Trolley Problem and the war for the control of the economic narrative

Radhika Rishi is a student of Political Science at the University of Delhi. She has a deep and abiding interest in international relations, behavioral economics, and policy-analysis.

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Female” buttontext=”Read out this Theel for me”]

In the classic ethics clash between two schools of moral thought- utilitarianism and deontological ethics, an experiment which is known as the “trolley problem” states that a runaway trolley will run over five people unless it is switched to another track resulting in only one death. The experiment tests human morality and is an example of a philosophical view called consequentialism.

The trolley problem presents itself as a numbers game where the obvious solution would seem to be: choose the path that costs the fewest lives. But empirically speaking, people do not always react to the problem in that way. In a variant where saving the lives of the five on the track involves pushing one man into the path of the trolley, people resist, acting not based on what would seem to be the best outcome, but rather on some felt prohibition or revulsion against killing, irrespective of the consequences.

Unlock 1.0

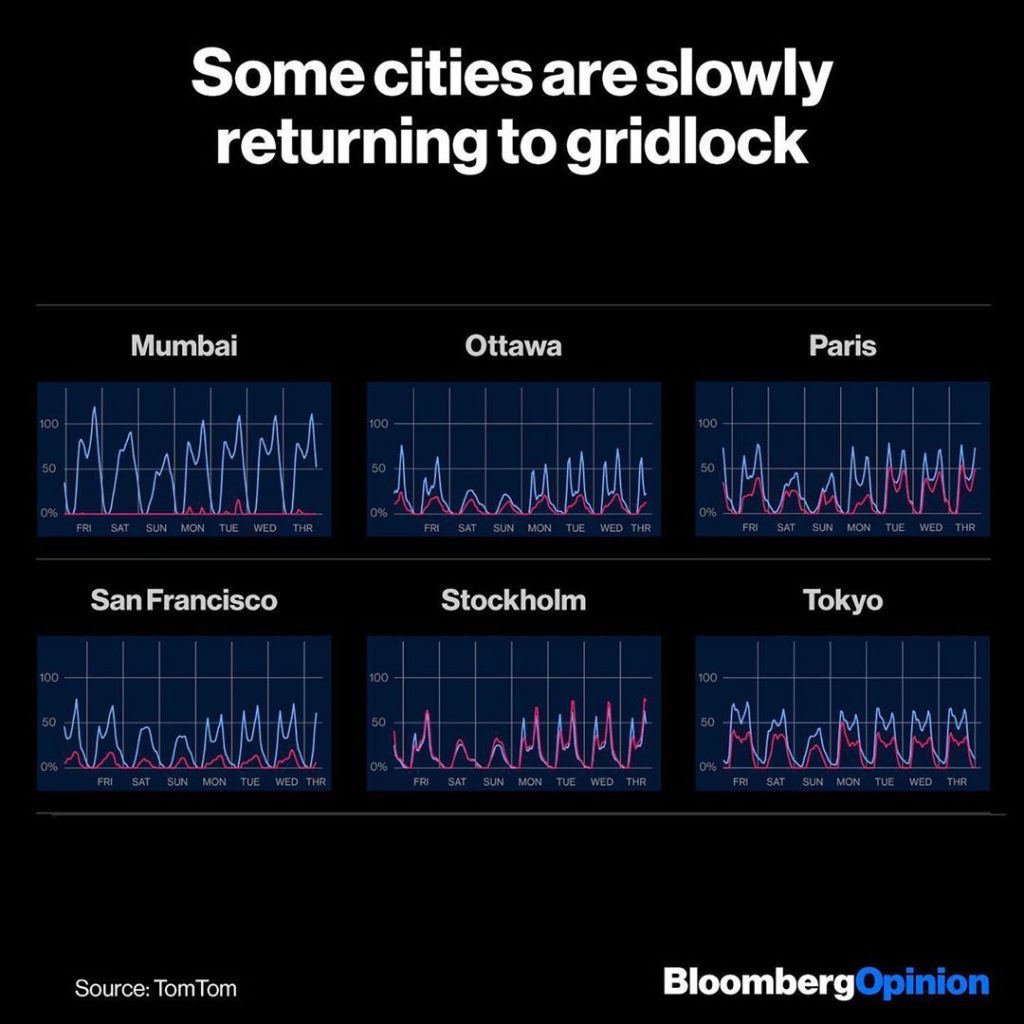

The decisions being made about when and how to relax the lockdown can be discussed as a kind of trolley problem. We have diverted from the track of “normal life” as we make desperate attempts to save lives from the virus. But in the process we have switched over to a track that destroys livelihoods, well-being, economic value, and other goods we care about. The question that is posed is that: when do the costs, the sacrifices made, outweigh the lives that will be lost through the lifting of restrictions? Although many reacted in horror to the idea of sacrificing lives for “the economy,” others pointed out that the costs of lockdown could also be measured in human lives. Some back of the envelope calculations estimates that 10 to 50 million lives will be lost in the long run because of the economic fallout of the lockdowns. Is the cure worse than the disease?

A professor of mine once said that the problem with utilitarianism is that it has “too few concepts.” Her point was that moral decision-making often can’t be assimilated to a single variable but involves qualitatively different and sometimes conflicting demands like duty versus self-realization, justice versus mercy, and sometimes the conversion of a moral dilemma into a utilitarian problem which produces grotesque outcomes. It may be that the question of the proper response to the COVID-19 is related to the demands it generates:

- on the one hand, trying to minimize the threat to human life from the disease;

- on the other, trying to mitigate the damage and suffering from isolation, restriction of movement, unemployment, uncertainty, and poverty.

Without a doubt, they are both absolute moral imperatives.

The new narrative

I remember when the pandemic first came to widespread awareness in the world. I had an intuition that despite the anxiety and inconvenience and, for many, real and immediate hardship, there was one thing that people liked, consciously or not, about the situation: the sense of facing a common enemy. Our lives suddenly became narrativized—the story encompassing every single person on the globe facing a “clear and present danger.” However, even in the early weeks of the pandemic, when there was a sense of relative unity, there were skeptical and irate voices, questioning the seriousness of the threat and objecting to the severity of the response too. Those voices became louder and more strident as the weeks wore on until, it seemed to me, the narrative broke completely into two parts as it had been before the pandemic:

- On one hand, it remained a matter of fighting the virus;

- On the other, it became a matter of fighting against “oppressive” and “deceptive” government responses to the virus, especially those who are misusing the inherent fear of the virus and lockdown to serve their own political agendas.

As of now, the COVID-19 outbreak looks like a giant Rorschach test, those colored ink blots that reveal your personality, except this time it reveals the nature of governments and, more widely, societies. It is fascinating to observe how governments around the world are reacting to the threat. Even if the epidemic soon disappears, eventually, its fallout could be spectacular – for better or worse.

Take China, for example; a country whose government has been keen to promote their autocratic and secretive regime worldwide. The initial cover-up was unsustainable and forced the government into a U-turn that all citizens could see and that was a rare event. The famous hospital which was built in ten days looked like a massive achievement until it backfired when the health system became visibly overwhelmed, in effect abandoning scores of sick people. Though most citizens are under no illusion about the nature of the regime they are under, this is a traumatic experience. Similar observations were applied to other similar regimes. Iran’s unbelievable numbers of reported cases and deaths eventually blew up. Russia followed the same path, as it did with AIDS a while ago. As we have learnt from the Chernobyl example, people are deeply hurt when they discover that their own government chose to protect the regime over their own lives. There is always a price to pay, sooner or later.

Conclusion

So, the war for the control of the economic narrative continues. But in the absence of any shared understanding of our situation and it’s imperative of who or what the enemy is and of what the global destiny is, we can act collectively neither in accordance with some shared narrative nor even some dry but objective utilitarian calculus. We cannot in fact act collectively at all. Instead, things will be determined by a power play—by the competing interests and conflicting narratives of different groups. Some countries reopened right off the bat (pun not intended), some are reopening now while others will extend their “stay at home” orders to try to get things further under control. Some people will blithely congregate, while others will still fear to leave their homes. There will be only piecemeal and drastically inadequate provisions made for the vast number of people whose lives and livelihoods have been jeopardized by the economic crisis.

If this is the case, as it seems to be, then the narrative that we find ourselves inhabiting is indeed a tragic one—not one in which we find ourselves faced with conflicting duties, but one in which we cannot even see what kind of story we are living in at all.