heard someone proposing this theory, so I am kind of stumped. What do you think is wrong with the faculty of Ashoka ? You mention that they are very good ar their job. Are they discriminatory in nature ? Or perhaps sexist ?

2) The university’s denial of equality of access makes it part of the problem

Any supporting information regarding this ? Who have been denied or discrimininated against based on caste , gender or religion ? If this is true we need to definitely report this to UGC with proper evidence. Can you share more insight on this ? Your scholarship pie chart shows plenty of fellowships available. Are these discriminatory in nature by any chance ? You mention that part of is merit based scholarship. What are the other parts based upon ?

Any light you throw will be very useful for us.

How much money paid to this not by the con-gress party? Everyone knows how faculty is appointed there