The tenth Winter and the rule of law

Dilip Simeon is a trustee of the AMAN Public Charitable Trust. He formerly taught history at Ramjas College, University of Delhi, and has been active in democratic and anti-communal mobilization for many years.

[responsivevoice_button voice=”US English Male” buttontext=”Read out this Theel for me”]

This article was written in May 1997.

Those familiar with the streets of Delhi will have noticed the contempt with which the police vehicles, large and small, treat traffic rules, to say nothing of the ubiquitous white Ambassadors bearing the middle bureaucracy. This is not only true of officialdom – buses stop in the middle of the road, stop signals are regularly violated, and lanes totally ignored. There is no awareness that traffic rules are for everyone’s safety. When the very authority which is paid to uphold these laws does the opposite, when the lack of civic sense appears to be all – pervasive, one begins to wonder if there is some deeper malaise at work.

Some forms of social derangement underpin all the others. The gap between the claim to being law-governed and the actual observance of rules is one of them. Traffic rules are the least of them. Electoral laws and the Penal Code regulations governing incitement have, until the last general elections, been flouted without compunction. It remains to be seen whether the Election Commission can prevent the misuse of religion and election symbols in future.

When certain top police officers took to preaching inter-religious warfare after they retired, one wondered how they could have functioned impartially while in service. College principals engage in the practice of discretionary admissions, bypassing established procedures, and inculcating amongst the youth the gentle art of queue-jumping. Opinion makers applaud the handcuffing of students who cheat in examinations, but not much is heard of the need to make accountable those teachers who neglect their classes. Elite groups of businessmen and officials mysteriously obtain prime urban land at throwaway prices. The list is endless.

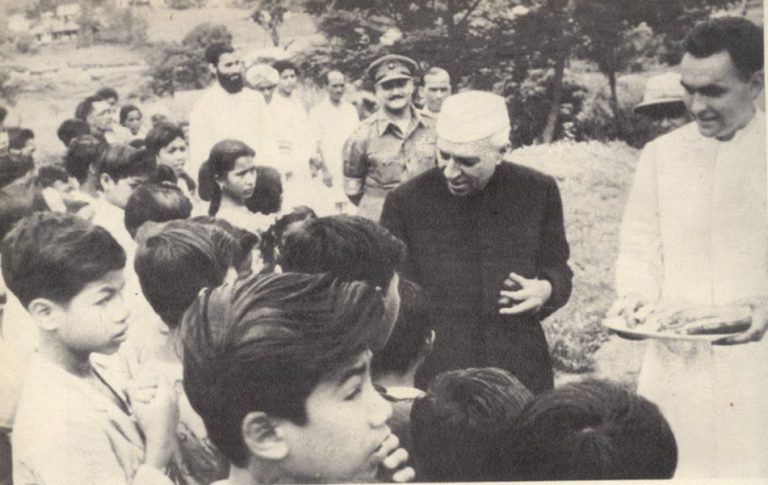

Why grumble at all this? The flouting of rules is accepted with various degree of resignation. Like black money, it is assumed to have its functions. What the ruling castes/classes do not realize is that this attitude has an indelible impact upon popular perceptions of right and wrong. I remember as a child seeing Pandit Nehru and senior leaders moving about in the city and at public exhibitions with ease. Today’s leaders and senior officials live in glorified prisons. Do they realize that this predicament is of their own making?

Across the enormous linguistic distances in our society, certain messages get through clearly enough – some people live above the rules, while the rest of us have to negotiate them somehow. And for the mass media, there are some crusades which may be launched, while grievous issues may conveniently be forgotten.

Thus, Naxalite violence is awful, but if a few thousand people are murdered in a couple of days in the name of God Almighty, this is unfortunate, but inevitable. The greater the enormity, the larger the number of publicists who may be found rationalizing it, using it to make money, or putting their consciences to sleep. I was aghast at the number of gruesome and provocative photographs published by the Gujarati press in Surat, where I happened to be resident in December 1992. In Bombay, Doordarshan telecast a Marathi programme on Shivaji’s weapons on one of the worst mornings during the violence a year ago.

Read More from Dilip Simeon

I sometimes wish that the intellectuals, who rationalize brutality could be made witnesses to these ‘nation building’ activities when they take place; as for instance, when little girls were heinously done in on a train at Udhna, near Surat, on December 9, 1992 (the details are too painful to recount). But I doubt whether this will make any difference. Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, Hitler’s notorious terror arm, which presided over the annihilation of European Jews, once asked for about a hundred victims to be machine-gunned in front of him. The carnage caused him to faint and suffer a nervous fit. But, there was no change in his character or activities.

This is the tenth winter since the slaughter of innocents in India’s capital, an event which, in my view, carried as much import for ‘midnight’s children’ as Partition did for our seniors. (May I repeat here, in passing the demand that the ban on The Satanic Verses be lifted?). For years afterwards, there was a conspiracy of silence about it, matched by the shameless determination of the national government to thwart the judicial process. There is no sign that Parliament will even pass a resolution of condolence. None of the national parties has carried out a sustained agitation for justice. And does it sit easy upon the conscience of the politicians making the latest gestures in that direction that they were themselves the prime movers of violence and mayhem directed against Muslim citizens? These matters are not party issues any more. They concern the legitimacy, not of this or that government, but of the Indian Union. Those who swear by national unity must seriously consider the effect upon state institutions of the undermining of constitutional rules and processes.

Let me underscore the difference between civil and criminal law. The first concerns disputes within relationships of a social or commercial nature. The second relates to the physical safety of the citizens and their property. If there is no such uniform criminal law in India – and such is indeed the case factually, though not technically – there can be no common civil law either, and the moral fabric of society will be torn apart. Yet there is no life without optimism, and Indian society has always carried its own antidotes. I shall make reference again to Gujarat. The purohit of a small temple in Baroda, wrote a moving account of his anguished reactions to the events of December 6, 1992. His views were humane, compassionate and steeped in his own religiosity. He remains a common man, worthy of the respect of many of our VIPs. A news report dated January 12, 1994 tells us that tens of thousands of citizens in Sidhour, Mehsana, took a public pledge of peace, with killers openly repenting their crimes and the families of the victims declaring their forgiveness. The ends of justice and social order requires nothing more.

In the tenth winter since 1984 and the first since the demolition of the desolate Babri Masjid, the citizens of Sidhpur have reminded us of the delicate, tenuous, and profoundly ethical nature of the ties that bind us. Rules must apply to everyone, or there is no point having them at all. And the first rule has to be a respect for human life and dignity.

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia