When Law is just a Punchline: Urgent Need to reclaim POSH

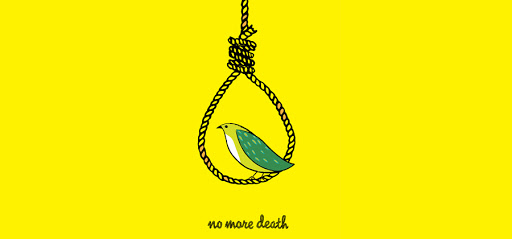

Recently, Fakir Mohan College in Balasore district, Odisha, was in the national news. A 20 year old B.Ed student from the college alleged that the Head of the Education Department had been sexually harassing her and threatening to fail her if she refused his advances. As per reports of her multiple complaints from the girl, no action was taken by the college authorities. Instead, she was allegedly pressured from college administrations to stay silent. In protest, on July 12, she set herself on fire in front of the principal’s office and later succumbed to her injuries. This horrifying act speaks volumes. After the incident, the major policy gap highlighted was the poor implementation of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 (POSH Act). In response, the Government of Odisha issued a directive to all higher education institutions in the state to immediately constitute and operationalize Internal Complaints Committees (ICCs) as mandated under the ACT.

Through this article, I want to shed light on the fact that while the formation of ICCs is necessary, it alone will not solve the issue of sexual harassment in workplaces or educational institutes. My professional journey through different sectors (government, social and corporate) gave me exposure to POSH implementation in these spaces. The gap between what’s written in policy and what plays out on the ground is stark; a troubling pattern of POSH being reduced to a tick-box compliance exercise and a matter of joke. This disconnect is not just visible in institutional setups but also in everyday workplace interactions where casual jokes and misplaced fears reveal just how misunderstood the POSH, Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act, 2013 truly is.

I remember a moment during a lunch break dining table conversation at work. A male and a female colleague were engaged in friendly banter over sharing lunch. At one point, the female colleague joked, “I won’t share the dessert with you.” Before the other colleague could respond, another male colleague suddenly remarked, “Don’t say anything to her, or she will file a POSH complaint against you.” Everyone at the table smiled, while the female colleague looked visibly awkward. I sat there wondering that how could a light-hearted exchange over dessert so casually be linked to a POSH complaint?

Similarly, at another instance I heard a male colleague mentioning POSH out of context when a female colleague casually patted a male colleague back and male colleague jokingly said, “I can’t PAT your back otherwise you will file a case under POSH”. The woman was visibly taken aback. These were not merely joke about POSH but signs of a deeper problem that how POSH and sexual harassment is being misunderstood, misused in humor, and often mocked. And it’s not limited to conversation at office spaces but social media is filled with funny memes and reels mocking the POSH while the actual awareness on POSH is lacking in majority.

What is worrying is that all the colleagues present in both the instances had gone through the mandatory POSH training conducted by the employer. Yet, they either lacked a clear understanding of what constitutes sexual harassment or pretended not to understand. Although the ways the companies/organizations conduct POSH training there are high chances that employees have half backed knowledge on the ACT. Because many organizations conduct these trainings through pre-recorded online videos. These formats neither offer employees the space to clarify their doubts nor the comfort to express their own insecurities or confusions.

POSH is not just about knowing the definitions of what counts as harassment. It’s about creating safe, inclusive spaces for women to work and speak freely. Unless ICC members carry a strong gender lens and a genuine sensitivity to power dynamics, these laws remain meaningless on the ground. For POSH to work, organizations need to make sure that the ICC members are not just names on paper. They need to be trained well, sensitized, and selected carefully. This is not a one-time training job. It needs to be continuous, intentional, and supported by leadership. Otherwise, the risk is high that the people in power like the FM College, Balasore’s principals who allegedly not only ignored the student’s complaint but threatened her might become an ICC member. The law then becomes an enabler of silence instead of a protector of dignity.

As an ex-member of an Internal Complaint Committee (ICC), I have witnessed closely the many emotional layers a woman goes through before and after filing a complaint. It is not as simple as reporting and moving on. There is fear, there is hesitation, and above all—there’s guilt. Guilt for “ruining someone’s career,” guilt for “creating a scene,” guilt for not speaking up earlier. Many women even ask themselves, “Did I overreact?” or “Will they believe me? And now, when POSH is being reduced to a joke in so many workplaces, this hesitation only grows. The doubt creeps in deeper.

While sensitization of ICC members can make the redressal of sexual harassment more Just but it can’t ensure prevention of sexual harassment at the workplace. The reality is, most of our educational institutions and workplaces and powerful positions are heavily male-dominated. Skewed gender ratios are often normalized and rarely questioned. Creating a truly safe environment for women requires more than POSH. It needs more women in leadership roles. Representation may not guarantee change, but it gives women the psychological confidence to speak up. And when a sexual predator holds power, numbers matter. Presence matters. And so does the politics of who gets to sit at the decision-making table.

I recall a POSH session in a social sector organization when; I said that some male colleagues seem to be afraid of POSH. One colleague responded, “Then how can we create a comfortable environment? Are women being deprived of opportunities because men are scared?”

I didn’t have to answer, a male colleague did. He said, “If a man is afraid of POSH, let him be. If his intentions are wrong, he should be afraid. And if they’re not, there’s nothing to fear. And if he has doubts about POSH, he should take the initiative to understand the Act better.”

His words stayed with me. Because that’s the mindset shift we need. The formation of ICCs is a necessary first step but it cannot be the last. POSH awareness cannot remain a mechanical, compliance-based checklist. What we need is continuous sensitization, leadership support, and a cultural transformation—one that doesn’t silence women for speaking up, but instead listens, believes, and stands by them.

References

- Mishra, Ashutosh. 2025. “Protests In Odisha After Sexual Abuse Survivor Sets Herself Ablaze on Campus.” The Wire, July 13, 2025. https://thewire.in/rights/protests-odisha-balasore-sexual-harassment-self-immolation.

- “Balasore Incident: Odisha Govt Directs DEOs to Enforce ICC Formation, Ensure Safe Environment in Schools,” 2025

- “THE SEXUAL HARASSMENT OF WOMEN AT WORKPLACE (PREVENTION, PROHIBITION AND REDRESSAL) ACT, 2013” 2021