Friends, enemies, and populist politicians

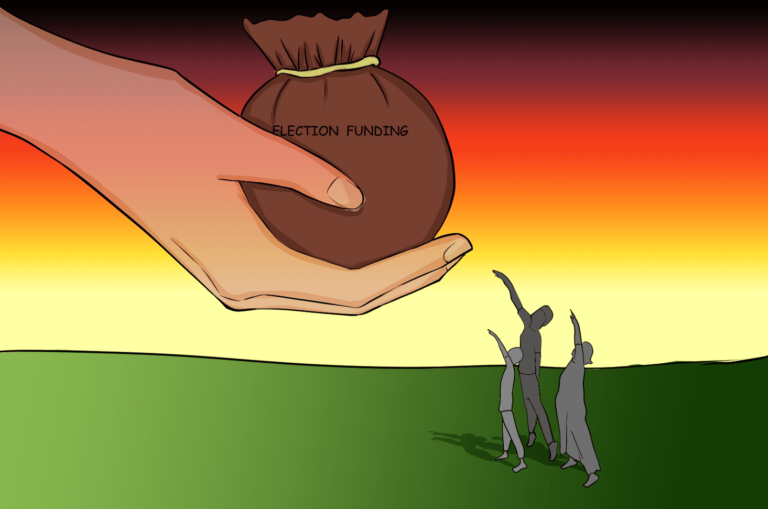

The 20th-century politics majorly revolved around one question: How do we organize modern states? The same question in the 21st century poses a dilemma with regards to the democracies. Towards the end of the last century, liberal democracy triumphed over Fascism and Communism. The rise of populist leaders today marks a dangerous advent towards which the liberal democracies seemed to float, often highlighting the conflict within itself. Totalitarian Regimes in the 20th century reveal a trend that seems to be in conjunction with practices of the populist leaders today who are slowly pushing the democracies towards an inevitable implosion. Thus, to understand why democracies collapse from within, it is pertinent that a brief focus must be put upon the political practices of the leaders today, and of the nature of the State, and juxtapose it with history to find identifiable characteristics that reveal this trend.

Historical analysis of totalitarian regimes reveals the paradoxical nature of its politics, revealing what Historian Richard Hofstadter called the ‘Paranoid Style of Politics’. In this style of politics, the truth of the statement issued by any politician is at best secondary to the paranoia mobilized by it. There is a visible consistent effort to identify an ‘enemy’ by employing conspiratorial rhetoric, to the extent that politics itself becomes inherently conspiratorial: that the only ‘truth’ which remains of politics is to eliminate the enemy/opposition. For a paranoid leader, his nation is both the boldest and the weakest, his nation is the most righteous, yet the falsity of even minimal extent is fatal to its existence, and therefore, the identification of the ‘enemy’ takes primacy, whether real or fake, to mandate extra-legal access to eliminate the opposition from within.

The tenacity with which regimes ‘create’ perceived external enemies to neutralize any opposition from within is truly a measure of totalitarian dictatorship, and the genius of a dictator. The intellectual foundations to such politics can be traced back to the works of a prominent Nazi Jurist Carl Schmidt, who laid down the legal foundations of the Nazi Regime. In his most famous work ‘The Concept of Political’, he works to determine the essence of the ‘political’ – a domain upon which every other domain (Economic, Social, Religion etc) is based – and argues that it influences other spheres precisely because of its capacity to distinguish between the friend and the enemy. The element of the ‘political’ which can perform this function inevitably becomes the State, with its capacity to identify existential threats to itself, and Schmidt believed that strong leaders could not just thrive on the rhetoric of friend and foe, but that the very essence of ‘political’ is determined by the ability to detect such a foe. He called this the ‘State of exception’.

To invoke this ‘State of exception’ is not necessary to just identify ‘external’, but ‘internal’ threats and it works on a simple logic: The real threat can only be combated once the internal ones are rooted out. History is ripe with such examples, and in the Nazi regime, it took the form of the ‘Jew’. The State of exception was vital to the process of systematic vilification and exclusion of Jews because in the pursuit of its internal enemies Nazi regime could convince itself of its own necessity. This is why an Italian scholar, Giorgio Agamben, defined totalitarian dictatorships as the “establishment, by means of State of exception, of legal civil war, that allows for the elimination of not only political adversaries but an entire category of citizens who for some reason cannot be integrated into our political system”. Thus, Hitler came into power and signed a ‘Decree for Protection of People and the State’ while suspending provisional and personal liberties of all the German citizens.

Today’s circumstances reveal precisely this nature of the State where “the idea of the foreigner, the outsider, and the enemy can be translated into any one-size-fits-all form of authoritarianism, in which one’s ‘love of country’ becomes determined by the extent to which one follows the leader in his paranoid pursuit”. It also prompts us to reflect on the extent of control that is out-sourced to the state and its apparatus, to what extent the State claims its moral high ground in matters that concern people, and more importantly, the need to have something ‘external’, like a state, take over the responsibility of controlling the actions of the self and others. To outsource the responsibility of controlling the self and the people to the State apparatus and a populist figure is a slippery slope that will lead to a greater catastrophe. It is, therefore, ignorance on the part of those who support it blindly during the times of conflict, especially when it poses itself as the highest moral actor.

The State comprises people and has no independent existence of its own. It is paradoxical that people created it themselves and gave it the power in turn to exercise power and control over them. However, when the objective of the state is to legitimise its own existence, as an institution, it doesn’t take into consideration the people for whom it exists, but, like a self-fulfilling prophecy exists for itself. In the instances where it professed ultimate claim to righteousness and constantly looked out for a perceived ‘enemy’, it became totalitarian in nature. Nazi Germany and Stalinist USSR stand as primary examples of the states that have, on the pretext of self-preservation, suppressed people to their deaths.

The current state of affairs offer ample evidence of paranoia actively spearheaded by the populist leaders. There is a permanence of a coherent narrative bereft of factuality and a permanent state of conflict: whether it’s the ‘murderous gangs from the South’ as Trump calls it or the terror from the ‘Jihadists’ as the factions from extreme right name it, there seems to be a perpetual enemy that is created to justify the presence of a paranoid leader and to invoke the State of exception. This leaves no choice but for voters and citizens to recognize these threats and distinguish the real ones from fake, because after-all democracies are like sand-castles on the shore. They are easy to crumble with tremendous mobilization of paranoia as it happened in Germany in 1933. The dangerous revelations in the politics and policies of the populist leaders must always be dealt with prudence and therefore, the biggest challenge today in the realm of politics becomes about how organizing modern states must be relooked within the context of liberal democracies.

Featured Image Credits: Wikimedia

I completely agree with the author but liberal democracies are becoming totalitarian.