The anti-national district of India – Least spoken and almost forgotten

In the landscape of contemporary India, a troubling trend has emerged—sedition cases are on the rise. The figures speak for themselves, as revealed by a report from The Indian Express dated May 31, 2022: a staggering 399 sedition cases have been filed since 2014, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). But when we zoom in on one particular state, Jharkhand, the narrative takes a perplexing turn.

A riveting exposé by Supriya Sharma on Scroll, published on November 19, 2019, unravels a hidden truth. Unveiling a trove of 19 police reports from Khunti district, spanning the period between June 2017 and July 2018, the charges laid against over 11,200 individuals paint a disturbing picture of societal unrest. And amidst the labyrinth of accusations, one crime stands out—sedition under Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code. Astonishingly, more than 10,000 people find themselves entangled in this web of sedition, yet this crucial information seems to have been conveniently ignored by the NCRB.

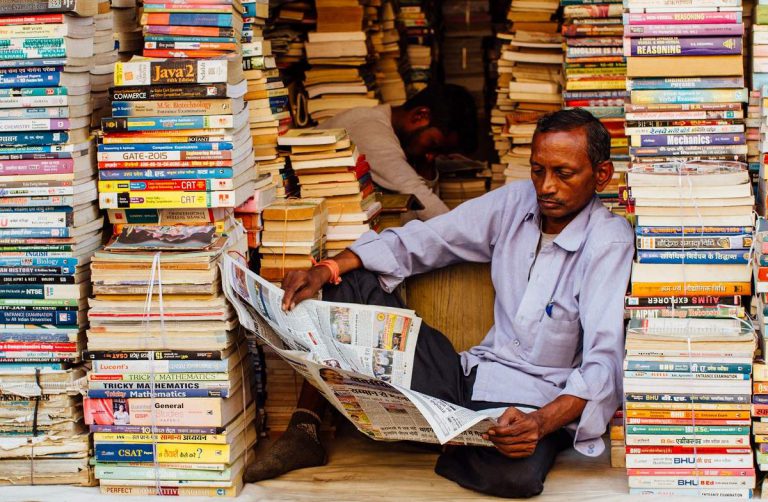

Curiosity compels us to dig deeper, to uncover what truly transpired. It was on that fateful day, March 24, 2023, when I found myself in the heart of Jharkhand, a witness to Sarhul—a vibrant Adivasi celebration that marks the advent of a new agricultural year. It was during this visit that I had the fortune of meeting Aloka Kujur—a poet, a beacon of social activism for women and tribal rights. Nestled in the dimly lit confines of her modest 10×10 room, she prepared a feast, her culinary prowess matched only by her spirit. With a twinkle in her eyes, she jested, “Indulge in the fare of an anti-national and let me know your verdict.” And so, the conversation took a turn towards the crux of her plight—she had become a victim of sedition charges, brought forth under the weight of Section 124A.

But what, you might ask, led to this grim state of affairs? As we perused the pages of her published poetry, the untold tale of the Pathalgadi Movement unfolded before us—a movement that plunged over 10,000 lives of Adivasis into a maelstrom of uncertainty, including that of Aloka Kujur. Her tireless work as a social activist focused on addressing the injustices faced by women in Adivasi traditions. For, in a community where women are unjustly denied a share of the land, the forced displacement stemming from development projects leaves widowed women without a place to call their own. Her collaboration with the late Fr. Stan Swamy, a fierce advocate for the oppressed voices of the Adivasi communities in Jharkhand, aimed to empower these communities through the pursuit of their constitutionally guaranteed rights.

The tale commenced in 2017, merely 34 kilometres away from the state’s capital, Ranchi, in the nascent district of Khunti. It is crucial to acknowledge that this region falls under the protective umbrella of the fifth schedule of the Indian Constitution. The Panchayats Extension to the Scheduled Areas (PESA) Act of 1996 grants autonomous powers to gram sabhas, enabling self-governance for the majority of tribal members. Additionally, two seminal acts—the Chotanagpur Tenancy Act (CNT) enacted by the British in 1908 as a response to the Birsa Movement, and the Santhal Parganas Tenancy Act (SPTA) passed in 1949—stand as guardians of land rights in the region. Their primary objective is to regulate and, to a large extent, prohibit the transfer of tribal lands to non-tribals, safeguarding community ownership. These two acts form the bedrock of understanding the simmering conflict between the state and the Adivasi communities.

As we grapple with these revelations, the contradictions and injustices become starkly apparent. The burgeoning sedition cases, the unsettling disparity between official records and ground realities in Jharkhand, and the stories of resilient individuals like Aloka Kujur beckon us to confront the unsettling truth. It is within this juncture of revelation that we must summon our collective voice, igniting a chorus of advocacy and compassion to address the systemic inequities that threaten to undermine the very fabric of our nation.

The conflict’s origins trace back to a pivotal moment in Jharkhand’s history. On that fateful day, December 28, 2014, Raghubar Das was sworn in as the state’s 6th Chief Minister. Notably, he became the first non-tribal leader of Jharkhand, hailing from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). Under his stewardship, the Jharkhand assembly passed amendments to the aforementioned acts in late 2016, paving the way for the acquisition of tribal lands in the name of “development projects.” This ignited a firestorm of unrest within the adivasi communities, with protests springing forth like a swelling tide.

In a twist of fate, the then-governor of the state, Draupadi Murmu, returned the bills, seeking clarifications on the reforms they purported to bring about. Eventually, the bills were withdrawn, yet this setback only served as a catalyst for the introduction of another bill—the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement Act 2013 (Jharkhand Amendment) Bill. Once again, the assembly passed the bill, awaiting the governor’s final approval. These amendments sought to bypass the requirement for social impact assessments in land acquisition for ten specific purposes. The unfolding events triggered a fresh wave of protests, marked by reported instances of violence rippling across various regions of the state. In a bold act of defiance, tribals in districts like Khunti, Gumla, Simdega, Saraikela, and West Singhbhum, among others, began erecting stones inscribed with the provisions of the PESA and the 5th schedule of the Indian Constitution—a powerful statement of their unwavering resistance. This movement would come to be known as the Pathalgadi Movement.

Aloka Ji, ever the captivating storyteller, regales me with an intriguing anecdote. She reveals that the FIRs targeting social workers in the region—those tirelessly advocating for farmer rights, land rights, educational rights for youth, employment rights, and vehemently opposing forced displacement of adivasi communities—contained a unique entry. FIR No: 99/18 stood out, accusing entire villages and even motorcycles of sedition—a historical first, she chuckles. Astonishingly, it took them two long years to bring this information to light, as the BJP government in Jharkhand spared no effort in launching propaganda campaigns to defame the Pathalgadi Movement. Baseless allegations surfaced, attempting to link the movement to Maoists, Christian missionaries, and opium traders in the region. However, the truth defied these narratives, for the movement was driven by educated, urban, middle-class leaders, many of whom held government positions.

Fast-forward to 2019, and the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha (JMM), a prominent political party in the state, pledges in its manifesto to dismiss all cases related to the Pathalgadi Movement once in power. Yet, according to a report in The Indian Express in 2020, the government has yet to make a move to withdraw these cases through the courts. As we eagerly await the fate of over 10,000 accused adivasis fighting valiantly to uphold their constitutional rights, an unsettling question looms in the air. Amidst the grandiose promise of “Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav” (the celebration of freedom), are we truly progressing toward absolute liberation when faced with such political crackdowns?

The Adivasis of India have endured the systematic oppression of English laws, from the Criminal Tribe Act of 1871 to the Habitual Offenders Act of 1952. Social ostracization continues to plague their existence, as they struggle to live with the dignity that is their inherent right. These communities remain marginalised, their voices unheard in the hallowed chambers of Parliament. At 75 years of age, India still falters in ensuring the constitutional protection of its citizens, while ideological subversion becomes the favoured tool of modern governments, diverting attention from their duties and responsibilities.

How long?

Within the profound tapestry of “Adivasis Will Not Dance,” the literary opus penned by Hansda Sowvendra Shekhar, a luminary whose ink flows from the depths of his Santhal heritage, lies an indelible tale that reverberates with the echoes of social injustice and dispossession. “November is the Month of Migrations” emerges as a resplendent gem, illuminating the travails endured by Adivasi communities as their lands, their birthright, are callously wrested away. Shekhar’s prose deftly paints vivid portraits of these displaced Adivasis, navigating the treacherous labyrinth of their shattered existence amidst the alien concrete jungle. The narrative unveils the insidious machinations of an unjust system, perpetuating the shackles of poverty, exploitation, and violence upon these marginalised souls. Through the power of his words, Shekhar exposes the cruel power dynamics that underpin development projects, casting shadows upon the plight of indigenous communities. As a privileged insider, the author bears witness, lifting the veil of obscurity and elevating these narratives to the forefront of the collective consciousness. Yet, the less fortunate find themselves ensnared, grappling against political forces that seek to exploit their ancestral lands, rich with precious minerals. In this distressing quest, the Adivasis are reduced to mere pawns, caught in the crossfire of opposition politics, their fears manipulated for strategic gain.

As we awaken to the urgent imperative of safeguarding India’s reputation on the global stage, the poignant questions raised by this profound tale reverberate with solemnity. We ponder, how can the act of etching the constitution upon stone be deemed unconstitutional? How does constitutional awareness, an emblem of enlightened citizenship, morph into the twisted spectre of Anti-National sentiment? Is it conceivable that the very government led by the Bharatiya Janata Party perceives our sacred constitution as an entity that defies its own legitimacy, branding it as Anti-National in its essence? And does the persecution of our own citizens under the oppressive weight of sedition charges, a flagrant disregard for their fundamental rights, aid in the cultivation of an impeccable international image for our beloved nation? Finally, we contemplate the selection of Smt. Draupadi Murmu as the president, an act that might be misconstrued as a mere political ploy, a token gesture to assuage the historical ostracization endured by Adivasi communities within our vast and diverse country.

As we grapple with these revelations, the contradictions and injustices become starkly apparent. The burgeoning sedition cases, the unsettling disparity between official records and ground realities in Jharkhand, and the stories of resilient individuals like Aloka Kujur beckon us to confront the unsettling truth. It is within this juncture of revelation that we must summon our collective voice, igniting a chorus of advocacy and compassion to address the systemic inequities that threaten to undermine the very fabric of our nation. In the contemplation of these weighty questions, we embark upon a journey of introspection, seeking to reconcile the ideals we hold dear with the harsh realities that persist. For it is through this introspection, this collective awakening, that we can forge a brighter, more inclusive future—one that upholds the dignity, rights, and aspirations of all its citizens, irrespective of their cultural heritage or societal standing. I conclude with a quote from Fr. Stan Swamy, who worked in this area and with the tribals for their rights and was persecuted by the government under the same draconian UAPA.

They say, ‘Truth will finally prevail’…but how long is it going to take… and how much damage is being done in the process… Questions to ponder

Stan Swamy