‘1Q84’ is a Surrealist Advocate of Dissent

Abhijato Sensarma is from Kolkata, India. His works have been published in The Wire, The Quint, Scroll.in, ESPNCricinfo and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency among other publications.

Haruki Murakami’s 1Q84 is one of the most bewildering works in world literature. It is also a homage to the postmodern world without succumbing to its wilder impulses. As a standalone novel, it revels in the exploration of morality, reality, and the power of love.

Magical realism as a setting for romance

It is difficult to summarise this novel. As a matter of fact, the very act of Murakami penning down these three volumes is an exploration of magical surrealism as a genre.

Most of the book’s thousand pages or so are spent covering its two protagonists – Aomame and Tengo. After sharing a brief moment of passion during their childhoods, they traversed their separate ways in life.

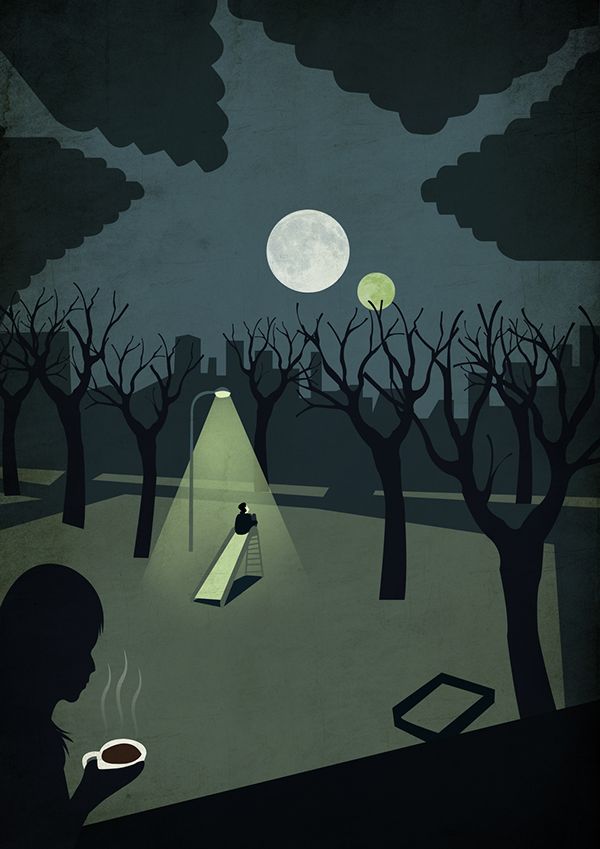

In the years to come, they slowly realise that this encounter has left them longing for more. But fate and reluctance keep them apart, until they are pulled into a world with two moons. This fictionalised version of the year 1984 is referred to as the titular ‘1Q84’.

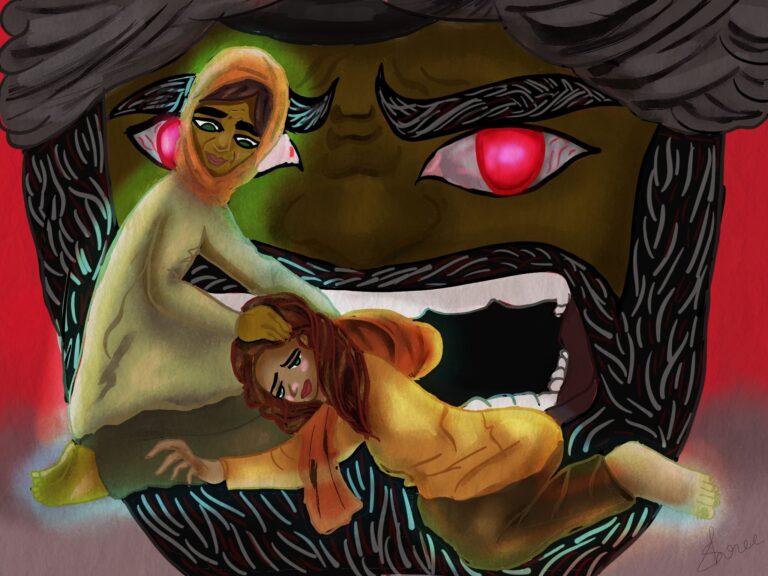

It is also inhabited by mysterious beings called the Little People, who transcend the limits of modern morality by amalgamating themselves with a cult called Sakigake to influence the happenings of this world.

Murakami is a master of constructing surreal narratives. His prose often bewilders readers, but 1Q84 has been hailed as his magnum opus in the years since its publication because of the passion that forms its backbone. The heart of the story remains the love between Tengo and Aomame. Ironically, this unruliest emotion known to mankind provides a semblance of order to the novel’s chaotic worlds.

Resistance to authority

Murakami’s philosophies remain understated even as they filter into all his works. His affinity for subtle dissent plays a major role in the plot of 1Q84.

He has always been against institutional religions. This novel still portrays the figures of authority as alien entities and a hindrance to the efforts of Aomame and Tengo. But the story offers them the benefit of ambiguity that postmodern works specialise in, especially because the protagonists themselves engage in immoral activities throughout the novel.

Aomame is a part-time assassin, who murders abusive husbands thriving in a patriarchal society without any repercussions for their breaches of the law. Murakami knows these same laws were designed with the intention of optimising this world for the men living in it. So, it is only appropriate that his depiction of Aomame as a woman with a confused sense of morality in a man’s world is a feminist masterclass.

While Tengo seems less rebellious, he too harbours traits that lie dormant, but are dangerous to those who demand compliance. He inhabits a world of his own, which he starts calling the ‘Town of Cats’ (read the story here). It soon becomes a physical manifestation when he gets transported into this reality – the reality of ‘1Q84’. This happens because his traits finally influence him to venture into the territory of moral ambiguity.

He secretly rewrites a novel called Air Chrysalis, originally composed by a 17-year-old girl named Fuka-Eri. Even this is an act of dissent against the norms of society. The transportation of both protagonists into this new world acts as a gateway for their eventual discovery of each other.

In Murakami’s world, dissent is an invaluable tool for revealing the nuances that remain hidden under the tarp of daily existence – be it the ‘invisible hands’ of authorities, the power of true love, or the inexplicability of a second moon floating in the night sky.

Writing a novel within a novel

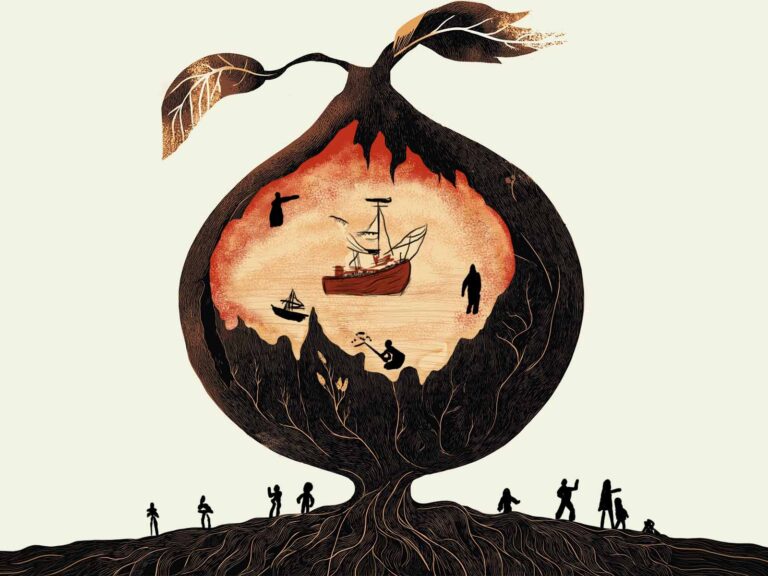

The book Air Chrysalis acts as a metaphysical MacGuffin for the most part. It incites changes in the lives of the characters involved in its writing, but it is only around the halfway point of the story that we are given a comprehensive glimpse into its actual plot.

In many ways, the novel is a representation of Murakami’s writing career. He is a recluse in Japanese literary circles, like the author Fuka-Eri, preferring his reclusiveness to becoming a part of the ‘establishment’. The novel is aligned with the genre of 1Q84, which is only fitting considering the meta-narrative commentary it presents about the polarising opinions most critics have about Murakami’s writing.

It has the lowest approval rating amongst his full-length books according to iDreamBooks, but has been simultaneously voted by the reputed Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun to be the best novel published during the Heisei Era (1989-2018).

Reading a novel as dense as 1Q84 connects the author and his readers in a manner similar to the relationship of Aomame and Tengo, even if the former bond is more platonic than the latter’s. Being immersed in the surrealist fiction of Murakami is like being immersed in the world of 1Q84, just in a different sense of the word. Once there, one can only marvel at the truths of life never noticed before.

Simple prose as a model of elegance

Murakami adheres to a Hemingwayesque style of writing. His translators do an excellent job of rendering the novel suitable for English readers, but his unique style seeps through the language barrier. The mystifying elegance of his works is largely down to the simplistic way in which he deals with his subject matter while composing his prose.

The novel, at times, is weighed down by frequently repeated exposition, and ill-timed inner monologues. This confuses the pacing of the novel. While it largely revels in its endeavours, it also tries to be a postmodern thriller with only moderate success.

Readers familiar with Murakami will know that his novels are best devoured slowly, by taking in every clever metaphor and processing the sentimental beats of the story while giving them the time it deserves. So, while the novel is a page-turner in its own right, the readers’ journey can be occasionally frustrating, as is the norm for novels of this length.

Some critics have also noted the dialogue-writing as a point of weakness for the novel, but if readers acclimatise themselves to the tone of the novel, the exchanges between the ensemble of characters turn into an enjoyable experience that contributes to the unorthodox narrative style of the author.

The philosophy of fate

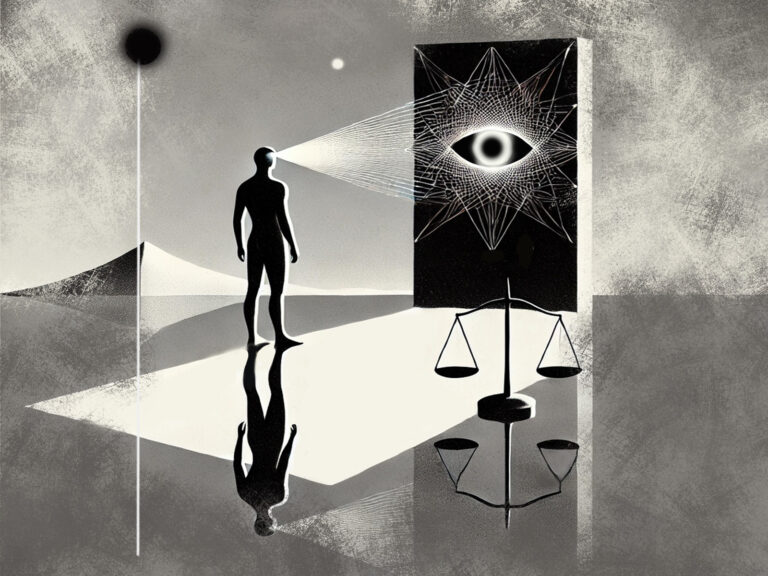

The novel can also be seen as a meditation on the many trivialities of fate. The Little People and the telekinetic ‘voice’ they use to communicate with the people of Sakigake act as a representation of fate used as a tool by authorities, which can be likened to the character of ‘Big Brother’ in the classic Orwell novel, 1984.

Once more, Murakami attributes the qualities of fate to not only the metaphysical forces of nature, but with the humans who carry out their ‘commands’. Fate is not an indecipherable component of life. Rather, it is an extension of the actions carried out around us, especially by those who claim to be the representatives of divine intervention.

Aomame is brought into 1Q84 against her will. Even Tengo is an unwitting passenger on the metaphorical train that ‘switched tracks’ at some point in time to carry them into the ‘Town of Cats’. The Leader of Sakigake, who is the primary Receiver of the ‘voice’, says that it is the will of the Little People to bring them into this world. There is no escape from it, even though it can be realigned to a certain extent if compromised.

Challenging the certainties of world order

The final third of the novel sees a shift of philosophy for both Aomame and the readers, who conclude that fate is more malleable than its representatives claim it is. When she ventures out into the unknown to finally get in touch with Tengo, she displays her free will influencing her to break out of the cycle of desperation and helplessness the modern world has acclimatised us to.

At the end of the novel, Aomame and Tengo eventually find each other and escape to a new world. It is dissimilar from the one they started in, but it is also different from the world fate had apparently banished them to for the rest of their lives.

As expected, Murakami ends the novel with ambiguity and unanswered questions. But tempered expectations from the plot itself gives rise to the realisation that he has given us vital answers to many of the conundrums presented to the readers during the progress of the novel.

Optimism in the face of uncertainty

By allowing Aomame and Tengo to escape the clutches of fate and the Little People – even if their new world is brimming with uncertainties of its own – Murakami advocates for the persistence of faith, even in the face of fate.

There can never truly be an ‘escape’ from the worlds we create for ourselves, and perhaps, it is fate that controls our exercise of free will as well. But when we write, read, and think, we are collaborating with our metaphysical overlords to bargain for a better future. It might be just as uncertain and unpleasant as what they originally had in store for us, but at least, this future is one we can claim to be ours.

1Q84, in the end, turns out to be a perfect manifestation of this perennial compromise between the dissenting artist and the all-powerful establishment. The result of this bargain might seem inconsequential in the grander scheme of things. But the existence of Air Chrysalis proves that every piece of art is one created against the odds, and possesses the potential to alter the world in ways we never thought it could.

Image Credit: “1Q84” by Benedetto Cristofani