Gandhi’s Hinduism: Ethics, Tolerance and Inclusivity for the ‘New India’

With a number of state elections round the corner early next year, it is not unreasonable to presume that like in most election campaigns, the concept of ‘religion’ shall play a pivotal role in determining the outcome of the polls. At a time when conceptualisations of religion can be adulterated by ego-centric political agendas and staunch exclusionary beliefs, it is important to be able to separate the grain from the chaff.

India has a population of approximately two hundred million Muslims that accounts for about 15 percent of the population, while the Hindus make up about 80 percent. However, the modern-day narrative peddled by far-right Hindu nationalists is antithetical to the secular fabric of the Constitution of India. They pursue a medium of rhetoric, in consonance with certain policies, which aim to transform India into a country where civil strife and sectarianism are key to exercising power.[1] This form of religious nationalism has been widely accepted by the general populace suggesting that the average citizen is left perplexed about their own sense of identity. Indians have become a victim of tainted political pontification whose sole prerogative is to elicit power by manipulation of religious sentiments, in order to create communal discord amongst the masses.[2]

In an effort to reclaim our original idea of a secular polity, it is paramount that we distinguish the old shibboleths from the original principles of religious systems. It is in this context that Gandhi and his ideas on Hinduism, as an inclusive and tolerant system of religious beliefs, becomes an important area of academic discourse. While it is impossible to pin-point a linear definition of Gandhi’s thoughts and beliefs from his countless speeches, as well as the numerous letters penned to well-wishers and critics, this essay shall attempt to critically examine Gandhi’s conception of Hinduism by bringing out its complexities and nuances.

In addition, I shall engage with some of the commonly known themes of Hinduism (contemporary and historical) that have been mired in political agendas vis-à-vis an understanding of how the Mahatma came to his conclusions in these themes.

Gandhian precepts of ethics and religion

Gandhi’s early adult life spent in South Africa is said to have had a profound influence on his outlook on religion and more specifically, his ideas of what it meant to be a Hindu. Having defined Hindus as a section of the Aryan race that settled in trans-Indus plains of India, he maintained the firm belief that Hinduism was not a combatant religion that came into existence due to rivalry with other belief systems. In fact, Gandhi believed that Hinduism had its own ‘independent existence’ which could be historically traced back to the ancient period. [3]

Gandhi had an uncanny knack of artfully integrating his religious ideas into politics, thus being unable to create a strict dichotomy between the two categories. More specifically, the learning lesson for the modern-day politician, from Gandhi’s teachings, would be to incorporate a sense of religious ethic into the political sphere instead of imbibing a culture of political militancy into religious factions.[4] This was primarily because Gandhi’s philosophy was one which accepted the notion of truth wherever it was to be found. His ideas were not narrowly constrained biases fuelled by political vendetta, but rather based on his own understanding of Hinduism which aimed to be more accommodative and inclusive in nature.

Although a self-proclaimed orthodox Hindu, Gandhi’s maintained a strong belief in the equality amongst all faiths with the view that they are all legitimate and follow fundamentally distinct approaches to the very same spiritual conclusion. This offered a framework for his engagement with Hinduism, and also for his active interaction with other religious systems. And while Gandhi tried to create the image of himself as an orthodox Hindu, with the aid of his own perceptions and understanding of Hinduism, the conservative section of Hindus did not believe that he adequately met their standard of a person could be considered a Hindu. Simultaneously, there were several nationalist non-Hindus who found his views to be synonymous with that of conventional conservative Hinduism and not sufficiently representative of the entire religious spectrum.[5]

Gandhian understanding of the ‘true spirit of Hinduism’

As previously mentioned, it was Gandhi’s time in Africa which shaped many of his contentions on ethics and religion. He believed that the two had a symbiotic relationship and that the concepts could not be divorced from one another. This essentially led to the assertion that Hinduism was an ethical religion.

Gandhi believed that the tenets of Hinduism could not be restricted to Hindus alone, and that every Indian citizen must be familiar with the vital components of Hinduism in its customary form.[6] While this might sound like the perfect statement to serve the purpose of riling up a voter-base for the contemporary far-right politician, Gandhi’s intention was quite the opposite. While making this particular statement, he was not reconsidering his firm belief in the equal status of all religions.

In fact, Gandhi was a follower of the principle of sarvadharma samabhava which endorsed the idea of ‘equality amongst religions’. Thus, his ideology did not merely postulate an abstract faith in the legitimacy of every religious faith, but rather encouraged belief in a set of fundamental principles which governed the ‘adequacy’ of each religion that a person was born into. [7]

Gandhi asserted that the practitioner of a particular religion had a moral duty at large to understand other religious faiths.[8] While Gandhi firmly believed in the independent existence of Hinduism as an inclusive and tolerant religion, he was also quick to admonish dissidents who steered away from what he believed to be the ‘true spirit of Hinduism’.[9]

In one such instance, he severely reprimanded Swami Shankarananda’s sarcastic comments about Islam which claimed that the religion posed an ‘inherent danger to the Hinduism’ which could be averted only with the aid of the British. Gandhi opined that if he himself was incapable of safeguarding his religion, it would be futile to place his faith in a person of another religious denomination to do the same.

Gandhi believed in reimagining Hinduism internally, so that he could incorporate elements from external sources in an even more successful and seamless manner. Although he had implicit disagreements, Gandhi never strictly adhered to a conservative or a liberal conceptualization of Hinduism. Unlike the current political status-quo, his ideas of Hinduism were not motivated incessantly by the desire to sustain conservative practices or to follow progressive developments. He does not adhere to the conventional norm of divorcing conservatism from liberalism and vice versa. Gandhi was equally skeptical of these stratified dichotomies during his attempt to resolve the differences between substantive faith and rational progressivism. [10]

The need for Cooperation or independent co-existence?

Wilful ignorance or a new-age interpretation of faith was somewhat unconscionable for the Mahatma. As discussed so far, Gandhi would continue to berate faith until he was able to establish meaningful interpretation that was equitable in terms of fundamental moral values and not detrimental to his fellow human beings. This notion stemmed from Gandhi’s unrelenting belief that one could pursue numerous different paths that would ultimately lead to the same truth. For Gandhi, what truly mattered was the ‘end’ and not ‘means’ adopted to pursue it. But this is not to contend that Gandhi’s belief in the equality of all religious denominations coaxed him to loosen the shackles of religious boundaries.

When an eminent Muslim scholar and close associate of Gandhi wrote to him by mentioning that other religious factions could extend support to the Hindu community to facilitate the temple-entry movement, Gandhi took a firm stance by indicating that external interference in the internal affairs of the community was impermissible beyond a certain limit. This deep-seated belief of ‘drawing a sharp line at one’s natural religious boundary’ was entrenched in his concerns about the larger consequences of incorporating non-Hindu religious denominations into an internal affair.[11]

Understanding the need for religious boundaries

Gandhi believed that such incidental encroachment in the religious disputes of another sect could create a fertile ground for non-Hindus to convert and bring in new followers into their own religious group. This could also chip away at the fundamental purpose of the entire movement by turning it into one with political underpinnings rather than one based on religion and culture.[12] Gandhi, through his cherished ideals of Hinduism, was able to firmly establish the need for a demarcation between different religious denominations in order to prevent incidental encroachment, whilst ensuring equality of all religious denominations from within one’s own faith.

According to Gandhi, the moral and spiritual quest for religious identity lay within one’s Varna and altering one’s identity to suit the circumstances would have been contradictory to his dharmic order.[13] He set out to reform the Hindu caste system internally by launching a scathing assault on discrimination through untouchability. However, he did not condone the backward classes attempting to improve their social status by conversion to other religious systems. [14]

Thus, the quintessential Gandhian philosophy of Hinduism is one that is premised on placing all religious denominations at an equal footing. Gandhi’s primary objective was to help other human beings find peace and solitude through his conceptualization of Hinduism- whilst leaving out ample scope for fair critique and civil engagement with all kinds of opinions- provided that they fell into Gandhi’s interpretation of the ‘true spirit of Hinduism’.

Gandhi as the champion of the downtrodden

Gandhi believed that conversion would not be able to successfully deal with the obstacles of Hindu caste. Instead of adopting this short-term remedy, he preferred that people of these socially-backward communities look at the larger picture and collectively push for reformation-oriented changes to reform the institution of caste. However, the road to reformation was one of struggle, suffering and patience which people were not ready to adopt as they had been waiting for a long time. [15]

Gandhi, placing reliance on his concepts of Hinduism, was devoted towards the maintenance of tacit social status conferred by imputation, and not preference. He believed that this was more of a question of one’s obligation to the betterment of society, and all human beings, either Brahmin or scavenger, would have to be treated with equal importance. While Rabindranath Tagore famously tried to create a sense of equity by contending that all Hindus were to belong to the Brahmanical sect, Gandhi might well have desired for everyone to be equated with shudras, the working class- a group of purifying reformers. Gandhi’s notion of radical equal treatment was never premised on a competitive Western individualism, but rather on reciprocal beliefs of non-violence and fraternity. [16]

Concluding thoughts and reflections

While Gandhian principles shunned the notion of caste as an institutionalized system of hierarchy, he could see no discrepancy amongst the concepts of fraternal equity and the operational classes that comprised the Varna system.[17] Though Gandhi’s interpretation of internal reformation provoked considerable opposition as well as a great deal of indignation, it was in many ways unable to fulfil many expectations of the representatives of socially-backward classes at that time.

From what I have expounded upon so far, we can say with certainty that Gandhi’s theistic worldview was universal and predominantly extracted from his self-interpreted conceptualizations of Hinduism. Gandhi would always critique religious beliefs until he was sure that it passed his litmus test of reasonability. Gandhi’s compassionate and benevolent Hinduism simply didn’t exist in seclusion. It was through his understanding of Hinduism that he assumed openness of all other denominations. Gandhi insisted on equal treatment of all faiths by religious denominations. This stemmed from his unyielding belief that if Hinduism could be inclusive and tolerant then there was no reason to believe why other religious faiths could not adopt the same principles.

It is imperative that Indian voters do not fall prey to half-baked, politically adulterated notions of religious animosity. For a seamless election and to ensure the perpetuity of secular principles and fair critique, it is incumbent upon both politicians and voters to treat all religions with an outlook of tolerance, which can be derived from within their own religious fold.

References

- Jaffrelot, C. (2015). The Modi-centric BJP 2014 Election Campaign: New Techniques and Old Tactics. Contemporary South Asia. 23

- Gandhi, M.K. (1987) The Essence of Hinduism (Section-I, ‘The Moral Basis of Hinduism’), Compiled and edited by V.B. Kher, N.B.H. Ahmedab.

- Thapar, R. (1996). Ancient Indian social history: Some interpretations. Delhi: Orient BlackSwan

- Heredia, R. (2009). Gandhi’s Hinduism and Savarkar’s Hindutva. Economic and Political Weekly, 44(29), pp. 62-67. Retrieved November 1, 2020, from http://jguelibrary.informaticsglobal.com:2074/stable/40279289

- Prabhu, R.K., & Rao, U.R. (Eds.). (1967). The mind of Mahatma Gandhi. Ahmedabad: Navjivan Mudranalaya

- Gandhi, M. (1994a). Collected works of Mahatma Gandhi. New Delhi: Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India.

- Heredia, R. (2009). Gandhi’s Hinduism and Savarkar’s Hindutva, p.63

- Gandhi, M. (1994a). Collected works of Mahatma Gandhi. pp.97-98

- Mishra, R.K. (2019). Gandhi and Hinduism. Indian Journal of Public Administration 65(1) pp. 71–90. Retrieved October 30, 2020, from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0019556118820453

- Heredia, R. (2009). Gandhi’s Hinduism and Savarkar’s Hindutva, p.65

- Mishra, R.K. (2019). Gandhi and Hinduism. Indian Journal of Public Administration. P. 75

- Iyer, R. (1986). The moral and political writings of Mahatma Gandhi (8 Vols.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press

- Gandhi, M.K. Collected Works, 1958-89 (100 Vols.). Government of India, New Delhi.

- Ibid.

- Jaffrelot, C. (2005). Dr Ambedkar and Untouchability. London: Hurst.

- Gandhi, M.K. Collected Works, 1958-89. Vol. 67 pp. 153-154

- Jordens, J. T. F. (1998). Gandhi’s religion: A homespun shawl. New Delhi: Palgrave Macmillan.

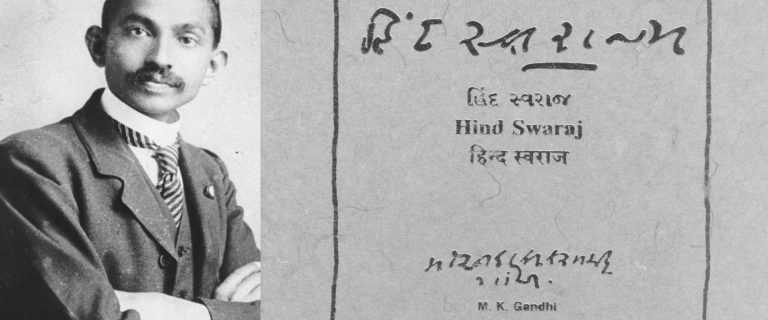

Featured Image Credits: dailyo.in