Paracosm – A less reflected take on “Atrangi Re”

Atrangi Re is reviewed as “funnily weird” by several reviewers. But, what about that silent and possibly uncomfortable talk about the mental health of the protagonist?

A. L. Rai and Himanshu Sharma bring in their magic as the director and writer duo after Raanjhanaa, together, working with huge names like Akshay Kumar and National Academy Award winner, Dhanush. After the disastrous performance numbers of “Zero”’ at the box office, Rai tries to tell another love story. Here he silently encompasses mental well-being along with “paracosm,” which is at the core of the tale told.

Rai says, “It comes from just one thing… that is you are willing to fall in love. We are scared of falling in love because we are scared of getting hurt. The minute you get rid of that fear, you will understand people and their emotions better. I have been fortunate enough to meet people who are so willingly available with all their emotions.”*8

On the contrary, Rai gets me a bit irked and makes me contemplate if we are all just given a larger goal than achievable. “Willing to fall in love” is one thing but resorting to a bit of manipulation, even if it’s positively portrayed, to save one from shock to get what we wish for, is something else.

Let me give you a brief summary of what I saw.

The main character Rinku played by the budding Sara Ali Khan is a girl with paracosm. She lives in an imaginary world where Sajjad, played by Akshay Kumar, is the love of her life. She runs away from home, gets beaten up by her grandmother and is trashed avidly but never says who she is running away with.

Dhanush or Vishu on the other hand visits the village for work and is kidnapped and forced into marriage with Rinku. Vishu is supposed to get engaged in two days and fears losing his degree as he’s going to get engaged to Mandy, who is the daughter of his medical school’s dean. He’s advised by his friend MS that he should quietly go ahead with the engagement and nobody will get to know anything. But things go south as Mandy’s family finds out. They misbehave with Rinku and Vishu calls off the wedding. A beautiful track by Arijit Singh composed by A.R. Rahman plays in the background as the plot moves forward.

On reaching the hostel, Vishu confesses his love for Rinku in an almost 5-minute-long Tamil monologue. They hug, but then Rinku hears Sajjad from a distance and runs towards Sajjad, leaving Vishu in tears. It’s not the first time we see Dhanush dejected by the girl he loves while working with the same director.

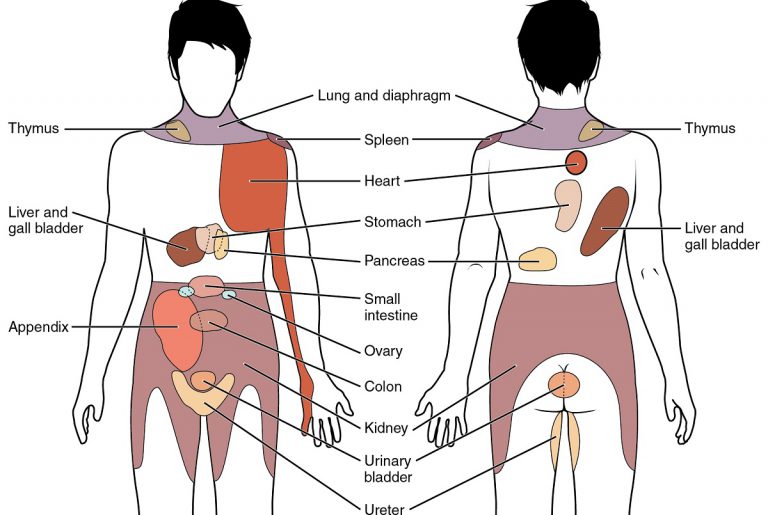

Eventually, Vishu and MS find out that Sajjad is a fictitious character whom she created in an imaginary world where her father’s character is Sajjad and she is in love with him head over heels. They give her medicine but every time she consumes it, Sajjad is badly hurt.

To show Vishu how incredible Sajjad’s skill as a magician is, she takes him to the Taj Mahal, claiming that Sajjad will make the Taj Mahal disappear. That is the first time she realises she has been let down by Sajjad for not being able to perform the trick. After a series of various other events and a “little, little” track sung by Dhanush himself, Rinku realises that Sajjad was her father whom she had seen burnt alive.

She had created an imaginary world to accommodate and come to terms with the death of her parents who were burnt right in front of her eyes.

Incidents like these, or any adverse event in a child’s life can lead to paracosm, seeing her parents burnt to death in this movie was the trigger to that.

A very in-depth and detailed world is created by Rinku right from her adolescence. She has an imaginary lover with whom she’s caught every time but the lover is never there to receive her and help her run away. She creates a world stepping into paracosmic reality by listening to Sajjad, caring about his feelings and believing he’s real and sitting right beside her. She slowly realises the truth and comes out of this.

Additionally, Rinku’s love for Vishu, which she at a point in the film says, “ek ladki ko dono nahi mil sakte?” (Can a girl not have both people in her life?) is where the paracosmic blur slips in.

“Sometimes people take their imagination and their fiction world beyond limits which leads to a condition called paracosm, a range of mental experiences, mediated by the faculty of imagination in the human brain and marked by an expression of certain desires through vivid mental imagery.*7 In this case, Rinku’s entire world was covered with Sajjad’s antiques and the powers he had as a magician as we can see in the movie, the amazing CGI elephant from which Sajjad runs down with balloons in his hands to meet her.

“Researchers see the use of the paracosm not only as a creative mechanism but also as a coping mechanism. Theories assert that paracosm results from childhood unhappiness and that the creation of such an imaginary world may be a defensive and compensatory act of self-care.”*2. The world has its own geography, history and even language and the condition is usually experienced during childhood and continues till months and sometimes, even years.”*1 The most famous example of a paracosm is J. R. R. Tolkien’s “Middle-earth”, the fictional world in which his famous works The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings are based.”*4

“Psychiatrists Delmont Morrison and Shirley Morrison mention paracosm and “par cosmic fantasy” in their book Memories of Loss and Dreams of Perfection, in the context of people who have suffered the death of a loved one or some other tragedy in childhood. For such people, paracosm functions as a way of processing and understanding their early loss. They cite James M. Barrie, Isak Dinesen and Emily Brontë as examples of people who created paracosms after the deaths of family members.”*5 The central theme of the movie is “paracosmic fantasy”*6 and has less to do with falling in love, even though Rai would completely disagree with me.

The character is in anguish and cannot differentiate the reality with her paracosm. Rinku as a character is extremely strong and does not take the torture in store for her post her parents’ death by the family she’s left to live with. The environment she is in makes her create a fantasy world for happiness which works as an antidote to the toxicity of her reality.

We wish to romanticize mental health but it’s not as easy as shown in the film. Real people with real problems internalize it more often than not. For me, Atrangi Re was a brief experience of how mental health doesn’t take a complete back seat but is portrayed in the most Bollywood way possible and by that the conversation around it is not just trivialized, but it does not happen at all. For how long do we have to fear being asked these uncomfortable questions with solutions by professionals?

Mental health conversations started by celebrities like Deepika Padukone or Sonam Kapoor have an all-around impact on society. Their real-life experiences resonated with the millions of audiences who watch and follow them every day on social media or on television. Definitely, we need to talk more about the mental health of the millions residing in this country, requiring more of these conversations.

More power to all those people who are trying to achieve an objective experience also known as “happiness”. Everyone is leading their day-to-day lives with a larger goal of attaining happiness and contentment in the end. Some find it in work, some in music and others in other things; the idea of happiness for 775 crore humans varies and can’t be seen under a single radar. Mental health advocates need to carry the conversation forward and more discussions on the same are needed around the country.

When commercial moviemakers and formula film-makers try to take a subject which includes bits of mental health, they need to keep in mind that there’s an underlying discussion that should take place parallel to “falling in love.”

Surely put your heart ablaze, on fire and let it burn. Don’t let the kindled positivity in you ever take the back seat. But the makers need to address the elephant in the room too, and that is talking more about the mental health aspect of the main character and the nuances with which it comes up.

It needs to be polished with lesser Bollywood “tadka” and more of having maybe discussions on love, happiness and definitely, mental health by the cast and directors along with mental health activists. Maybe it’s high time the Bollywood industry comes out of the “hush-hush” around mental health.

Maybe one lesser Sushant Singh case or thousands of suicide cases daily by students would find some light and support groups can be there or created for people in need of counselling and therapy.

References

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paracosm#cite_ref-5

- https://www.indiatoday.in/education-today/gk-current-affairs/story/paracosm-276382-2015-12-09

- https://medium.com/write-to-inspire/the-power-of-a-paracosm-5676878f0cdc

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fantasy_(psychology)

- Morrison, Delmont C., and Shirley L., Memories of Loss and Dreams of Perfection: Unsuccessful Childhood Grieving and Adult Creativity. Baywood, 2005. ISBN 0-89503-309-7

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atrangi_Re

- Kristin Petrella, “A Crucial Juncture: The Paracosmic Approach to the Private Worlds of Lewis Carroll and the Brontës Archived 2016-09-15 at the Wayback Machine“. In Surface, Syracuse University Honors Program, Spring 2009-05-01

- https://www.firstpost.com/entertainment/atrangi-re-is-fun-but-a-very-layered-film-with-all-its-complexities-says-director-aanand-l-rai-10230351.html

The critique of the article is that the film portrays a person with mental illness without portraying the ‘nuances’ and intricacies of the mental illness that Bollywood is much less prepared to discuss.

Fair enough.

But the suggestion of the article that what we need to combat the mental health crisis of our times is more information about the nuances of the experience of mental illness is, I would like to suggest, mistaken and, dare I even say, symptomatic of our inability to deal with it.

In a short but critical essay titled “Wild Psychoanalysis”, Freud writes about this misconception. “It is a long superseded idea, and one derived from superficial appearances, that the patient suffers from a sort of ignorance, and that if one removes this ignorance by giving him information (about the causal connection of his illness with his life, about his experiences in childhood, and so on) he is bound to recover”. This, Freud says, is mistaken. “If knowledge about the unconscious were as important for the patient as people inexperienced in psychoanalysis imagine, listening to lectures or reading books would be enough to cure him. Such measures, however, have as much influence on the symptoms of nervous illness as a distribution of menu cards in a time of famine has upon hunger. The analogy goes even further than its immediate application; for informing the patient of his unconscious regularly results in an intensification of the conflict in him and an exacerbation of his troubles.” Freud argues information overload about the origin, nature and intricacies of mental illness might not just be useless for dealing with said mental illness but can instead worsen it.

What we need to be concerned about, as a society, is not the specific experiential nature of the mental illness. Instead, we need to ask what is it about our contemporary times – where societal taboos are weaker than they have ever been, where we have greater than ever freedom to ‘follow our heart’ and ‘express ourselves’ – that still necessitates such repression that has pushed us collectively into a mental health crisis. In that regard, I would argue, talking about the “fear of falling in love” in our ‘free society’ does more to address the mental health crisis of our day than delivering a barrage of information on nuances of the experiences of Paracosm would do.

In hegemonic capitalist discourse, there is too much importance attributed to knowledge, information and expertise and too little importance to what psychoanalysis considers to be of utmost importance – “working through”. In our hyper-literal times, we are unable to see the act of popping pills as anything but as literally popping pills. Instead, we should see Vishu giving her pills as the film metaphorically portraying Vishu helping her deal with repression. And see the ‘effect of pills’ as what happens when one deals with repression. Rinku here is not, as the logic of identity politics suggests, a representative of someone suffering from Paracosm. But Paracosm is simply a device to portray someone who resorts to repression and fantasies because of one’s fear of “falling” in love, which is 99.9% of us. Vishu is someone who has a secured life at his doorstep, one that promises a life of comfort and luxury – if only he would repress himself. But Vishu refuses to do so. In that sense, it is not Sajjad who is the mythical creature of imagination who evades the logic of contemporary reality, but Vishu.

In so many languages from so many parts of the world, the verb to indicate one entering love life is “to fall” in love. It indicates a traumatic loss of balance, a loss of control of our carefully constructed reality. “We are never so defenseless against suffering as when we love”, wrote Freud. This is the logic of love that has penetrated our languages. In the age of capitalism that promises endless surplus without any loss for anyone, we are repeatedly promised risk-free enjoyment – stimulating enjoyment without risks or vulnerabilities. Profits without risks. Sugar without calories. Coffee without Caffeine. Ultimately, love without “fall”. Love – as simply the fulfilment of our desires, not as a traumatic loss of control of reality. Because shaped by the discourse of today, we would never voluntarily enter into such a contract. But Atrangi Re recognises love as a traumatic loss of control of our reality (shaped by the symbolic) but still asks us to courageously take the fall – if only we are not blinded by the vocabulary of contemporary cultural critique – representation, information and awareness.